We reproduce here an article by Eddie-Bruce Jones, from his personal blog, reflecting on the counting of deaths.

In April, the Institute of Race Relations, as part of a day-long anniversary event, held a panel discussion called ‘Why do we count deaths?’ The question was posed as a provocation to help us address the questions: what does it mean to count. What are we doing when we count the dead?

We do not need especially good reasons to count loved ones when they die. Nor do we need reasons to count the deaths of strangers, for that matter. But there are reasons, and they are important to reflect on.

Before going further, it is important to note that counting the dead is tiring work. Counting as a means of illustrating the patterns of violence we witness certainly shapes our relationship with numbers. It dresses the dull mechanics of statistics in sounds and smells that make us dream of ghosts.  Nine has special meaning, at least for a while, because of Charleston. When I think of the nine killed in the Charleston Church, I think of the four young girls killed in the Birmingham church bombing of 1963. I think of the five clacks of a pistol as its magazine is fastened shut by a blossoming white supremacist and the six Black churches that burned in the south in the week after the Charleston shooting. I think of the seven winds blowing all around the cabin door in Nina Simone’s haunting redition of ‘The Ballad of Hollis Brown‘. Delivered by Nina Simone, the song is tempered with the knowledge of violence, mourning and ancestral memory. I think of the eight bullets fired at unarmed Walter Scott by a Charleston police officer in April, killing him. These hauntings take energy, and that energy has to come from somewhere. It’s like having too many files on your desktop, slows the whole computer down. It effects everyday life, for all of us. The draining of energy is serious business.

Nine has special meaning, at least for a while, because of Charleston. When I think of the nine killed in the Charleston Church, I think of the four young girls killed in the Birmingham church bombing of 1963. I think of the five clacks of a pistol as its magazine is fastened shut by a blossoming white supremacist and the six Black churches that burned in the south in the week after the Charleston shooting. I think of the seven winds blowing all around the cabin door in Nina Simone’s haunting redition of ‘The Ballad of Hollis Brown‘. Delivered by Nina Simone, the song is tempered with the knowledge of violence, mourning and ancestral memory. I think of the eight bullets fired at unarmed Walter Scott by a Charleston police officer in April, killing him. These hauntings take energy, and that energy has to come from somewhere. It’s like having too many files on your desktop, slows the whole computer down. It effects everyday life, for all of us. The draining of energy is serious business.

So why do we count the dead?

First, we count for institutional memory. Recording deaths helps us to commit their circumstances to the history books and to internal movement strategies. It also helps us to convince ourselves that we are not imagining things. We live with the ghosts that help us see reality more clearly, to know where it is we are living.

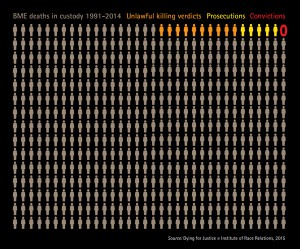

Second, we count to measure where we are as a society, to take the temperature. We’re counting not only those who have passed away, but we’re measuring death among the living – our spiritual and psychic death as a society. The Guardian has, for example, has set up a counter and a database on the deaths caused by police in the United States since January 2015 (@thecounted). The Institute of Race Relations has done an analysis of deaths in custody that features statistical analysis. These forms of counting do work to describe the state of our world.

Second, we count to measure where we are as a society, to take the temperature. We’re counting not only those who have passed away, but we’re measuring death among the living – our spiritual and psychic death as a society. The Guardian has, for example, has set up a counter and a database on the deaths caused by police in the United States since January 2015 (@thecounted). The Institute of Race Relations has done an analysis of deaths in custody that features statistical analysis. These forms of counting do work to describe the state of our world.

Sometimes, though, we make the mistake of thinking that the degree of our crisis is reflected only through the size of the death toll. For instance, the 900 who drowned in a single weekend off the coast of Italy received immense media coverage, in comparison to the continuous violence at the borders of Europe. That weekend marked a tragedy, but of course, the magnitude of violence cannot be measured by the death toll alone. Ta-Nehisi Coates, reflecting on the death of 22-year-old Kalief Browder after his years at Rikers Island jail in New York, offers that ‘numbers alone can’t convey what the justice system does to the individual black body’. He says this because the statistics that prove patterns of racism in the criminal justice system cannot do justice to the quality of physical, psychological and spiritual violence visited systematically upon Kalief and others like him. My work in Germany over many years on a single death-in-custody case also does not rely on numbers of death, but quality and pervasiveness of violence. Other thinkers, like Juan Amaya-Castro and Hillary Charlesworth similarly indict a ‘crisis model’ approach to viewing social and legal problems in favour of one that interrogates discourses and ideologies of oppression rather than only instances where the violence becomes fatal. For them, it is the everyday, non-countable violence that determines the courses of our respective lives.

To that end, some of us count deaths not because deaths are special, but because they are commonplace. Deaths form part of the ongoing state of things. Although tallying the dead runs the risk of representing the crisis itself, it may nonetheless be a useful indicator of structural violence. For example, the death toll may point to what Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes as racism: ‘the state-sanctioned or extra-legal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death’ (Golden Gulag, 2007: 28). In other words, counting the dead can expose symptoms of the conditions of violence.

Third, we count when we can because we can. After all, there are some things we cannot count. In German, there’s a word called Dunkelziffer (literally: dark figure), which refers to the estimated number of unreported cases. It is one of few terms in a language where everday vernacular drips with racial imagery where the double entendre is especially poignant. So we count to keep track, honour and bury those who we know about, since we know there are those whose names and stories we do not know. Maybe we hope to uncover some metric or key for answering the difficult question of why, even when we know that the most we can do is remember and reflect. Maybe we feel that it is the least we can do, but certainly not all we can do.

Fourth, to commit them to memory while allowing them to shape our present way of being in the world. As we count, we also anticipate. Counting is like traction and movement, away from something and towards something else. What we’re moving toward, that’s the hard question.

Fifth, we count because we have to. If we don’t, who else will?

RELATED LINKS

Read the original article here

Read Eddie Bruce Jones’ blog, here

Read the IRR’s Dying for Justice here

Read the IRR’s Unwanted, unnoticed: an audit of 160 asylum and immigration-related deaths, here

Read a synopsis of the IRR’s conference Catching history on the wing, here

Watch the short film ‘Building on Communities of Dissent’, here

Eddie’s sensitive piece also forces us to confront other troubling statistics and the knock-on effects of deaths in custody. In the Netherlands, a 42-year-old tourist from the Caribbean island of Aruba died in hospital on 28 June, a day after his arrest by the police at a music festival in The Hague. At least 200 people – most likely the majority are teenagers – have been arrested for breaking a ban on public assembly. The mayor had introduced the curfew on the third night of police-community clashes in the inner city neighbourhood of Schilderswijk. The long-term impact of the criminalisation of hundreds of young people following a violent death also needs to be counted.