The question of loyalty to British traditions was already under attack thirty years ago in relation to the work of the Institute of Race Relations.

As Britain reels from the fallout from the the Paris killings, the question of British values – who belongs to the nation and how that should be expressed – have been placed centre-stage.[1] Those who now greet the Roger Scrutons, Norman Tebbits, Leo McKinstrys and Richard Littlejohns as the leaders of a culture war over British identity should be aware that this is history repeating itself – both times as farce.

From 1982-1986, when the Institute of Race Relations produced three booklets[2] for young people filling the lacuna about the derivation of racism (and immigration to the UK) in slavery, colonialism and imperial endeavours, attempts were made not just to ban those books from schools and shops but to close down the IRR run by the ‘racially mischievous Sri Lankan Marxist’ A. Sivanandan[3] (who had coined the phrase ‘we are here because you were there’). This was not a culture war, it felt, to those of us who lived through the vilification in the press, parliament, on our doorstep, and then by funders who took fright, like a real war for our very existence.

Anti-racist not multicultural education

From the mid-1970s, multiculturalism was beginning to find purchase in education, supposedly to help teachers address the cultural diversity of the classroom. It concentrated on teaching children about religions, feasts, festivals, customs, food, dress etc other than the British. We at the IRR, amongst other groups at the time, realised that it actually did little to address the increasing racism in society, which included a growing and vociferous extreme-right party, the National Front. We were not, we thought, doing anything that radical and we spelt out our perspectives on ‘anti-racist education’ (in the most respectable of places) in evidence to the Secretary of State’s Committee of Inquiry into the Education of children from Ethnic Minority Groups, established in 1979 as the Rampton Committee (and which became the Swann Committee and Report):

From the mid-1970s, multiculturalism was beginning to find purchase in education, supposedly to help teachers address the cultural diversity of the classroom. It concentrated on teaching children about religions, feasts, festivals, customs, food, dress etc other than the British. We at the IRR, amongst other groups at the time, realised that it actually did little to address the increasing racism in society, which included a growing and vociferous extreme-right party, the National Front. We were not, we thought, doing anything that radical and we spelt out our perspectives on ‘anti-racist education’ (in the most respectable of places) in evidence to the Secretary of State’s Committee of Inquiry into the Education of children from Ethnic Minority Groups, established in 1979 as the Rampton Committee (and which became the Swann Committee and Report):

Your terms of reference are concerned with ‘the educational needs and attainment of children from all ethnic minority groups’, particularly West Indian children. We feel, however, that an ethnic or cultural approach to the educational needs and attainments of racial minorities evades the fundamental reasons for their disabilities – which are the racialist attitudes and the racist practices in the larger society and the educational system itself.

Ethnic minorities, we submit, do not suffer disabilities because of ethnic differences as such … but because such differences are given differential weightage in a system of racial hierarchy.

That is not to say that the difference in language, customs, values etc., of different ethnic groups cannot be mediated by the educational system and even help to change attitudes, but to say that such mediation is content to tinker with educational techniques and methods and leave unaltered the racist fabric of the educational system. And education itself comes to be seen in terms of an adjustment process within a racialist society and not as a force for changing the values that make that society racialist.

Our concern therefore is not centrally with multicultural multiethnic education, but with anti-racist education (which by its very nature would include the study of other cultures). Just to learn about other people’s cultures, though, is not to learn about the racism of one’s own. To learn about the racism of one’s own culture, on the other hand, is to approach other cultures objectively. (emphasis added)[4]

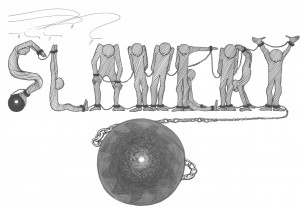

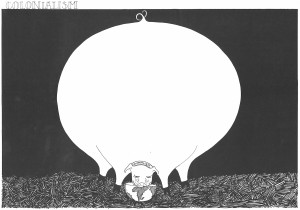

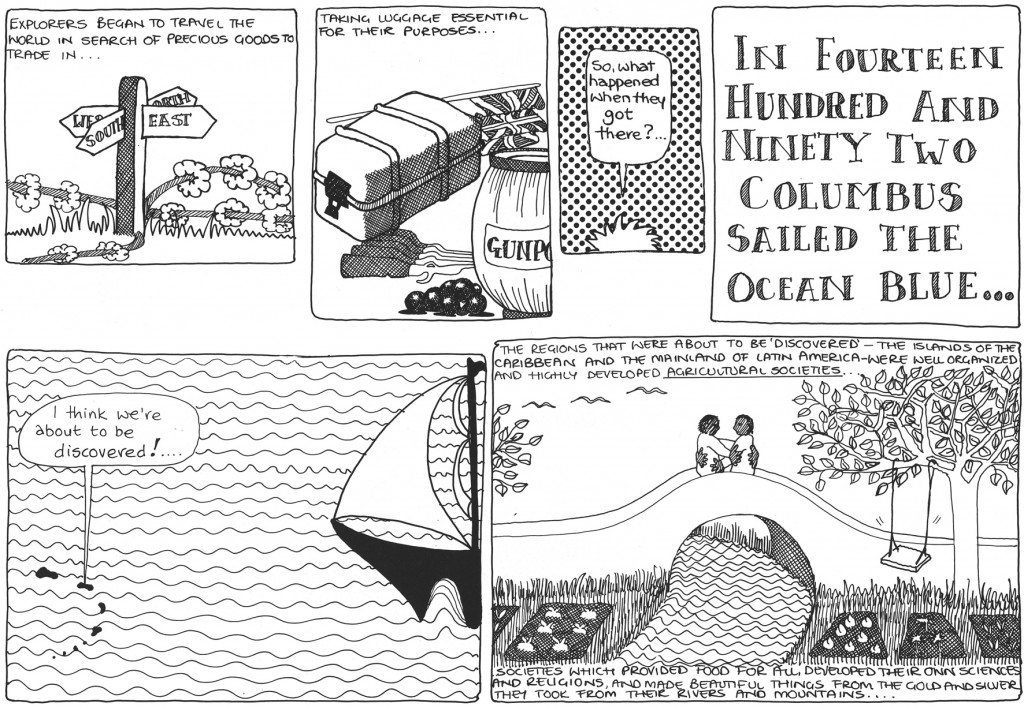

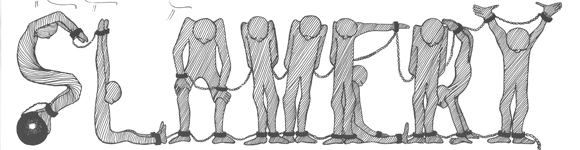

We set about teaching about racism in three illustrated booklets. The first, entitled Roots of racism (published in May 1982) covered the drive for conquest, dominance of Spanish and Portuguese colonialism, the colonial system and how that fed into Europe’s development – in particular through the Industrial Revolution – slavery and the genesis of racism. The second, Patterns of racism (published in July 1982) dealt with the different ways racism and colonialism developed in North America, Australia and New Zealand, Latin America, the West Indies and India and concluded by looking at the racialist culture fostered by imperialism.[5] The third, How racism came to Britain (published in 1985), aimed at younger children, used a cartoon format to examine the origins of British racism in slavery and colonialism and show how racism came to dominate every aspect of black life in Britain – from employment and housing to immigration law and the political system.

We set about teaching about racism in three illustrated booklets. The first, entitled Roots of racism (published in May 1982) covered the drive for conquest, dominance of Spanish and Portuguese colonialism, the colonial system and how that fed into Europe’s development – in particular through the Industrial Revolution – slavery and the genesis of racism. The second, Patterns of racism (published in July 1982) dealt with the different ways racism and colonialism developed in North America, Australia and New Zealand, Latin America, the West Indies and India and concluded by looking at the racialist culture fostered by imperialism.[5] The third, How racism came to Britain (published in 1985), aimed at younger children, used a cartoon format to examine the origins of British racism in slavery and colonialism and show how racism came to dominate every aspect of black life in Britain – from employment and housing to immigration law and the political system.

If, as often happened with our publications, they had attracted little attention, then the whole endeavour would have died a death. But the opposite happened. Roots and Patterns appeared indeed to meet a need and there was then a whole host of anti-racist and socialist groups of teachers eager to use them. They were glowingly reviewed in over twenty papers and magazines, and especially those aimed at educationalists and teachers during 1982/3: ‘these books fill a gap in curriculum materials … in a professional and attractive way’, (Times Educational Supplement,23.7.1982); ‘well illustrated and closely argued books’, (ALTARF, 3.7.1982); ‘managed to expose the lies and half-truths about the rise of Britain … as an imperial power’, (Dragons Teeth, Autumn/Winter 1982); ‘essential reading for all teachers’ (Teaching London Kids, No. 19); ‘show clearly how the past weighs upon the present’ (Liberation, March/April 1983); ‘one of the best books on the origins and meaning of racism’ (Caribbean Times, 11-17 June 1982); ‘the history of black-white relations from the vantage point of the black experience’ (Advisory Centre for Education, No. 183 Nov/Dec 1982), ‘at every stage [they] point not only to the oppression but to the resistance movements’ (Tribune, 27.8.1982); ‘two powerful source books’ (New Society, 9.9.1982); ‘highly recommendable as material for the school curriculum and for those working with young people in informal situations’ (Youth & Policy, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1984).

The Right responds

They were bought in bulk by local education authorities and were reprinted six times. And then started the Right’s fight back – to reach, by 1985/6, after the publication of the cartoon book, something tantamount to a moral panic about anti-racism and the politicisation of education.

But in the first phase, the fight back was not so much about anti-racism per se as about the way Roots and Patterns taught a history which disrespected those great traditions of freedom and emancipation that Britain had brought to the colonies. They were all so one-sided. Where, for example, was William Wilberforce in the IRR’s account? Where the massive infrastructural developments Britain had brought to her colonies? That was the rumble that was begun by a teacher in an association for the teaching of history and was summed up in a leader in the Spectator in July 1985 which asserted that Roots presented ‘a particularly chilling example of a “history” textbook for schools’ which revealed a ‘hatred of “capitalist” civilisation’. ‘Europeans generally, and the British particularly are presented … as plundering barbarians … The British … never do anything but from the vilest of commercial motives – even the slave trade was abolished only because wage labour was more profitable’.

It was How racism came to Britain, a cartoon book of a mere 40-odd pages, that really put the political cat amongst the Thatcherite pigeons and led to a lengthy and consistent barrage against the IRR in the media and Parliament, a programme on Channel 4 and a book of denunciation. To understand the booklet’s impact, means understanding the politics of the time: a government under Margaret Thatcher, particularly after the Falklands War, determined to put its stamp both on neoliberal economics and the New Right libertarian philosophy and cultural conservatism necessary to underpin it. Left-of-Labour-controlled local authorities were simultaneously stretching their democratic and political brief and reach so as to resonate their policies with community concerns – particularly over social issues such as racism, sexism, homophobia, policing, minority rights and the planet. The think-tanks around the Thatcher government and their many hench-people in the media were only too primed to the ideological nature of the fight: the New Right against a potentially populist Left. In that sense the battle against the IRR was just a part – if a large one – of the fight also against the Greater London Council (GLC), especially its video about policing, the book for young people Jenny lives with Eric and Martin, and a host of innovations by left councils.[6]

It was How racism came to Britain, a cartoon book of a mere 40-odd pages, that really put the political cat amongst the Thatcherite pigeons and led to a lengthy and consistent barrage against the IRR in the media and Parliament, a programme on Channel 4 and a book of denunciation. To understand the booklet’s impact, means understanding the politics of the time: a government under Margaret Thatcher, particularly after the Falklands War, determined to put its stamp both on neoliberal economics and the New Right libertarian philosophy and cultural conservatism necessary to underpin it. Left-of-Labour-controlled local authorities were simultaneously stretching their democratic and political brief and reach so as to resonate their policies with community concerns – particularly over social issues such as racism, sexism, homophobia, policing, minority rights and the planet. The think-tanks around the Thatcher government and their many hench-people in the media were only too primed to the ideological nature of the fight: the New Right against a potentially populist Left. In that sense the battle against the IRR was just a part – if a large one – of the fight also against the Greater London Council (GLC), especially its video about policing, the book for young people Jenny lives with Eric and Martin, and a host of innovations by left councils.[6]

Anti-racism was a particular bugbear for all factions of the New Right – encompassing as it did issues relating to national culture, cultural relativism, and so-called values as well as their hatred of social engineering and state intervention. (For the New Right, as for Thatcher, there was no such thing as society, only the individual, and this belief seeped into its understanding of racism and explains the later campaign, post-Macpherson, against the concept of institutional racism.[7]) Both the Inner London Education Authority for its Guidance books on Race, Sex and Class (in 1983) and the GLC for its Anti-racist Year (1984) came in for attack. So did the 1985 Swann Report, Education for All (actually quite a tame document). And the New Right rallied around its own ‘race martyrs’, in Bradford headteacher Ray Honeyford and Jonathan Savery, a West Country teacher, who were, allegedly, the victims of political correctness turned witch-hunt. Anti-racism was being established as a new form of totalitarianism.

Racism, indoctrination and moral panic

It was into this febrile climate that How racism came to Britain was born in June 1985. Once again an IRR pamphlet got rave reviews for being ‘incisive yet fun’ in at least twenty-seven newsletters and magazines from Spare Rib to the Journal of Evangelical Christians, the Guardian, Multi-ethnic Education Review and Local Government Chronicle. The booklet, the first on racism in cartoon format, was aimed at children of 10-plus years, was educational but light-hearted, committed but witty. It told in broad brush strokes and some parody how history – early plunder and then slavery and colonialism – had helped create and reinforce the concepts behind racism and how racism had become woven into Britain’s social fabric while at the same time resisted by black communities under attack.

The linked spectre of political indoctrination on the rates and anti-racism was now entrenching itself. On 23 July, Edward Leigh MP, introduced a Ten Minute Rule Bill ‘to prevent political corruption in local government’[8] in which his speech, as reported in the Daily Telegraph, revealed the Institute of Race Relations (which, according to him, received £50,000 a year from the GLC!) was linked to all kinds of other shady leftwing organisations, including the Transnational Institute whose one-time director was the Chilean ambassador to the US, Orlando Letelier (later assassinated by Pinochet emissaries), whom, he alleged, had been an agent of Cuban Intelligence, and had other Marxists on its board. (The linking of the GLC and the IRR was not gratuitous, the Right was gunning for its police committee which funded radical projects and its acting head, Tony Bunyan, who had earlier sat on IRR’s board.[9])

But the first to sound the alarm in the media was ultra-conservative Times columnist Ronald Butt in ‘The new breed of racist’ (25/7/1985) his attack on ‘a book of great wickedness, perverting history in a way that can only encourage among “blacks” a deep hatred of “white” society’. ‘No merit’ he writes ‘is given to the Europeans for abolishing … this ghastly trade in human lives … no flaw in pre-British India is indicated. There is not a word about the caste system, suttee and the intense subordination of women. Nor is there any merit in law-giving, administration and medicine. Nor in Africa is any single good thing to be said of the European colonial period.’ After paraphrasing the sections on racism in Britain, he ended by asking the Commission for Racial Equality, the Home Office and Parliament to close down on this provocation ‘to divide citizen from citizen; its logic can only be the fabrication of social unrest’.

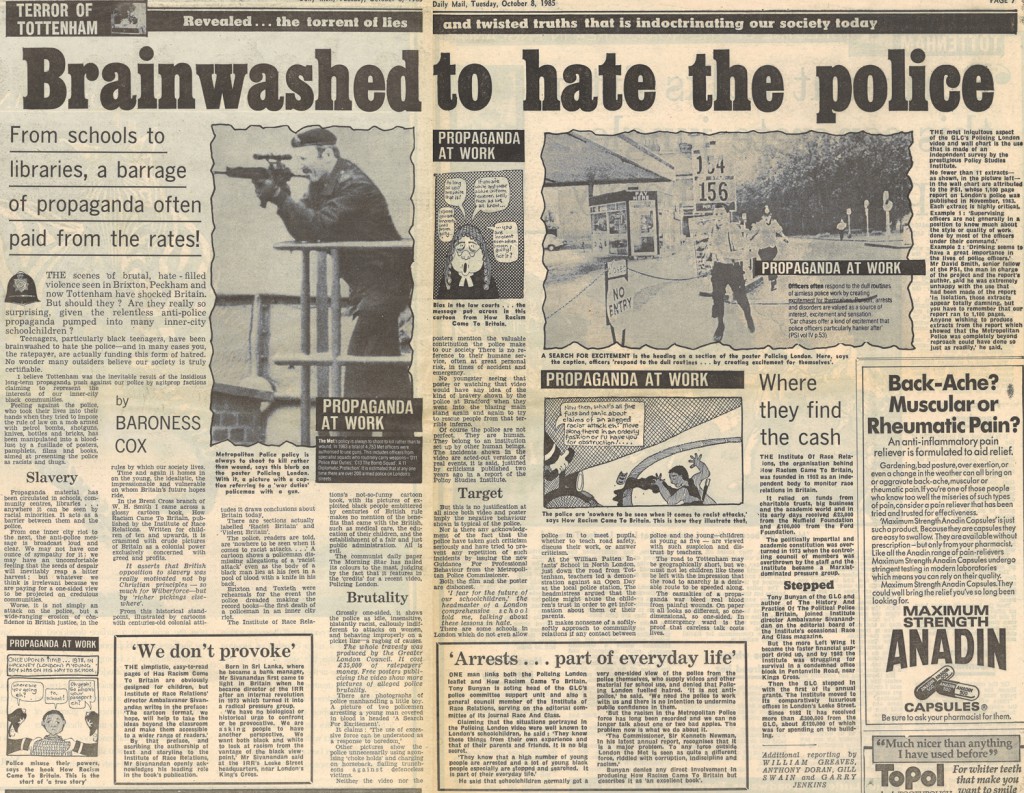

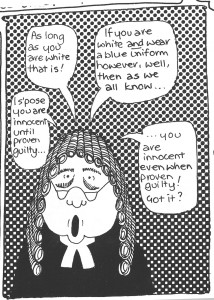

And the riots on 6 October on Broadwater Farm, in north London, in which PC Blakelock was killed, provided all the proof for rightwing educationalists Caroline, now Baroness, Cox, who had apparently been shocked to find the offensive cartoon book on sale in the flagship chain store WH Smith in London’s first US-style shopping mall. In a double-page spread entitled, ‘Brainwashed to hate the police’ she let rip in the Daily Mail on 8 October about why one should not be surprised at the hate-filled violence seen in Brixton, Peckham and now Tottenham because of the ‘relentless anti-police propaganda pumped into many inner-city school children’. She attacked the book for being ‘crude’ with no mention of the benefits that came with the British under colonialism and three cartoons illustrating the police and judiciary were reproduced to reveal ‘the torrent of lies and twisted truths that is indoctrinating our society today’. Cox’s view now held sway about the book’s depravity and the Telegraph was happy to host her opinions. ‘It is grotesquely dishonest and blatantly intended to stir up racial conflict’ she told the paper.[10] ‘It is an extraordinary example of Marxist exploitation of the crisis of capitalism by encouraging manifest hatred of the police’, she went on. The next day the paper got the IRR’s former chairman, Michael Caine of multinational Booker McConnell, ousted by members in 1972, to denounce the IRR as dominated by Marxists. This was followed by an expose of the book’s contents, along with the reproduction of a cartoon about judicial bias, in the Sunday Telegraph.[11] And then Ronald Butt added his pennyworth with, ‘Race: weapon in a new class war’[12] in which, apart from laying into Haringey Council’s black leader Bernie Grant, he asserted a conspiracy whereby leftists (including the Marxist-dominated IRR) manipulated young blacks (‘for there was organisation in their riots’) and taught them anti-police attitudes. This was followed by Tom Hastie in ‘The English become the lost tribe of race relations’[13] which laid in to the government race body the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) – which he had heard called the Campaign of Revenge on the English – and once again the cartoon book was condemned, this time for distorting the Atlantic slave trade as ‘inflicted upon helpless, innocent Africans solely by wicked whites, instead of being the Afro-European commercial enterprise it most certainly was.’

Moving up a political gear

But Cox and Co. – fellow travellers on the New Right, especially those grouped around Salisbury Review – now appeared to change tactics from taking simple vitriolic pot shots in the press, to become more serious and practical in their culture war. (In the process, the connection with the GLC,[14] waste of tax payers’ money and even the incitement of the young, gave way to their main thrust against the distortion of Britishness.) Dr John Marks, at a fringe meeting at the Conservative Party conference organised by the Freedom Association, put forward an 8-point plan to tackle the ‘political subversion of education’, his evidence including How racism came to Britain.[15] And in the following year they carried the fight into government. The work of the IRR and especially the cartoon book were examples quoted at length in a number of parliamentary debates in February, on the Local Government Bill (4 February 1986) [16] and on ‘Education: Avoidance of Politicisation’ (5 February 1986).[17] And when Education Secretary Sir Keith Joseph was about to quit in May 1986, in his parting speech, on educational policy that was right for the country’s ethnically mixed society, he singled out How racism came to Britain as the example of dangerous bad practice.[18] But it was in fact his successor Kenneth Baker who decided in September 1987 to alert the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) and the Department of Education and Science to his exhortation that the ‘categorical, aggressive and simplistic’ book should not be available in schools, especially primary schools – using the argument about ‘political indoctrination’ enshrined in sections 44 and 45 of the 1986 Education Act.[19]

To this viewpoint he had no doubt been urged by the phalanx of New Right soldiers (some of whom, like Caroline Cox and John Marks, had already been actively engaged in campaigning against the supposed politicisation of education, especially at North London Polytechnic[20]) including Antony Flew (Salisbury Review contributor, Freedom Association and Centre for Policy Studies), Ray Honeyford,[21] Tom Hastie (history teacher), Dennis O’Keeffe (editor of The Wayward Curriculum) and Roger Scruton (editor of the Salisbury Review and writer on education and indoctrination)– whose contributions were gathered together by Frank Palmer in the book Anti-racism: an assault on education and value,[22] where almost every chapter condemned the IRR and a whole section ‘Materials of Propaganda’ cited the cartoon book at length and one chapter by Salisbury Review contributor and social worker David Dale was on ‘Racial mischief: the case of Dr Sivanandan’. The cartoon book was ‘deplorable’, ‘simplistic caricature’, ‘[of] anonymous authorship’, stereotypes, ‘eurocentric in presentation of the slave trade’, ‘bash the Brits … [denied] capacity for human compassion’, ‘unleavened by thought’, ‘strikingly biased account of Britain’s record of colonialism’, ‘[intended to stir up] racial tension hatred and conflict’. And Sivanandan (‘a central reference point for antiracists’) is a ‘vulgar Marxist’ who writes of treachery and collaboration and lauds black ‘superbeings entrusted with the collective truth which only revolution can realise’, ‘exploitation is the plot of history’, ‘lacking … any acknowledgement of individual autonomy’. The three educational pamphlets are critiqued – and again Britain’s role in abolition picked out. Finally, Sivanandan is presented as the enemy of black people for denying them the chance of individual advancement.

All New Right themes are there: anti-racism is political (leftwing even Marxist) indoctrination, what we want is interpersonal harmony, those who don’t support anti-racism are hounded, anti-racism is totalitarian, terms such as racism have been hijacked and redefined by anti-racists, anti-racists demand an unachievable equality of outcome, our culture and morality are being debased by anti-racism’s ‘witchcraft’ of false claims and demands. (Here were the straw men of Political Correctness in all their glory before the term was even conceived!)

It is worth, given his enduring influence in today’s culture war, quoting from Scruton’s fairly sedate (as opposed to ranting) contribution, which effectively established the New Right position on cultural relativism – i.e. multicultural education from his own (class) perspective:[23]

[the seven types of activity constituting culture] serve to bind people together in a common enterprise … they are ways of ‘belonging’ to the larger world of human society, and of affirming one’s reality as a social being … not all ways of belonging have the same structure. The rehearsal of our shared nature in ritual, ceremony and faith is more profoundly rooted than … resolution of conflict through law, and … obedience to civil society … [our culture] tries to accommodate conflict and forge common bonds between people by means of contract, law and a shared sense of justice … precisely what distinguishes the modern from the medieval state …

‘The child brought up in the British way of doing things is encouraged to question and to criticise, to seek fair play and impartial judgement’, and therefore, he goes on, ‘does not need that presentation of “alternatives” which so many educationalists wish to foist on him.’ British permeable openness (which is sustained by the traditions of Christianity) prepares children for a mixed society ‘far more effectively than does, for example, the culture of modern Pakistan’. And it is in ‘high culture’ that openness is ‘at its most developed’.

Scruton’s influence did not end in the book; he was central to a television programme made by the Diverse Reports team for Channel 4 in 1986. Imagine our distress – going out for sandwiches one lunch time and finding our building being avidly photographed by a full film crew. That was the first we knew about a programme being made on The Anti-racist Tendency (a title to echo the leftist Militant Tendency which had infiltrated the Labour Party) and IRR’s sinister part in it. This hatchet job, starring not just Roger Scruton, but also Ray Honeyford and Trevor Phillips (for the proposition, not the opposition), was a gross distortion of anti-racism. That anti-racism existed anyway as a body of thought was hotly contested by Sivanandan, who, reluctantly took part in the programme, transmitted in July 1986, making a slight mockery of the whole exercise. Though a number of people and campaigns complained to Channel 4 about the programme’s obvious bias; it was warmly welcomed in a section of the media.[24]

In case you are wondering, the New Right did not manage to put us out of business, nor did our books actually get banned from schools, and continue to sell to this day. Last week, we were interviewing prospective IRR volunteers, and a young post-grad student pulled something from her bag. ‘My mother’s a geography teacher and she wanted you to know how much this meant to her. Perhaps’, she added shyly, ‘something rubbed off on me, too’. It was a very battered copy of How racism came to Britain.

Related links

You can buy the educational books here

Huge thanks to Jenny Bourne for this very poignant account of the IRR’s role in countering British imperialist ideology in schooling and education and the British state’s refusal to set an agenda for schools that was about understanding and confronting the legacy of Empire, including the racialisation of immigration, deprivation, crime and much else besides. At this time when Western Europe despite its imperialist past (and present in many areas of the world) is Islamicising barbarism and foregrounding western values as if they invented and continue to curate them, this is an important reminder of our struggle to help British children understand a past which the state preferred them not to know and to build a future based on that understanding. Kenneth Baker refused to have Ian Macdonald’s report of his investigation into the racist murder of Ahmed Iqbal Ullah at Burnage High School in Manchester in September 1986, ‘Murder in the Playground’, placed in the House of Commons library. The Department of Education did its best to ensure that schools across the land did not learn the important lessons of Burnage, lessons framed in an analysis of the intersection of race and class in education and society. Jenny’s historical account of the IRR’s resistance to the state’s insistence on justifying imperialism and the racism it spawned, rather than on dealing with the legacy of empire should be compulsory reading for every trainee and classroom teacher and every civil servant.

These books have such staying power! I used them with middle and high school students in the United States in the 1990s, when racism was used interchangeably with prejudice (in curricula) or seen as something that victimized whites (in the courts). They really helped kids grasp what imperialism and racism were all about – and some of those young people are now involved in fighting racism in the criminal justice system and its various other institutional forms. Thanks for this excellent reminder of the context in which they were created, Jenny Bourne.