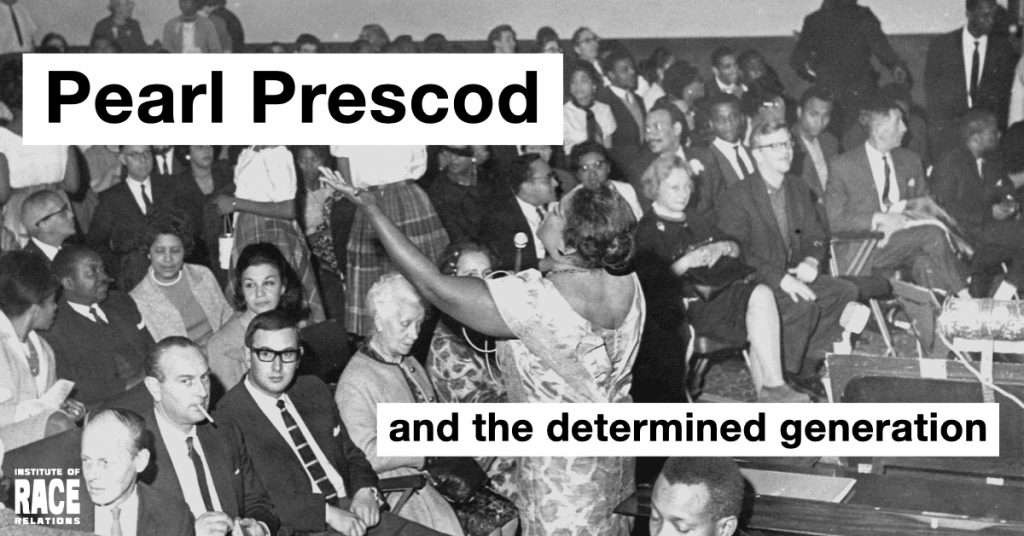

Earlier this year, the IRR produced a pamphlet on the life of actor, singer, activist Pearl Prescod. The first female black actor at the National Theatre, in the 1965 production of Arthur Miller’s classic The Crucible. As the National revives the play, opening this week, poet and educator Chris Searle reminisces about seeing Pearl as Tituba and explores the limited roles for Black actors at the time and those who, still relatively unknown, broke through.

In 1965 Pearl Prescod became the first black actor to be cast in a National Theatre production, as Tituba the Barbadian slave in Arthur Miller’s ‘The Crucible’, directed by Laurence Olivier, in which the brutal 1692 witch-hunting and trials in Salem, Massachusetts, became dramatically emblematic of the McCarthyite persecutions of progressive and left-leaning Americans.

When Pearl came onto the stage in the first scene of ‘The Crucible’, I remember well the dramatic energy and verve she radiated, and I remember too how disappointed and deflated I felt that her character had been written as so shallow, brief and undeveloped in the play, and how little her skill and exuberance were exploited.

It reminded me of a few years earlier in 1963, when I was still at school, I had come to the Old Vic production of ‘Othello’. It featured Errol John, the Trinidadian actor and writer of the classic Caribbean barrack-yard drama ‘Moon on a Rainbow Shawl’, who became the first black actor to play Othello on the Old Vic stage. I had seen Errol John in films like ‘Guns at Batasi’ with Richard Attenborough as a mutinous African soldier and ‘The Nun’s Story’ with Audrey Hepburn as a superstitious medical orderly, where he had, in the outright racist manner of the times, been given parts acting out African losers and characters born to serve or be defeated, under British or Belgian colonialism. Sitting in the high reaches of the Old Vic gallery watching his Othello, I looked down over a virtually empty theatre as John gave a powerful authenticity, authority and artistry to the character, while a white Australian, the remarkable comic actor Leo McKern, played a treacherously adroit Iago as if his character-acting had imbibed all the hostility of the White Australia Policy. The phalanx of theatre critics had criticised John for the way he spoke Othello’s lines. They were the same critics who two years later were to shower praise on Olivier’s Othello, a white caricature of blackness with his boot-blacked skin, rolling gait and round-eyed glares. John had played two parts in the Old Vic repertory of 1962-3: his Othello, where any attentive listener could catch the lilt and beauty of his Trinidadian creole vernacular, and the Prince of Morocco in ‘The Merchant of Venice’

(‘Mislike me not for my complexion,

The shadow’d livery of the burning sun

To whom I am a neighbour and near bred.’)

John had other major parts denied to him, largely due to his ‘complexion’, but not to a white Australian. Leo McKern was given Subtle in Jonson’s ‘The Alchemist’ and the title role in Ibsen’s ‘Peer Gynt’. Such parts were certainly not to be offered to a black Caribbean actor in those benighted theatrical times, and this is what Pearl’s powerful acting generation was up against. It was to be the next generation of Caribbean actors who eventually broke through – Norman Beaton, Mona Hammond, Rudolph Walker, many of the acting in television comedies or in plays written by the Trinidadian playwright Mustapha Matura like ‘Welcome Home Jacko’, ‘Play Mas’ or ‘Nice’ – plays not to be found so often on prestigious West End stages, but more often at the Theatre Royal, Stratford E.15 or at the Factory in Paddington.

Pearl Prescod died prematurely in 1966, at a time when her acting genius was on the cusp of at last being recognised by British mainstream cultural life. Twenty years later the writer of Guadeloupe, Maryse Condé, wrote her proud, rebellious and inspiring novel, ‘I, Tituba’, in which its protagonist returns to Barbados and identifies with a new generation of insurgent slaves, giving them succour and the energies of her spiritual power: ‘I could only feel tenderness and compassion for the disinherited and a sense of revolt against injustice’, she concludes. Miller’s ‘witch’ has become Condé’s revolutionary: ‘I am hardening men’s hearts to fight,’ she asserts. ‘I am nourishing them with dreams of liberty. Of victory. I have been behind every revolt. Every insurrection. Every act of disobedience.’

That is more like Pearl Prescod. If only Miller had been able to read ‘I, Tituba’ or Hilary Beckles’ riveting history of the enslaved black women in Barbados, first published in 1989, ‘Natural Rebels’, he may well have written an entirely different characterisation of Tituba, one truly fitting for such powerful black actors as Pearl Prescod to play. But 1965 was another world. In the National Theatre programme of ‘The Crucible’ there is a page-size advertisement extolling the pleasures of South African Airways’ flights to Johannesburg during Apartheid’s most frenzied years, with the enticing slogan for white audiences: ‘The South African Holiday, a promise of enchantment.’

One personal endpiece. In 1968 I went to teach in Tobago and found myself living very close to Lambeau where my friend, cultural activist, dancer and the school’s geography teacher, Cyril Collier, lived. In 1963 Pearl had helped organise in London, with the patronage of cricketer Learie Constantine, an ‘All-Star Variety Concert’ in St. Pancras Town Hall as a benefit for the victims of Hurricane Flora, which in 1963 caused terrible damage and loss of life in Tobago. My students and I wrote and performed a play which dramatised Flora’s rampage and the production won the Trinidad and Tobago National Schools Drama Competition.

54 years later, I’d like to dedicate the play, called ‘I Thought You Loved the Fishermen’ to Pearl and her generation of determined Caribbean cultural comrades: Forward Ever!