We unpick Sir Keir Starmer’s ‘fighting crime is a Labour cause’ speech of 23 March and link his failure to use the term ‘institutional racism’ with the Met Commissioner’s disavowal of the term to the London Assembly Police and Crime Committee the day before.

Given the long history in the UK of racialised cannabis moral panics and the establishment of black youth as urban ‘folk devils’, seasoned campaigners were dismayed when the Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer, during a speech at Port Vale FC, drew on a vignette of a family in his constituency whose life was blighted ‘as every night cannabis smoke creeps in from the street outside into their children’s bedroom’. The speech foregrounded the idea that a section of society (criminals ‘swanning around our communities’) was operating outside the rule of law and ‘getting away without punishment’. The Labour leader delivered his speech, which coalesced around the idea of ‘respect’ and ‘the rule of law’, two days after Louise Casey’s damning findings about institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia in the Metropolitan Police. Starmer referenced her report, blaming the Met for tarnishing the reputation of police forces everywhere, and claiming only Labour could ‘restore confidence in every police force to its highest ever level’. But, surprisingly, given Casey’s evidence, one of the most significant causes of mistrust in the police, whether in London or elsewhere, was for him located in its inability to ‘fight the virus of anti-social behaviour’ of criminals.

https://twitter.com/jrc1921/status/1638887502025981952?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

The big idea – Respect Orders and more Fixed Penalty Notices

So the big policy announcement of Starmer’s speech was not in relation to ‘bad policing’ but his promise to extend anti-social behaviour orders, to include a new ‘Respect Order’, backed by getting ‘clever’ (his word) with Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs). The Labour leader, who makes much of his background in civil liberties and human rights, appears to have forgotten that FPNs were disproportionately used against BME communities during the Covid pandemic, with people of colour 54 per cent more likely to be fined than white people and BME people in England and Wales almost seven times more likely to be fined than white people.

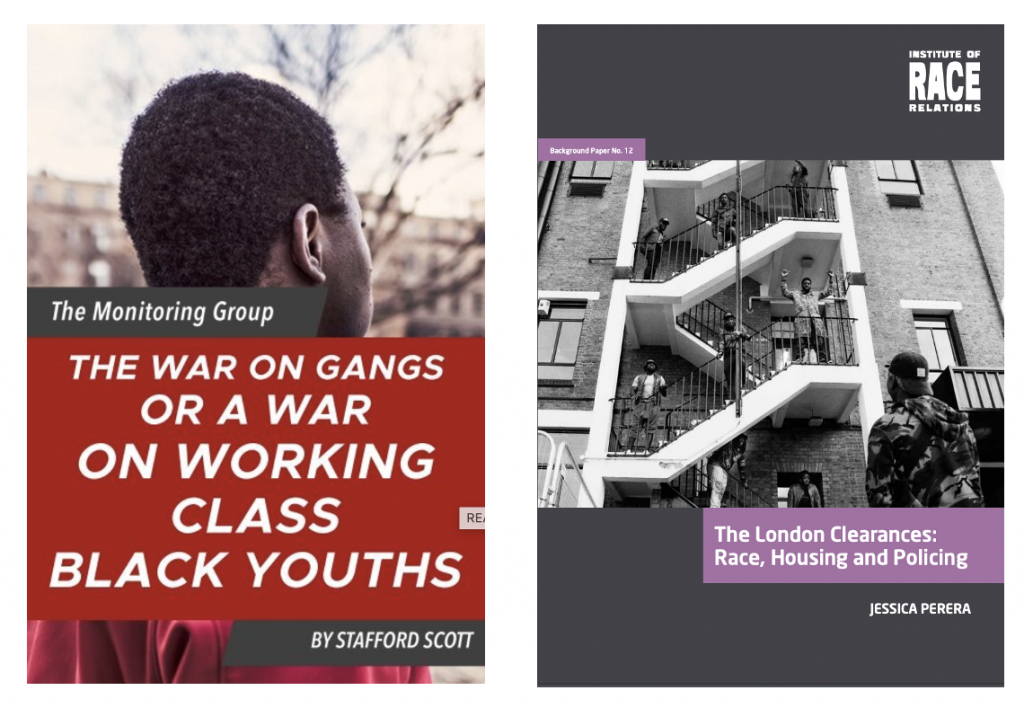

The Labour leader’s ‘clean streets are safe streets’ pledge suggests that the next Labour Party manifesto will be based on a re-run of the Blair years’ ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’ pledges. New Labour was responsible for the creation of over 3,000 new criminal offences, and for the regime of anti-social behaviour orders, a plethora of new police powers and a massive expansion in multi-agency policing which further criminalised young black people. Veteran campaigner Stafford Scott sees all this as part of a war on working class black youth. And as Jessica Perera and I have previously argued, all that this expanded criminal justice system bequeathed to us by the Blair years achieved was to blur the line between criminal, civil and administrative law powers, leading to the further criminalisation and ‘marginalisation of young black people and their class-based cultural rights’.

Opposing the decriminalisation of drugs while ignoring BME concerns

And it’s here that we find the real significance of Starmer’s foregrounding of cannabis use as one of the chief archetypal anti-social behaviour issue of our times. It is well known that Starmer opposes the decriminalisation of those carrying small amounts of cannabis, ketamine or speed, and has set himself against London mayor Sadiq Khan’s plans to bring down the arrest rate of under 25s in this respect. But whatever Starmer’s personal views on the decriminalisation of drugs, one would have thought that in a speech that boasted his passionate hatred of inequality and injustice, he might have addressed the evidence that shows that cannabis laws are criminalising the black community at disproportionate rates. He might even have had a glance at his close colleague David Lammy’s review (2016) which found that sentences for drugs offences were around 240 per cent higher for BME offenders. He could also have had a quick chat with Hackney MP Diane Abbott who would have reminded him of the case of a 15-year-old Child Q who was strip-searched when she was menstruating because her teacher thought she smelt of cannabis. Surely his advisers have told him that over half of the 799 children aged between 10 and 17 strip-searched between 2019 and 2021 while not in custody were black (436) and three-quarters were from ethnically diverse backgrounds (607). There was no outcome or arrest in just under half of the cases, and most were linked to searches for drugs.[1]

Why use the term ‘institutional discrimination’?

And it’s not just here that Starmer’s promise to ‘boost confidence in police’ misses the point. Was it an accident that not once in his speech did he mention the term ‘institutionalised racism’, though he referred to ‘institutional failings’ relating to ‘the racism, misogyny and homophobia we have seen in the Met’, and once referred to the problem of ‘institutionalised discrimination’ in the police? Implicit in a muddled term like institutional discrimination is the de-linking of discrimination (an abstract colour-blind term) from racism, and the erasure of racism from structures. In Starmer’s terms, the police discriminate because they have failed to modernise, not because their policies and procedures systematically target BME communities. Thus, Starmer now seems to reject Macpherson’s finding of institutional racism in the Metropolitan Police, despite signalling in his speech that he considers Doreen Lawrence a close friend.

Two knights of the realm – the one the head of the Metropolitan Police, and the other the leader of the opposition – have two strikingly similar takes on institutional racism in the criminal justice system. But whereas Sir Mark Rowley’s denial of the term ‘institutional racism’ (an ‘ambiguous’ and ‘political’ term that could imply all police officers are racist) at least has the merit of being delivered in plain English, Starmer’s evasion, because it is couched in the colour blind language of ‘post-racial’ Britain, is more difficult to pin down. But ultimately, it is the same approach.