Leeds Beckett University has set a dangerous precedent by publicly severing its links with Aysha Khanom, founder of the Race Trust, following a Twitter controversy.

At the centre of the controversy that led to the severing of all ties with its adviser Khanom by Leeds Beckett University, which hosts the Centre for Race, Education and Decoloniality, lies an attempt by far-right websites and cultural conservatives to link the use by people of colour of the term ‘house Negro’ to the N-word, though their historical and etymological roots are different, as we set out to explain below. The campaign against the Race Trust, an educational project that mentors young people of colour in Manchester, came after a social media troll, using a false identity and a stolen photograph, targeted Khanom, pretending to be sympathetic to the Race Trust’s goals, but subsequently releasing her private messages to far-right news outlets The Point (run by Turning Point UK) and VoteWatch.

Background to the controversy

The story begins on 14 February 2021, when Professor of Black Studies in the School of Social Sciences at Birmingham City University Kehinde Andrews, and Calvin Robinson, strategy and policy adviser to the Reclaim Party, went on BBC’s Big Questions to discuss whether Britain has made progress on racism. Kehinde Andrews is associated with the Critical Race Theory (CRT) academic field of study, which the British government, following the lead of Donald Trump, has announced it is ‘unequivocally against’. Calvin Robinson, senior fellow at Policy Exchange and apparently currently consultant for the Department of Education, describes Critical Race Theory as pernicious – a form of race baiting that is peddled by anti-racists who are the ‘new racists’. Robinson’s view is that Britain, ‘the most tolerant, the most diverse, multicultural society in the world’, is now post-racial, real anti-racists being ‘colour blind’. In contrast, racists (‘racist grifters’, Robinson calls them) are those who persist in using the language of race in public. In this view he builds on the policy goals of the Reclaim Party, which has been described by a Westminster source as ‘UKIP for culture’. Reclaim was created by Laurence Fox, an actor who has gained something of a reputation for opposing the use of terms like ‘white privilege’ which he sees in personal terms as an assault on him (and all white people) based on their skin colour. Fox also opposes ‘forced diversity’, and in one notorious incident called for a boycott of Sainsbury’s after it announced its support for Black History Month.

Calvin Robinson, like Fox and various government ministers such as Priti Patel and Kemi Badenoch, has also been at the forefront of attacks not just on Critical Race Theory, but on Black Lives Matter. Like Patel and Badenoch, Robinson is from an ethnic minority background, though he objects to being so labelled, saying he is ‘just British’ but if he is forced to a description he would prefer ‘half-caste’ as ‘the most accurate’ description of his identity. All three have come under strong criticism from organisations and institutions campaigning over equality and diversity issues, for using their heritage and identity to bolster their own arguments about a post-racial Britain where a victim mindset, or even cultural deficit, hold ethnic minorities back, not institutional racism or structural barriers.

During this critique, the term ‘house Negro’ has been used on social media by individuals who find the stance taken by these politicians perverse and elitist. But while the term could unquestionably give offence, Leeds Beckett University has gone further, to imply – without spelling it out – that the use of the phrase is racist. What lies at the heart of this recent controversy is the distinction between words that are racist and words that could cause offence, with those now berating the Race Trust equating the giving of offence with racism.

In the BBC Big Questions debate with Kehinde Andrews (and in comments made to the Daily Mail), Robinson described the hurt he feels when people call him out for being a house Negro (or, even more pejoratively, bounty bar or coconut). After the show, the Race Trust (a charity founded by Khanom) tweeted him, asking if it wasn’t a cause of shame for him that some people saw him as a house Negro. And this set off a train of events that led to the removal of Aysha Khanom from her advisory role at the Centre for Race, Education and Decoloniality (CRED) at Leeds Beckett University, despite the fact she personally did not send the tweet, though she did make a comment about Robinson in a private conversation, which he interpreted as aggressive, though claiming that he took it on the chin. The offending tweet had been sent by an employee of the Race Trust, which put out a statement admitting it was ill-informed and that they had taken ‘appropriate action’ against the person who sent it.

More twists and turns

From here the story takes on a new number of twists and turns. These are well documented by Byline Times journalists Sian Norris and Nafeez Ahmed, as well as Troll Zoo, a social media account that specialises in monitoring the creation of false accounts on social media. Read together, these two accounts give some idea of the duplicities involved in the making of a case against Aysha Khanom. In particular, the journalists have revealed how:

* various private communications from Khanom were shared without her consent and placed in the public domain by Point News, the news outlet of the far-right Turning Point UK (whose founder is a supporter of the white nationalist QAnon conspiracy theory and whose mother organisation in the US is allegedly rife with racism). Leave EU’s news website Foxhole, and VoteWatch (whose editor was formerly editor-in-chief of the alt-right platform Politicalite, previously suspended from Twitter for violating hate speech rules) also placed the material in the public domain, despite the fact that private direct messages are generally considered off-the-record and printing them without consent without a good public interest justification is considered a breach of privacy;

* a fake account with an assumed name and stolen photograph was created by a Twitter troll, who sought to compromise Khanom by drawing her into a conversation about Robinson while pretending to want to hire her. Turning Point UK and VoteWatch subsequently published edited and cropped screenshots of these messages, withholding the name used in the false account.

*Right-wing newspapers such as the Daily Mail, the Times and the Telegraph then reported on the affair in sensationalist terms, based only on the facts given by Turning Point UK and Vote-Watch, without reporting on the underhand use of a troll.

The aftermath – learning the lessons

So this was the background to Leeds Beckett University’s decision to sever links with Aysha Khanom, seemingly unaware that Calvin Robinson had told both the Daily Mail and theTelegraph that as a supporter of free speech and a critic of ‘cancel culture’ he did not want the originator of the tweet sacked. He added though, that he was glad that ‘this person had been exposed for what they are’ – though not elaborating on what precisely he felt they were, or what had been exposed. However, in an interview with Sky News Australia, he gave the impression – wittingly or unwittingly – that the offending tweet from the Race Trust had used the N-word about him, which had the effect of bolstering his argument that he was the victim of ‘anti-racists’ ‘hurling racist abuse at people’.

All organisations working for racial justice can draw lessons from the experience of the Race Trust, particularly about the need for greater awareness about dangers posed by far-right trolls, and the need to ensure social media activities do not draw organisations into unnecessary controversies that give far-right news outlets and a UKIP-style party the oxygen of publicity.

However, the issues raised by this campaign and the misleading press reportage go beyond the far Right – as explained in interventions from Professor Kehinde Andrews and Professor Gus John, the latter now representing Aysha Khanom in her bid to get a fair hearing from Leeds Beckett University.

It was Professor Gus John who alerted IRR News to the controversy, shocked to learn that the far Right and right-wing press had taken it upon themselves to define the use of ‘Negro’ and the term ‘house Negro’ as a racial slur – and that a university with a Centre for Race, Education and Decoloniality no less, which has at its disposal various archives, could end up legitimating them. ‘Little did they know’, he adds ironically, ‘that by their actions they have made themselves the subject of a fantastic case study in “race and decoloniality”.’

Amongst other learning points!

Which N word?

‘There are some deeply worrying aspects of the Calvin Robinson/Aysha Khanom/Race Trust Twitter saga’, Gus John told us, ‘not least the designation of the term Negro as “racist”. In this whole affair, no one has said why the term “Negro” is racist, who determined it was racist, when they did so, and when in common English usage – in the UK – “Negro” has ever been used as a racial slur’.

John is correct to point out that the debacle has centred around the notion that Negro and the ‘N word’ are interchangeable, when they have different roots and meanings historically. Right-wing newspapers like the Daily Mail went so far as to write ‘n*gro’ as though the word was too vile for their high-minded racially-aware readers to countenance over breakfast. On the other hand, in other modern contexts such as international football, ‘negrito’ has been used as a racial taunt, to wind players up in much the same way as the ‘N word’ was used in the past. The well-known incident involving the Uruguayan player Luís Suarez and the French (Senegalese) player Patrice Evra, demonstrated that.

But, as the IRR argued in its evidence to the Chakrabarti inquiry into antisemitism, it is vital that we do not shift the meaning of ‘racism’ from the objective to the subjective, to personalise it, allowing it to move from something tangible and subject to prosecution, to anything that gives hurt, offence or discomfort. Or as Gus John simply puts it, ‘the fact that a statement or language used might be pejorative does not make it racist’.

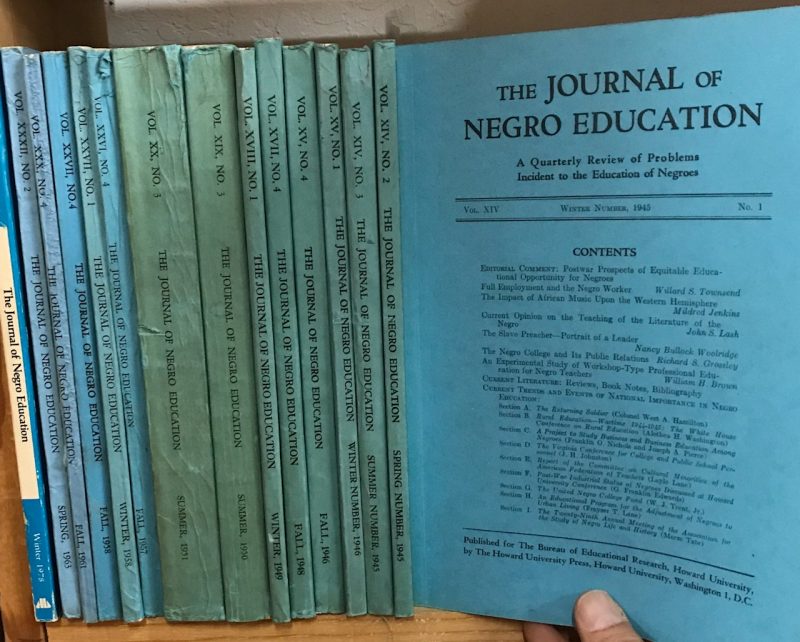

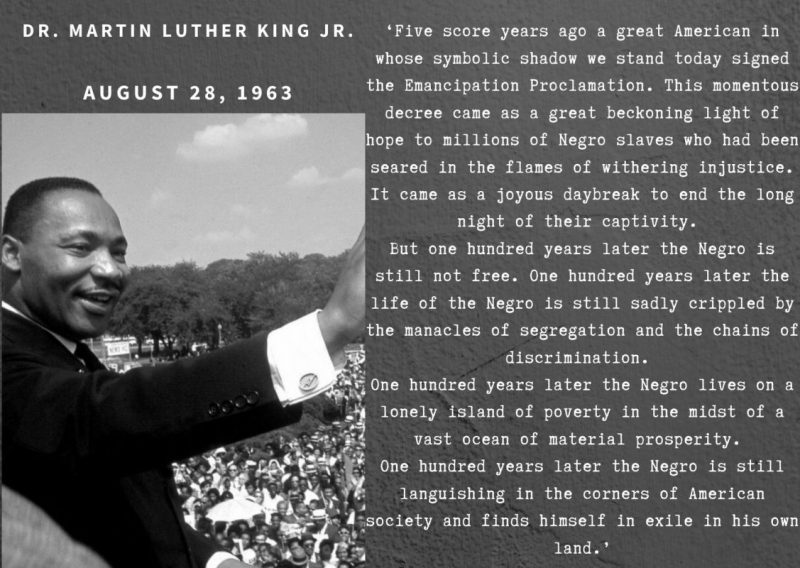

It is of course true that the term Negro is old fashioned and, especially after Malcom X criticised it in the 1960s and introduced the notion of first Black and then Afro-American, it has fallen out of use in the US. In the UK the use of the term Negro gave way in the 1960s to Coloured and later to Black and later to BAME and later to ‘people of colour’. Still, historically, the word Negro was never a racial slur, it was just a word meaning black. It was first used by the Spanish and Portuguese to describe anyone of Black African heritage. And this became the accepted and acceptable term in the late nineteenth century: the American Negro Academy was established in the US in 1897, Marcus Garvey used the word in his famous Universal Negro Improvement Society, Du Bois used the term in his book titles, the Journal of Negro Education was established at Howard in 1932 and the journal still uses that title. The term Negro also continues to be used to describe music – ie, Negro Spirituals (Are we going to see Radio 3 censor the term every time they play Paul Robeson, for fear that Daily Mail readers will faint?) It was a term still used in the US by Martin Luther King in his 1963 ‘I have a dream’ speech. (Are we to see this great speech bowdlerised, to be rendered ineffective, by using asterisks every time King uses the word Negro?)

From Negro to house Negro

Those on the far Right seem to think they are experts on the etymological roots and modern application of the term ‘house Negro’. It is a ‘racist smear to describe a black person either sympathetic to, or envious of white people’, according to VoteWatch editor Jay Beecher. And for Robinson, who believes that ‘anti-racist’ equals ‘racist’ and that the constant focus on race is divisive, it is a form of race-baiting and those who use it must be exposed ‘for the racists they are’.

But as both Gus John and Kehinde Andrews – both professors and both long-serving educationalists – point out, the use of the term ‘house Negro’ is not a racial slur, although when used as part of an understanding of the history of black enslavement, it can certainly make people feel uncomfortable. In fact the term house Negro, which originated as a means of differentiating between those who worked in the house from those who worked on the plantation – ‘field Negro’ – has more of a class connotation than anything else. The differentiation between house and field denoted a class differentiation (during slavery) and could also imply a closer relationship to white society. In a speech about the difference between the house and field Negro, Malcolm X argued that because the house Negro was in a slightly privileged position, not subject to the backbreaking work in the field, he was not best placed to understand the severity of the system. In his open letter to Leeds Beckett University, Kehinde Andrews pointed out that ‘Essentially, it is a recognition of class distinctions in Black communities, that there are those who are slightly better off and therefore might not understand the problem of racism.’ Yes, it is a term that can make people uncomfortable, but that is the point as it encourages an approach that ensures ‘we are accountable to the broad range of Black experience, and not just our own’.

Of course, this is also what lies at the heart of the matter – for collectivism and accountability are anathema to Calvin Robinson’s cultural conservativism. In the final analysis, Leeds Beckett University, in terminating its relationship with Aysha Khanom and issuing a statement that ‘strongly condemns the use of racist language’, has come down firmly on the side of those far-right and right-wing forces that, for whatever reason, conflate racism with the giving of offence and delight in showing up anti-racists as the ‘race offenders’, particularly if they are people of colour.

We contacted Leeds Beckett University, whose spokesperson said ‘The Twitter discussion referenced does not accurately reflect the sequence of events; the timing of our decisions; or the reasons, that we provided to Ms Khanom, for our actions. We published our response to Professor Kehinde Andrew’s open letter on the university’s website.’

Thank you for this insightful and helpful article. I am informally advising an individual who has been reported to their regulatory body for captioning a video on TikTok with the same words and was reported by 4 white people on 4 consecutive days. I would be extremely grateful if you could keep me updated as regards developments in Ms Khanom’s case, in the light of this.

You should not hyperlink to the dodgy sites but just use plain text links to avoid any Google ranking benefits to them

Hello and thank you very much for your comment. We have removed those links.

Thanks Liz for such a clear explanation.

I understand that Ms. Khanom is attempting to persuade an employment tribunal that the terms used are an integral part of critical race theory and anyone who espouses CRT would be expected to use them.

I am the editor of Minority Perspective, a news service for BAME communities in the UK and I saw this coming over ten years ago.

https://minorityperspective.co.uk/2010/06/30/black-councillor-is-convicted-of-racism-is-this-the-end-of-racism-as-we-know-it/

This is what happens when the oppressor gets to define the terminology of oppression, and people of colour have allowed this to happen to our destruction.

For many years the mainstream media has used the white working class argument to dilute and distract debate about racism towards people of colour.

https://minorityperspective.co.uk/2011/05/24/white-victimhood-the-new-racism/

Now, with the rise of cancel culture, another sinister trend which serves to stifle debate, it will not be long before using the term white supremacy will be seen as racist.

https://minorityperspective.co.uk/2021/06/18/the-cancel-culture-con/

Please pass on Aysha Khanom my details at editor@minorityperspective.co.uk

We must also keep in touch about these matters as the need for a strong, independent black media network is more prevalent than ever.

A useful narrative showing anti-racist anomie.The ascribed status of minority groups in the UK reflects the need to overcome further cultural relativism and prevent it becoming another example of primary deviance. Well done.

What no one is also noting here is that Khanom has been ‘cancelled’, although I thought it was supposed to be the likes of Robinson who complain that such ‘cancellation’ is supposed to happen to them.