There is much to commend in No Place to Call Home, a potted history of Gypsies, Roma and Travellers in the UK and Ireland, but its reliance on police sources is worrying.

There is much to praise in Katharine Quarmby’s No Place to Call Home. She capably describes the structured state and institutional racism that Gypsies and Travellers encounter, and relates their history to the waves of government legislation that abandoned the needs of its poorest communities for those of the market. In the 1800s nomadism faced encroachment from Enclosure, which privatised much of the land traditionally used in Gypsy and Traveller economies. A heightened culture of suspicion grew around those who refused to give up their old way of life until, in 1960, the government introduced the Caravan Sites and Control of Development Act, deciding once and for all to sweep Gypsies and Travellers off the roads and into houses. This rendered it illegal for them to use the majority of their traditional stopping places, making a virtual impossibility of Travelling. This was essentially forced assimilation.

Government policy had now provided the basis for the hounding of Britain’s remaining Gypsies and Travellers – with their right to pitch camp now legally removed, they were prey to the machinery of local politics wherever they tried to make home. One of No Place to Call Home’s strengths is its relaying of forgotten stories of the often-brutal battles that had to be fought against local authorities bent on eviction, in many instances either egged on by, or working at the behest of, a local media that scrutinised the living conditions and behaviour of Gypsies and Travellers: the calls to ‘exterminate the impossibles’ and systematic multiple evictions of Irish Travellers in Birmingham 1967; the attempts of Walsall councillors, in the wake of Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, to send home Irish Travellers while allowing for ‘traditional [read English] Gypsies’. Locals were told time and again, by the press and by politicians, to feel personally pick-pocketed by ‘scrounging’ cultures, vagrants and beggars, ‘human scrap vultures’. Local authorities, whether unwilling or unable to provide for Gypsies and Travellers, instead tacitly supported and empowered a segregationist Nimbyism among the settled community.

Quarmby clearly recognises the systemic nature of anti-Gypsy politics; she understands that the battles for a place to live at Dale Farm and Meriden are the result of decades of anti-Gypsy government policy that has given the Travelling community two ‘options’ – assimilate or be segregated. In seeing the root of social injustice in the word and deed of government, Quarmby guides us around some of the myths often used to distort the public’s view of Gypsies and Travellers. Her work addresses and puts paid to the slogan, popularised by then-Tory leader Michael Howard, that there is ‘one rule for Travellers and another for everyone else’. While Howard’s adage conveys the impression that Gypsies have been given ‘special handouts’ and ‘special treatment’, Quarmby points out that all they have received is special punishment and successive waves of criminalisation.

Blind spots

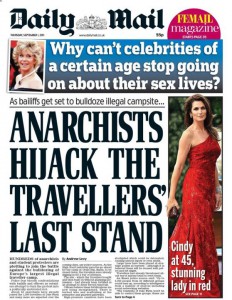

The trouble, however, is that while Quarmby recognises this criminalisation, her view of who is to be considered criminal is sometimes guided by police and local authority sources. Her research took her to Dale Farm, about which she reported on location for The Economist in the years leading to the eviction in 2011. This eviction, billed for months as a showdown between the government and ‘Europe’s largest illegal camp’, made front-page news in the daily newspapers, and live rolling coverage on BBC News 24 and Sky News. In her account of the days leading to the public battle between residents and police, Quarmby follows the lead of the tabloid press and scrutinises the actions of leftwing activists. Travellers, supported by a network of activists, chose to resist eviction, a decision which put them at odds with Essex police. According to the police and the local authority, these activists, ‘extreme anarchists’ whose ‘aim is to cause havoc’, were there to antagonise the police. It was not years of campaigning by the press and local politicians, nor the decisions of Essex Police, that had set the massive scale of the eviction, but the presence and behaviour of these activists. This line, which absolves the local authority and Essex Police of responsibility for the decision to go in, was duly adopted by the national press and is echoed in No Place to Call Home.

Up to this point, Quarmby has criticised those sections of the press that habitually attack Gypsies and Travellers, but at Dale Farm she seems blind to her relatively powerful role as a member of the media, failing to resolve the tension between the responsibilities of the advocate and those of the journalist. As activists began to treat the press, and therefore Quarmby, with suspicion (later vindicated), she turned on them. At this point in her narrative her style of writing shifts, her tone becomes much more sarcastic, even tabloid. She sympathises with the vindictive shaming tactics that the rightwing press employed: ‘exposés about members of the activist community’, published in the Daily Mail, Daily Express, Telegraph and the London Evening Standard, are, to her mind, ‘funny’. In her attempt to rubbish the activists at Dale Farm she adopts the frameworks of the same reactionary press that creates and disseminates anti-Gypsy and Traveller racism.

Up to this point, Quarmby has criticised those sections of the press that habitually attack Gypsies and Travellers, but at Dale Farm she seems blind to her relatively powerful role as a member of the media, failing to resolve the tension between the responsibilities of the advocate and those of the journalist. As activists began to treat the press, and therefore Quarmby, with suspicion (later vindicated), she turned on them. At this point in her narrative her style of writing shifts, her tone becomes much more sarcastic, even tabloid. She sympathises with the vindictive shaming tactics that the rightwing press employed: ‘exposés about members of the activist community’, published in the Daily Mail, Daily Express, Telegraph and the London Evening Standard, are, to her mind, ‘funny’. In her attempt to rubbish the activists at Dale Farm she adopts the frameworks of the same reactionary press that creates and disseminates anti-Gypsy and Traveller racism.

There was, of course, criticism of activists’ tactics from some among the Gypsy and Traveller community, who wondered if the scale of the showdown and the confrontational tactics might do their cause more harm than good. But, as Quarmby acknowledges, the residents of Dale Farm themselves appreciated the unprecedented act of support. So why does her language often invert the balance of power, making aggressors of those defending Dale Farm, and victims of the police force? In a role reversal, we are told that ‘Dale Farm was now being policed’ by activists who ‘never took responsibility for the threat of violence issued by certain among their number’. Meanwhile, she allows the police force to justify its own violent tactics. Quarmby quotes at length and unquestioningly from a police source claiming that the eviction ‘involved the use of Tasers as a form of defence against any weapons on the site’. Defence against what? Police fed intelligence to the media (loyally reproduced in No Place to Call Home), that Travellers and activists had constructed makeshift ‘flamethrowers’ and ‘made a number of devices that look like a ball of metal nails’. This, according to Essex police, made necessary the use of ‘less lethal rather than non-lethal’ force. Yet later we are informed that, ‘Despite the police intelligence about weapons at the site, no guns were ever found. There were no booby-trapped walls or petrol bombs.’ Police briefed the media with intelligence, later found to be baseless, to justify the use of force – where have we heard that before?

Quarmby fails to evaluate her relationship (as a journalist for the national press) with the police force – she never confronts the contradiction between relying on its word as a source of information and holding it to account for its failures and apparent deceptions. This is her blind spot. Because of this failure, the police have once again been able to ensure that their account and their prerogatives are recorded as truth.

Thanks for this. It is an excellent review which is balanced but also critical of the author. It reveals a lot about how public opinion about the Roma is shaped through the control of information in the media.