The director of the Institute of Race Relations calls for the arts to take a stand for human dignity.

Europe is divided, split between its image of itself as the continent of the Enlightenment and humanitarian values, and its shadow-image as the ‘Fortress Europe’ which sets its face like flint against migrants and refugees. In order to protect our people from them, those ‘unwelcome guests’ from impoverished and war-stricken continents, those aliens with different religions and customs, our leaders have turned the 1951 Refugee Convention, which is a humanitarian instrument, into a tool for managed migration. They have fortified Europe’s external borders with the latest technology and surveillance equipment and created vast kingdoms within the civil service for the processing and detention of asylum seekers. Based on the philosophy of deterrence, the idea is to create a system so harsh and unwelcoming as to deter all but the most desperate. The result beggars belief for a continent that prides itself on superior Enlightenment values. Seas that have turned into vast graveyards. A welcome that resembles the concentration camp. A process of removal that is not only cruel and arbitrary, but a destroyer of human dignity. An archipelago of battlements and internment centres across Europe and North Africa that generates huge profits for private security companies whose executives daily dine out on the fare of human misery.

In the previous century (and in a different context), two Jewish scholars, Hannah Arendt and Zygmunt Bauman, set out to understand the social, political and economic factors that led to the Holocaust. Both scholars linked Hitler’s crimes, particularly the Final Solution, to the rise of modern bureaucracies which seek optimal solutions, subordinating thought and action to pragmatism and efficiency, reducing individuals to functionaries of a bureaucratic hierarchy, so that officials, conditioned to follow orders, lose the ability to function and think as moral individuals.[1] Occasionally we get a glimpse of the ruthless bureaucratic and increasingly totalitarian systems that constitute our policy frameworks for migrants and refugees in media reports that detail the morally ambivalent and repellent behaviour of the personnel who staff these systems. The Swedish immigration staff who celebrated the deportation of sick children with coffee and cake, and, in one case, champagne. The British Home Office officials who sought to incentivise immigration officers by rewarding them with gift vouchers, cash benefits and extra holidays if they were successful in thwarting asylum seekers’ appeals against removal. The guards at the detention zone at Zaventem airport in Brussels who separated a pregnant Afghan woman from her husband and left her in a cell for ten hours without food or water, and refused to call an ambulance when she miscarried. The recent allegations about the actions of coastguards in Greece, in an incident which led to the death of at least eight children under the age of twelve, and three women, say it all. Survivors allege that the coastguards’ response to their boat, which had broken down off the island of Farmakonbis, was to try and push it back into international waters by tying a rope to the bow of the ship and towing it away so fast that the boat was ‘bouncing this way and that, like a snake across the water’, until it broke up and capsized. This is how the children and women died in a case, that if proved, constitutes not a terrible tragedy but a state crime that holds a mirror up to Europe’s supposed superior Enlightened values. For the most humble fisherman, in the most remote area of the world, understands the ancient duty to safeguard life at sea and, as such, he is superior in wisdom and moral outlook to the Greek coastguards who, in pushing refugee boats back to sea, did so in the confidence that, in the eyes of officialdom, they were doing no wrong; on the contrary, they were ‘following orders’.

At the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) in London, we have been documenting the structural violence of Europe’s asylum and immigration systems for the last thirty years. Over the last three years, our researchers have collected information on at least 125 deaths that have occurred, not at the border, not as the result of boats capsizing in the Mediterranean, but inside Europe’s asylum and immigration systems. Few people outside the human rights community know that there is currently an epidemic of suicide attempts inside detention centres. Physical and mental strain is exacerbated by the arbitrary nature of decision-making and the legal limbo of lives lived on the margins and in the shadowy depths of society. Poor detention conditions and denial of proper medical care have played a large part in these deaths, which include dozens of suicides. After Mohammad Rahsepar, a 29-year-old Iranian torture survivor, committed suicide at the Würzburg asylum camp in Germany, his friends issued a simple statement, saying he hanged ‘himself from the window with his bed sheets and ended his struggle to find a way to be able to live with dignity in a human society’. Amongst others who have taken their lives after receiving a deportation order, father of two Alain Hatungimana committed suicide in the hope that his children (who had already lost their mother in the civil war in Burundi) would, as orphans, be allowed to stay in the Netherlands. Another father who took his own life was Rexhep Salijaj, who had been separated from his wife and five children, during the war in Kosovo. His son now ran a successful business in Brussels, but the Belgian law on family reunification was such that he was not allowed to stay in Belgium. He could not bear to be separated from the family again and chose to commit suicide.

Why do we count these deaths? ‘Counting’, according to Australian scholars Leanne Weber and Sharon Pickering, ‘is about finding a “trace of life” that can be recorded, and this trace reveals the structural violence of the state’. When it comes to suicide, they write, the authorities reduce suicides to individual factors.

‘Complex chains of causation are absented, and the context of the hopelessness of detention is thereby erased’. Pickering and Weber conducted an autopsy of fatalities of migrants and asylum seekers in Europe, Australia and North America, in order to ascertain the chain of responsibility for deaths. Like Leanne and Sharon, with whom we work closely as associates of the Border Crossing Observatory at Monash University, the IRR is trying to trace the circumstances in which detainees die. Some have died, such as the 29-year-old Malian Mamadou Kamara, (known to his friends as Zoto), through direct state violence. Kamara was severely beaten and died of a cardiac arrest triggered by intense pain, after attempting to escape the Safi detention centre in Malta. Others die also in pain, denied proper health care and medication – from chronic asthma, epilepsy, hepatitis, cancer, heart complaints, HIV, for instance. One such was Zelimkhan Isakov, a torture survivor from Chechnya, who died in physical stress and mental despair after being held for several months in a police cell in Vienna.

And the violence that asylum seekers and irregular migrants suffer is increasing due to the ruthless eviction of the homeless from the makeshift refugee camps that are springing up in every major city of Europe. From despair has come resistance, and each one of the 125 deaths we have recorded has been marked by some kind of protest. These protests, in their turn, are met with police force; using batons and tear gas, they come to evict the refugees from the camps. This leads to more injury, of people already physically weakened, sometimes by hunger strikes, and always by physical and psychological pain.

What more can we do, both at Europe’s external and internal borders, to protect human life and human dignity? Groups like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and also the Council of Europe are constantly issuing press releases and urgent action alerts, reminding governments of their responsibilities under international law. But perhaps it is time to go beyond denunciations, and look at proactive legal interventions. There is a legal term ‘depraved indifference’ which refers to conduct that is so wanton, so callous, so reckless, so deficient in a moral sense of concern, so lacking in regard for the lives of others, and so blameworthy as to warrant criminal liability. Surely Europe’s approach to asylum and migrants now embodies ‘depraved indifference’?

But it is not just what we are doing to migrants and asylum seekers that should galvanise us.  Our treatment of those without papers is the mirror we should hold up to ourselves. In the reflection, we will not only see the macabre ways in which state power and institutional power operates in our societies, but also how our market-driven and celebrity-oriented culture, by encouraging consumerism and envy, drives us away from values based on collectivity, intellectual curiosity (about the inter-connectedness of the world, and hence the reasons for refugee flight) and empathy for the Other. The way in which refugees and migrants are demonised and dehumanised in the media has created a hostile, racist climate in which those of us who try to fight for a Europe underpinned by humanitarian values are derided as weak-minded and unpatriotic individuals, and where those whistleblowers who seek progress, and act out of conscience to expose immoral behaviour, are quickly excommunicated, turned into outsiders, even criminalised. We, in human rights and anti-racist communities, have all the evidence and stories, but our data and reports too often gather dust on the shelves of EU bureaucrats. And even when the evidence of human rights abuses is reported by journalists, the information shocks only for a moment. It is quickly forgotten. For this is the nature of a communication society based on 24-hour news and sensationalist media frameworks.

Our treatment of those without papers is the mirror we should hold up to ourselves. In the reflection, we will not only see the macabre ways in which state power and institutional power operates in our societies, but also how our market-driven and celebrity-oriented culture, by encouraging consumerism and envy, drives us away from values based on collectivity, intellectual curiosity (about the inter-connectedness of the world, and hence the reasons for refugee flight) and empathy for the Other. The way in which refugees and migrants are demonised and dehumanised in the media has created a hostile, racist climate in which those of us who try to fight for a Europe underpinned by humanitarian values are derided as weak-minded and unpatriotic individuals, and where those whistleblowers who seek progress, and act out of conscience to expose immoral behaviour, are quickly excommunicated, turned into outsiders, even criminalised. We, in human rights and anti-racist communities, have all the evidence and stories, but our data and reports too often gather dust on the shelves of EU bureaucrats. And even when the evidence of human rights abuses is reported by journalists, the information shocks only for a moment. It is quickly forgotten. For this is the nature of a communication society based on 24-hour news and sensationalist media frameworks.

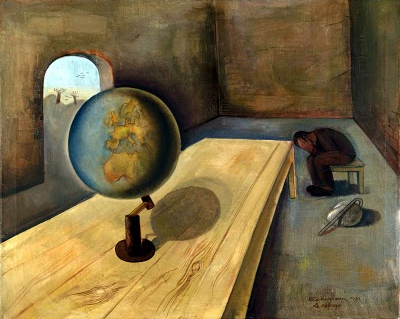

What we face today is the challenge of non-listening, non-seeing, non-feeling. The Pope, in his open-air mass at Lampedusa, held against the backdrop of the hulks of shipwrecked migrant boats, described this as ‘the globalisation of indifference’. To be seen and heard we need a new vocabulary, a syntax to shock people out of complacency. We need to search for new allies – perhaps film-makers, performance artists, dramatists, visual artists who can take our raw material, and amplify our data so that the truth of our appalling treatment of refugees and migrants becomes a ‘revelation that must be heard’.[2] Because art has the power to strip back, to mine down deep below the surface of things, or to concentrate through abstraction, it can challenge structural violence and societal indifference. For ‘Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.’[3]

Liz Fekete is director of the Institute of Race Relations and author of A suitable enemy: racism, migration and Islamophobia in Europe.

RELATED LINKS

This article was first published in BANG Feministik Kulturtidskrift

European Council on Refugees and Exiles

Read a Channel 4 News story: ‘Left to die in British detention: who was Alois Dvorzac?‘

Great article, Liz! So impressed with what you all at the IRR are continuing to do.