Statistics in context

Last updated: 27 September 2024

What the evidence below shows is that a significantly disproportionate number of people from certain racialised communities are affected by police operations and practices such as stop and search and racial profiling (the use of race, ethnicity, religion or national identity as grounds for suspecting someone of having committed an offence). Disproportionality also extends to the use of force, strip-searches, arrests, fines (particularly during Covid 19), charging, sentencing and imprisonment. It is important to note that disproportionality in crime statistics does not mean that certain people or groups are more criminally-inclined than others, but rather, that there is a whole process at work – from bias within the criminal justice system, to societal issues such as bad housing, school exclusion, poverty, precarious employment – which stacks the odds against some people.

In March 2023, the Baroness Casey Review of the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the Metropolitan police, commissioned in the wake of the kidnapping, rape and murder of Sarah Everard by a serving police officer, found institutional racism, homophobia and misogyny across the force. While police chiefs have acknowledged extreme racist (as well as misogynistic) attitudes amongst serving police officers, and will acknowledge ‘systemic failings’ and ‘bias’, the fact that the entire criminal justice system may be acting structurally in ways that discriminate against BME communities is contested. Yet the evidence does point to institutional racism, not just in the police but in the criminal justice system as a whole – which would include prosecution, determinations, sentencing, prisons and other forms of custody.

Structural racism can be reinforced by a perception (or call it prejudice, stereotype, stigmatisation) within rank-and-file police, as in much of society and compounded by parts of the media, that certain groups present a problem and therefore require particular surveillance and treatment. This could be because of the colour of their skin, their religion, migration status, or because they do not have regular work, identify with particular music genres, live in certain areas or estates, or are believed to have been involved in ‘gangs’. They have been constructed by society as a ‘social problem’.

Not just the police, but prosecuting agencies, magistrates, judges, lawyers, prison officers and probation services can also engage in negative stereotyping about particular BME groups. A survey of 373 legal professionals found that 56% had witnessed at least one judge acting in a racially biased way, with 52% witnessing discrimination in judicial decision-making, most frequently directed towards Asians and black people – lawyers, witnesses and defendants. In addition, these institutions are not diverse, ie, do not reflect the total population. The workers within them will be unlikely to have the same lived racial and class experience as defendants. For example, in 2019 92.6% of judges in England and Wales were white and 7.4% were from a BME background. In 2020, 92.7% of police officers were white and 7.3% were from BME backgrounds. And in 2022, 91.9% of officers were white, and 8.1% identified as belonging to a minority ethnic group. In addition, BME staff within these organisations also experience stereotyping and discrimination. Baroness Casey’s review found that black officers were 81% more likely to face disciplinary action and new ethnic recruits over 120% more likely to be served with a Regulation 13 (‘unsuitable for policing’) notice than their white counterparts. Many black prison staff who participated in a survey carried out by HM Inspectorate of Prisons said they experienced discrimination that hindered their career profession, adding that they were viewed by colleagues with the same suspicion that affected black prisoners and worried about being accused of collusion or corruption.

But the context is larger than institutions being ‘white’ and individuals being prejudiced. We live in what is known as a neoliberal society (characterised by privatisation, deregulation and cuts in government spending), as opposed to a social welfare society (where the state prioritises the provision of public services and acts against inequalities). Services that used to be there to help and protect young people and marginalised groups have been axed. As austerity bites, policing (including by private security companies) is used to manage the fall-out in society.

THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

The UK has three separate criminal justice systems (England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland), and most of the statistics referred to in this section relate to England and Wales. The criminal justice system and legal jurisdiction of England and Wales are reserved – non-devolved – matters, controlled by the UK parliament and government at Westminster. The criminal justice systems of Scotland and Northern Ireland are devolved to the Scottish parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly respectively. Devolution powers differ, but certain powers relating to criminal justice, including those relating to counter-terrorism, firearms, extradition, misuse of drugs and human rights safeguards, remain reserved to Westminster for all devolved legislatures.

Despite the differences, as well as the larger BME population in England and Wales, what is important to note is a common experience of the criminal justice system, where black and minority ethnic communities (BME) are overrepresented at almost all stages of the criminal justice process, disproportionately targeted by the police, more likely to be imprisoned and receive longer sentences than white people.

Labour MP David Lammy’s research into racial disproportionality in the criminal justice system in England and Wales in 2017 (‘the Lammy Review’) revealed, among other things, that a majority of BME people (51%) believe the criminal justice system discriminates against particular groups and individuals, compared with 35% of the British-born white population. This lack of trust starts with policing, but has ripple effects throughout the system, from plea decisions to behaviour in prisons.

POLICING

Stop and search

Researchers have linked these lower levels of trust in the police amongst BME communities to the fact that people from these communities are far more likely to be stopped and searched than white British people. Only 35% of black Caribbean people interviewed for a 2022 survey that focussed on experiences of stop and search expressed confidence in the police, compared to 49% of those interviewed across all ethnicities, and 64% of white people. In addition, the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC), citing the case of a child who was stopped and searched 60 times in two years, has suggested that research into the ‘trauma’ of stop and search may be needed, and that black people need ‘protecting’ from stereotyping and racial bias.

There are a number of key powers the police in England and Wales can invoke to stop and search an individual that emerge in different statutes, with some crossover in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence (PACE) Act 1984 (and associated legislation including section 23 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and section 47 of the Firearms Act 1968) allows the police to stop and search someone they think may be carrying items like stolen property, drugs or firearms.

Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order (CJPO) Act 1994 allows the police to stop and search anyone (‘suspicionless’ stop and searches) within an area designated by a senior officer where it is believed serious violence may take place, for up to 24 hours, to prevent violence involving weapons. [1]

Section 43 of the Terrorism Act (TACT) 2000 allows the police to stop and search any person they ‘reasonably suspect’ of being a terrorist, in order to determine whether that person has in their possession any item that could ‘constitute evidence’ that they are a terrorist.

Section 47A of the Terrorism Act 2000 enables a senior police officer to authorise ‘suspicionless’ stop and searches within a specified area where an act of terrorism is believed to be likely, for a limited time, up to a maximum of 14 days.

Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000 allows a police officer, an immigration officer, or a customs official to stop, search, and detain any person crossing the UK border (for example, at an airport or port) for up to 6 hours in order to determine whether they are a terrorist. Section 7 powers were further expanded under section 78 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 to allow officers to stop small boat arrivals. [2]

Section 165 of the Police Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 allows police to carry out suspicionless stop and search on adults convicted of knife or offensive weapons offences (whether as a principal or on a joint enterprise basis) who have been made subject to Serious Violence Protection Orders under the section.

Stop & Search in England and Wales

Between April 2019 and March 2021, government data show that in England and Wales there were 52.6 stop and searches for every 1,000 black people, compared to 7.5 for every 1,000 white people. However, the figure for black people is likely to be a gross underrepresentation. For black people who do not identify or have been misidentified as either black Caribbean or black African, and labelled ‘black other’, their stop and search rate was 158 stop and searches for every 1,000 black people, the highest rate overall. In addition, there were 17.5 stop and searches per 1,000 people with mixed ethnicity, and 17.8 per 1,000 Asian people in England and Wales.

In 2021, according to Stopwatch, black people were nine times more likely to be stopped and searched under section 1 of PACE for suspected drug possession despite using drugs at a lower rate than white people. The figures show a marked increase in the ten years since 2011, when black people were six times more likely to be searched for drugs. Government data show that 99% of all stop and searches in England and Wales were under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE). In addition, 1,750 section 60 stop and searches involved black people (19.2% of all such stops), and 2,561 section 60 stop and searches involved people with unknown ethnicity (28.1% of all such stops).

Dyfed–Powys Police (Welsh: Heddlu Dyfed–Powys) is the territorial police force in Wales that covers Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire. Data released by the Dyfed-Powys Police and Crime Commissioner records a 240% increase in stop and search during 2022/23, of which 71 per cent were conducted under Section 23 of the Misuse of Drugs Act. Sixteen per cent of drug related stops led to arrests.

There were no stop and searches under section 47A of the Terrorism Act between 2019 and 2021 in England and Wales (unlike in 2017-2018, where there were 149 stop and searches under that section).

Stop & Search in Scotland

Police Scotland has recorded some information on stop and search by ethnicity in its annual report. The Scottish Information Commissioner has intervened to ensure a more robust approach to data takes place. Following FOI requests, Police Scotland revealed in December 2022 that people from minority ethnic backgrounds are up to 20 times more likely to be stopped under Schedule 7 counterterrorism powers, of 1,371 passengers intercepted at Scottish ports and airports during peak travel months from 2016 to 2021.

Stop & Search in London

It is important to note that in London, the most ethnically diverse region of the UK, the Metropolitan Police routinely conduct more stop and searches than anywhere else in England and Wales. In the year ending March 2021, the Metropolitan Police in London made almost half (45%) of all stop and searches in England and Wales. There were 69.5 stop and searches for every 1,000 black people in London, compared with 28.8 per 1,000 black people in the rest of England and Wales. London had the highest rates for all ethnic groups except for the mixed and white ethnic groups (where the rates were highest in Merseyside). In the year to January 2023, Met police figures show that BME people accounted for five-eighths of stops, and over one-third of all stops were of black people. Furthermore, research commissioned by the London mayor’s office as part of its race action plan found that black people were seven times more likely than white people to be stopped by police on suspicion of carrying weapons, a higher racial disproportionality than for general stop and search.

This disproportionality carries through into ‘more thorough searches, intimate parts exposed’ (MTIPS), which are effectively strip searches of a person who is not under arrest. A February 2023 report showed that in the three months since the death of Chris Kaba in September 2022, black people accounted for 46% of these searches, down from 55% but still highly disproportionate to their 13.5% share of the London population. White people accounted for 31% of MTIPS, up from 26% (share of population 54%); while Asians made up 16% of such searches (share of population 20.7%).

Effectiveness of Stop & Search

Stop and search practices are largely ineffective. Between 2020 and 2021, the Home Office found that in 77% of stop and searches across England and Wales, the outcome was recorded as needing ‘no further action’.

Strip searches and young people

Under stop and search powers, police can also conduct strip searches which, alongside intimate body searches, are one of the most intrusive powers at the police’s disposal. While 95% of strip searches in 28 police forces in England and Wales in 2022 were carried out against adults, 5% involved children. In 2021, the Metropolitan Police carried out 269 More Thorough Searches that expose Intimate Parts (MTIPS) on children.

In 2022, a Home Office study found that 87% of all strip searches (irrespective of ethnicity) were of males, and 19 per cent of adults strip-searched were black. Of the 3,000 children strip-searched in that year, just over one third (1,096) were black. Greater Manchester Police, South Yorkshire, Surrey, Sussex and Thames Valley were among the 15 police forces that did not provide data. Furthermore, data from 41 out of 43 police forces for the year ending 31 March 2023 shows that more than 60 children are being strip-searched a week and children of Black, Asian or mixed-race descent are more likely to be targeted for strip searches. While some forces fail to record the ethnicity of strip-searched children, available data shows that 45 percent of all affected children had their ethnic background recorded as white.

The strip-searching of children came into the national spotlight following the case of Child Q, a 15-year-old black student at an east London school, who was strip-searched by police officers in 2020 during her period after her school called the police, saying that she smelt of cannabis. The scandal surrounding her case, which came to public attention in 2022, has also led to a discussion about the ‘adultification’ of black children. As a result, the Children’s Commissioner carried out a review which revealed that black children are 11 times more likely to be strip-searched in England and Wales than white children. Between 2018 and 2022, there were at least 2,847 pre-arrest recorded child strip-searches, 38% involving black children. Police did not follow the rules in more than half the cases, and in half of all searches nothing was found. Appropriate adults were not present in 52% of cases.

Liberty Investigates has also conducted its own data analysis. Using Freedom of Information requests it found that 47% of girls subjected to strip-searches by the Met between 2021 and 2022 were black. Black girls were almost three times more likely than their white counterparts to be subjected to the most invasive form of strip search in which their intimate parts were exposed. 75% of these strip searches resulted in no further action.

Police in Schools

The case of Child Q has opened up a discussion about police in schools. The role of school police officers (termed ‘safer schools officers’ or SSOs) ranges from being a point of contact for teachers to more intensive interventions such as stop and search and surveillance of children suspected of being gang members. The Runnymede Trust found in 2022 that police officers operating within UK schools (a total of 979) are based most often in schools in areas with higher numbers of pupils eligible for free school meals, correlating with higher numbers of black and minority ethnic students.

Data-driven surveillance, racial profiling and policing of black music-genres

While artificial intelligence, automated-decision and risk-management systems, which rely on data harvesting and network mapping, are integral to modern criminal justice systems, there is no guarantee that such technologies do not reproduce and reinforce discrimination.

The Metropolitan police’s Gangs Matrix, set up after the 2011 ‘riots’, is a database of people in London whom the police consider to be ‘gang nominals’ or suspects and aims to address serious youth violence. But it has been accused of reflecting racial and cultural stereotypes about young black men, their family, their associations, and the type of music they enjoy. In 2017, Amnesty International found that 78% of those listed on the Gangs Matrix were black, with the youngest 12 years old, and 85.6 % were from racialised minorities, while just 27% of those convicted of offences related to serious youth violence are black.

In November 2022, the Metropolitan police conceded, under threat of legal challenge, that black people were disproportionately represented on its Gangs Matrix and that the database as constituted was unlawful, and over 1,000 names – nearly two-thirds of those entered – were removed from it.

Another Metropolitan police initiative, Project Alpha, which targets serious violence and gangs through online surveillance of drill music content and other videos, is also causing concern that it is linked to racial profiling. FOI requests reveal that it has led to the harvesting of the personal data of children as young as 13, possibly younger. The University of Manchester’s Prosecuting Rap project has identified more than 70 trials from 2020 to 2023 in which rap evidence was used by police and prosecutors, with almost half recorded cases featuring defendants under the age of 18. Art Not Evidence, a coalition of lawyers, journalists, artists, academics, youth workers, human rights campaigners and music industry professionals, campaigns for the decriminalisation of rap music and creative expression more broadly. It reports that at least 240 people have been prosecuted, at least in part, on the basis of their taste in music.

The Metropolitan police’s Risk Assessment Form 696, introduced in 21 boroughs in London in 2005, allowed police to shut down music events that featured DJs or MCs. Black artists complained that between 2008 and 2017 the measure was disproportionately used against events featuring grime artists or catering to predominantly black audiences. The actions of campaigners helped to ensure that Form 696 was scrapped in 2017 and replaced by a ‘voluntary partnership approach’ for venues and promoters, though the voluntary nature of this approach has been questioned.

However, the issue resurfaced again during the Covid lockdown, when more than a third of 441 lockdown fines in England and Wales for ‘amplified music’ events between March 2020 and July 2021 were issued to black, Asian and mixed-race people. National Police Chiefs Council statistics show that the Met was responsible for issuing 203 of these fines, by far the largest number of any individual police force.

Policing of protest

Examples such as these which suggest that black events are targeted by police, also extend to the policing of protest where demonstrations linked to the concerns of racialised communities are over-policed. A FOI request by Liberty Investigates revealed that the only events for which Metropolitan police chiefs authorised the potential use of baton rounds were black-led gatherings, approving the use of plastic bullets at each Notting Hill carnival since 2017 as well as Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. Plastic (and rubber) bullets were previously used in Northern Ireland where they caused 17 deaths.

In addition, since October 2023, the police have used sections 12 and 14 of the 1986 Public Order Act to harry the organisers of pro-Palestinian solidarity demonstrations by placing an ever-expanding number of conditions and penalties against them. Further FOI requests by Liberty Investigates reveal that the National Police Chiefs’ Council assessed the threat of violence from far-right protests as ‘minimal’, whilst seeing pro-Palestinian and environmental movements as potentially threatening public order.

ARRESTS

There were 646,292 arrests carried out by territorial police forces in England and Wales between April 2020 and March 2021. The Metropolitan Police accounted for the greatest number of these arrests (17%). Following the pattern of previous years, persons who identify as black or black British were arrested at a rate over three times higher than those who identified themselves as white; mixed and ‘other’ ethnicities were arrested at a rate around 2 times higher, and people who identified as Asian or Asian British were arrested at a rate 1.2 times higher.

In London, 55% of people arrested by the Metropolitan Police were from the Asian, black, mixed and ‘other’ ethnic groups combined – the highest percentage of all police force areas across England and Wales.

Not guilty by association

According to the campaigning organisation Joint Enterprise – Not Guilty by Association (JENGbA), the joint enterprise doctrine (whereby people can be arrested and convicted of an offence, despite not having committed it, if they intended to encourage or assist in it) is disproportionately used against BME communities. Many joint enterprise arrests (and subsequent prosecutions) rest on the idea that young people are part of a ’gang’.

Use of force and restraint

The persistence of racial stereotyping of BME people is also reflected in statistics on the disproportionate use of force, including excessive handcuffing of young black men and children, the use of spit hoods, pepper spray, Tasers (introduced in 2003) and other lethal weaponry. One-third of the 114 children restrained using spit hoods in England in the first nine months of 2018, were black or from other minority ethnic groups. Experimental Home Office statistics 2019/20 indicate that black people are 5.7 times more likely that white people to have force used against them and 8 times more likely to be ‘compliant handcuffed’. A February 2023 report by INQUEST revealed that black people in Britain are seven times more likely than white people to die following restraint by police.

Disproportionality between black people and white people is markedly higher when the police use high-degree force, such as Tasers and firearms, compared to low-degree force. In 2022, the National Police Chiefs Council announced an independent review into racially disproportionate Taser usage. Across England and Wales, black people are 7.7 times more likely to have Tasers deployed against them compared to white people, an analysis of data found. In relation to minors, statistics for 2018 show that 74 percent of Taser deployments in London were of people from BME backgrounds, with 50 per cent of the 839 children on whom Tasers were used were black.

Drug offences

Black, Asian and minority ethnic people are more likely to be arrested for drug offences compared to white people, with Stopwatch concluding that cannabis laws criminalise the black community at disproportionate rates. In 2016, the Ministry of Justice (according to the Lammy review) found that for drug offences, the odds of receiving a prison sentence were around 240% higher for BME offenders, compared to white offenders. The government reported in 2020 that in 2018-19, just 8% of white suspects were arrested for drug offences compared to 19% of black, 15% of Asian, 15% of mixed ethnicity and 12% of Chinese or other ethnicity suspects.

CHARGING AND PROSECUTION

Police make the decision to prosecute less serious offences, which account for two-thirds of cases, and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) decide in the more serious cases. In 2019, the Ministry of Justice found that 23% of prosecutions were of BME defendants, who were more overrepresented in relation to three particular offences: prosecutions for robbery (39%), drug offences (39%), and possession of weapons (31%).

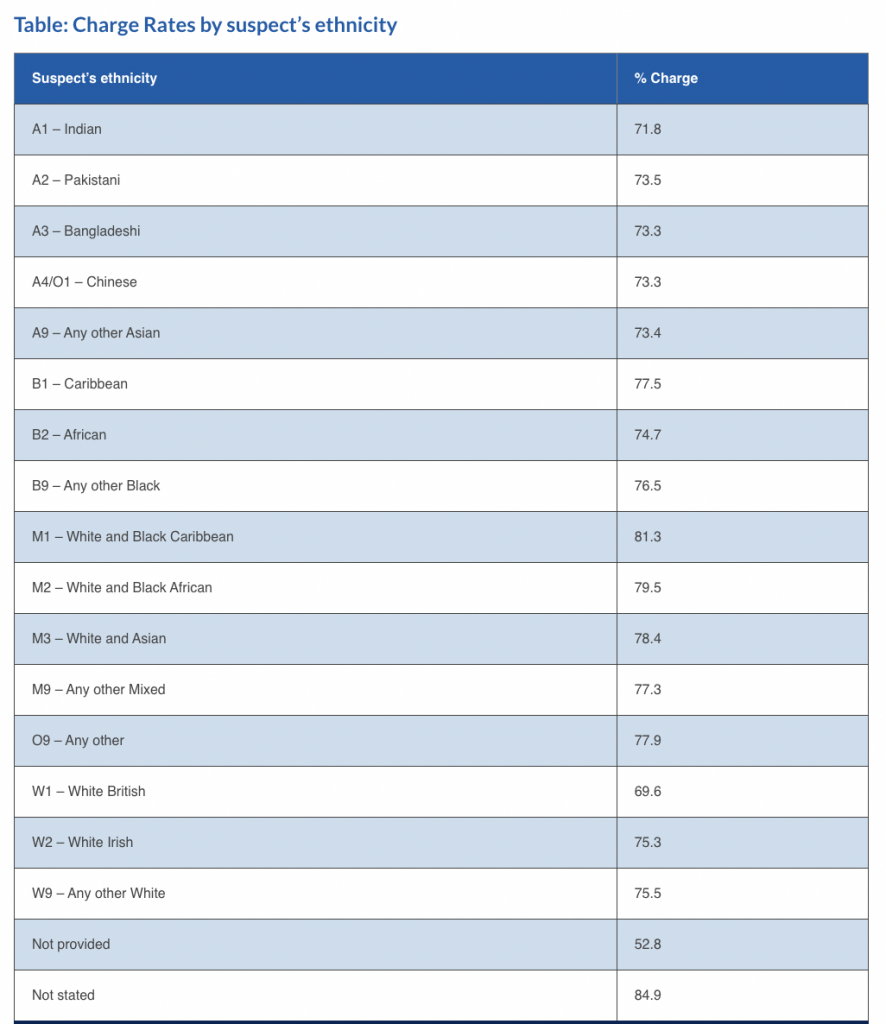

A University of Leeds study of CPS charging decisions, published in 2023, found that BME suspects are subject to disproportionate prosecutions. White suspects are charged in 69.9% of cases, Asians between 71.8% and 73%, black Caribbean suspects 77.5%, mixed white/ black African suspects 79.5% and mixed white/ black Caribbean suspects in 81.3% of cases – a rate nearly 12% higher than white counterparts for similar offences.

In addition, many homicide joint enterprise prosecutions brought against black and minority ethnic youth are brought using information about people’s associations, friends, families, use of social media, and even music preferences. The identification and stigmatisation of groups as a ‘gang’ in the prosecution process widens the net, enabling multiple prosecutions. However, the government does not provide data on ethnicity in such prosecutions. After JENGbA supported by Liberty challenged the Crown Prosecution Service and the Ministry of Justice for breach of the Equality Act 2010, the CPS agreed a pilot scheme to monitor data on the age, race, sex and disability of those prosecuted under joint enterprise, as well as to monitor when joint enterprise prosecutions have been presented as ‘gang-related’ cases, and whether the CPS’s own guidance on gang-related cases has been followed. The data, which was drawn from 6 of the CPS’s 14 regions, was released in September 2023. It revealed that more than half of those prosecuted under joint enterprise are from minority ethnic backgrounds (56% of defendants) with black people (30% of defendants) 16 times more likely be prosecuted. Children and young people made up over half (54%) of the defendants in these CPS pilot cases, and these young people were disproportionately likely to be from Black Asian and other minority ethnic backgrounds.

Once a decision has been taken to prosecute in serious crimes such as alleged gang-related cases, there is no meaningful regulation, or even monitoring of how the criminal justice system uses rap as criminal evidence. A University of Manchester study Compound Injustice found that rap and drill music was used to prosecute cases in England and Wales involving 252 defendants over three years ( a total of 68 cases), with the music genres used as indirect or ‘bad character’ evidence to suggest violent mindset, intention to commit serious harm or gang membership. 84% of defendants were minority ethnic people, with 66% of those Black, compared with 4% of the overall English and Welsh population, with a further 12% Black or mixed. A study published in the IRR’s journal Race & Class finds that bloated group prosecutions are the norm in music-facilitated cases with violent rap lyrics used to build secondary liability in group prosecutions by exploiting drill’s power to invoke stereotypes and mislead the courts. Compound Injustice found that 53% of the cases of rap and drill related prosecutions were joint enterprise prosecutions.

SENTENCING

Black, Asian and minority ethnic people were more likely than white people to be sentenced to immediate custody for offences which can be tried in the Crown Court (indictable offences). In 2018, according to government statistics, 37% of Asian and Chinese people convicted for indictable offences were sentenced to immediate custody, compared to 35% of black people, 34% of those from a mixed ethnic background and 33% of white people.

Of those sentenced at court for weapon possession offences in 2018, black defendants had the highest custody rate (ie, the percentage of offenders given an immediate custodial sentence, out of all offenders being sentenced in court for indictable offences) at 42%, whereas the custody rate for all other ethnic groups varied between 31% and 37%.

A 2016 study of joint enterprise convictions found that of young male prisoners serving 15 years or more, 38.5% were white, 57.4% BME and 38% black. Joint enterprise prisoners who identify as BME were significantly younger than their white counterparts and were serving longer sentences on average.

A second study, published in 2022, found approximately 30% of all joint enterprise defendants convicted for homicide were from black and minority ethnic communities, rising to 40% of those convicted in cases involving two or more defendants, and 50% of those convicted in cases involving four or more defendants.

Overall, the average custodial sentence length (ACSL) has been rising in general in recent years, but the rise has been steeper for BME offenders. For example, between 2009 and 2019 the ACSL rose by 4.9 months for white offenders and by 8.0 months for BME offenders, almost double the amount of time. In 2020 the ACSL for white offenders was 19.6 months, for black offenders 26.8 months, 28.6 months for Asian offenders and 24.4 months for mixed-heritage, Chinese and ‘other’ offenders.

The most recent (January 2023) race equality police briefing, which draws on defendant appearances in magistrates’ and crown courts in England and Wales, has found significant ethnic disparities in remand and sentencing. Ethnic minorities were more likely than their white counterparts to be sent to crown court for trial, to be remanded in custody when they appear and receive custodial and longer prison sentences. Defendants self-reporting as Chinese were found to be 60% more likely to be held on remand than those who identified as white British. The percentage was 37% for ‘other white’, between 22% and 26% for ‘mixed’ and between 15% and 18% for the black group. A custodial sentence was 41% more likely for Chinese defendants, 22% for the ‘other white’ and black African groups, between 16% and 21% for Asian groups and between 9% and 19% for the black categories.

In addition asn analysis of Ministry of Justice data obtained by the Guardian and Liberty Investigates reveals that in 2022 black defendants were imprisoned on average for 70% longer than white counterparts on remand, although they were more likely to be acquitted, and defendants of all minority ethnic backgrounds spent considerably longer on remand.

PRISON

Despite making up 18% of the population of England and Wales (2021 census), BME prisoners are significantly overrepresented in the prison system, with approximately 28% of the overall prison population from a BME background in 2022.

In 2020, the adult prison population comprised 73% white, 13% black, 8% Asian, 5% of mixed ethnicity and 1% from other ethnic groups. However black people, according to the 2021 census, make up just 4% of the general population, meaning they are over three times as likely to end up in the prison population.

Disproportionality does not end here but spills over into the use of force in prison as well as probation service risk assessments and conditions for prison release. Ministry of Justice statistics reveal that black prisoners are seven times more likely to have pepper spray used against them than white prisoners: PAVA synthetic pepper spray was used on a total of 732 prisoners between April 2019 and November 2022, of whom 316 were black, 255 white, 85 mixed race, 76 Asian or ‘other’.The UK National Preventative Mechanism’s annual report (2022/23) also expresses concern about the greater use of force against Black prisoners as well as restrictive measures against Black people in mental health settings.

The London Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) acknowledges that nearly a quarter (22%) of knife crime offenders tagged on release from London prisons in 2021 were black British Caribbean, and 16% were black African. More than half (57%) were aged 18-24 and nearly all (98%) were male.

Young people in custody

David Lammy MP highlighted in his 2017 report into the criminal justice system his concern with youth justice. Youth Offender Institutions (YOIs) were established by the 1998 Crime and Disorder Act, with a view to reducing youth offending and reoffending and, he found, had been largely successful in fulfilling that remit. Yet despite this fall in the overall numbers, the BME proportion on each of those measures had risen significantly. Over the ten years from March 2006 to March 2016:

The BME proportion of young people convicted for a first offence rose from 11% to 19%;

The BME proportion of young people convicted for a subsequent offence rose from 11% to 19%;

The BME proportion of youth prisoners rose from 25% to 41%.

In 2019, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons found that 51% of boys and young adult men in young offender institutions (YOIs) in England and Wales were from a BME background; at Feltham YOI in west London, 71% of inmates were identified as BME. In 2021-2, the proportion of children in YOIs and Secure Training Centres (STCs) who were BME had risen to 56%, the highest proportion on record.

Foreign national prisoners

Foreign nationals are overrepresented in the criminal justice system. There were just under 10,000 foreign national prisoners in English and Welsh prisons in December 2022, making up 12% of the prison population. The most common nationalities after British nationals in prisons are Albanian (13% of the FNO prison population), Polish (8%), Romanian (8%), Irish (6%), Lithuanian (4%), and Jamaican (4%).

[1] From May 2022, changes were made to the conditions under which a section 60 search could be carried out. These included:

Reducing the rank of authorising officer from senior officer to inspector; relaxing the grounds from a reasonable belief that serious violence will take place to a belief that it may take place; increasing the length of time the Section 60 order can be in place from 15 to 24 hours; reducing the rank of officer who can extend the authorisation from senior officer to superintendent; increasing the maximum period of an extension to 48 hours; removing the requirement for forces to communicate to local communities in advance, where practicable, where a Section 60 order is in place.

[2] The only force to release data on the ethnicity and religion of those stopped under Schedule 7 is Police Scotland. The National Police Chiefs’ Council, which coordinates UK police forces, says the release of data for other forces could jeopardise security and that it does not have a central record of data about religion.