On Wednesday 14 March, fifteen anti-deportation activists go on trial at Chelmsford Crown Court for endangering airport security at Stansted airport. IRR News interviewed author and academic Luke de Noronha (LdN), spokesperson for the End Deportations campaign, about the case.

IRR News: Who are the Stansted 15, and what was the purpose of their action?

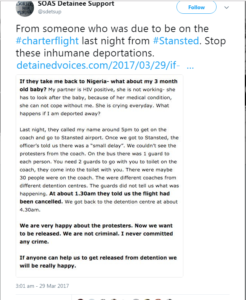

LdN: The Stansted 15 are a group of activists from End Deportations, Plane Stupid and Lesbians and Gays Support the Migrants who prevented a secretive charter deportation flight taking off in March 2017. By chaining themselves to the plane, and lying on the tarmac for over ten hours, they prevented the flight from leaving. The activists knew some of the people booked on the flight, including a lesbian woman who was being threatened by her ex-husband in Nigeria, a man whose family had been killed by Boko Haram, and two young men who had lived in the UK since they were children.

IRR News: Do you know what happened to the people who were due to be deported on that flight?

LdN: Unfortunately we don’t know what happened to everyone who was booked on the flight – but this action allowed several people to remain in the UK. There was one man who was supposed to be on the flight and who was able to return to his partner and be present for the birth of his child. I recently wrote a piece about a young man who was booked on the flight. He was deported last month, but the action gave him time to have another go at appealing. It’s just such a shame the odds are so heavily stacked against migrants in this position.

IRR News: Tell us a bit about the defence campaign and its activities.

LdN: I’d recommend your readers check out the End Deportations website and do what they can to support the Stansted 15 defendants. There will be a show of solidarity on the first day of the trial in Chelmsford. Of course, the activists took this action because they are profoundly concerned about the UK’s brutal immigration regime, and so this is a time to reflect on the reasons for their action. End Deportations is a nascent organisation which is about more than this criminal case. It’s an incredibly hopeful and vital movement. So, yes, people should support the Stansted 15 in whatever ways they can (see you in Chelmsford). But this is broader, it’s about the kind of world we want to live in and the things we’ll let the government do in our name. Hopefully this case draws attention to the brutality and injustice which lies at the heart of the UK’s immigration regime, and can create new space for those who want to end deportations and fight for a world without walls, cages and borders.

IRR News: The defendants were originally charged with aggravated trespass, an offence triable in the magistrates’ court. Later, a terror-related charge of endangering airport security was added, which carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. Do you know why?

LdN: No, I don’t, but the CPS seem to be trying to make an example of these activists. We’ll have to see what happens, but this reliance on discourse and law surrounding ‘terrorism’ reminds us how plastic, capacious and useful the notion of ‘terrorism’ can be for the state.

IRR News: Do charter flight deportations present particular problems over and above those carried out on ordinary commercial flights?

LdN: Yes they do. Charter flights are operations which rely on massive enforcement sweeps to detain certain nationals and thus fill seats on the plane. Migrants lack appeal rights and access to legal aid, and so these sudden enforcement sweeps leave people with no time to make their cases. Timing is central to immigration control. The Home Office slows down time to encourage people to ‘depart voluntarily’ – through denying them rights to work or detaining them indefinitely – but then speeds up time to enact removal. For migrants booked on charter flights, there is simply not enough time. Some people booked on charter flights are only told about it a couple of days before. Again, this is perfectly legal given the draconian nature of UK policy.

With charter flights, it’s not only that people have no time to appeal or to prepare themselves for deportation, it’s also that the flights themselves are notoriously violent, and this is a product of their being private and secretive. On a commercial flight, there is at least some public scrutiny. Whereas on charter flights, if someone tries to resist their removal, the escorts can use many different techniques to enforce compliance, including body restraints and physical violence. It’s actually distressing to even think about. I’ve heard several accounts from people deported on charter flights and there is something grotesque about people in their final moments in the UK, resisting, screaming and shouting, and yet being immobilised and straitjacketed, literally, by up to six escorts privately employed by companies like Tascor.

Of course, there’s a racial element to all this. Independent reports found that Jamaicans and West Africans were inordinately restrained in body belts on charter flights, often with no clear reason why. Deportees have also reported racist abuse on some of these flights. But I don’t want to overstate it here. Charter flights might be the sharpest end of the immigration regime, and they do present some specific violations of human dignity, but commercial flights are not all rosy. Jimmy Mubenga died on a commercial flight. Again, it’s hard to even think about Jimmy Mubenga. A man who was being exiled from his partner and children, a man who died being restrained by escorts who had sent racist texts to one another, escorts who were using a technique called ‘carpet karaoke’.

I’ve met many people who have been deported on commercial flights, and in the end it is the finality of forced separation from friends and family that is paramount. The system itself is violent, brutal and wrenches people from their homes, communities and families. Charter flights are grotesque. But the problem won’t go away if we get an end to charter flights.

IRR News: What would you say to the argument that those being deported have either committed a criminal offence or have no permission to be in the UK, and have been able to present all their reasons for staying to independent judges before being removed?

LdN: Well there a number of things to say here. Firstly, this argument relies on the belief that the UK’s immigration laws themselves are fair. It’s not much use having access to an independent judiciary if the laws themselves are unjust. In the UK, having lived in the UK for many years, having family in the UK, having British children, having studied or worked here for many years, being married to a British citizen, having a real fear of persecution in one’s country of origin, none of these things guarantee you can stay. And it is getting worse. So the UK’s immigration laws don’t just exclude serious criminals and sojourners. Law and policy work to exclude those with really compelling reasons to move and to stay. That’s the first thing: the laws are not fair or just; the system is designed to expel as many migrants as possible, whatever their stories.

But even if immigration laws were fair, decided through transparent and inclusive democratic processes, migrants do not have access to justice. With legal aid cuts and the massive slashing of appeal rights in the past few years, most migrants simply do not get the chance to be heard by an independent judge. Some people represent themselves, and many don’t get to see a judge at all. So the independent judiciary has nothing to do with many of these cases. This is about the power of the executive, the Home Office, forcing people out in legally questionable circumstances. Migrants find it really hard to win cases on the basis of human rights law and the Refugee Convention. People are separated from their friends and families without having had the chance to make a proper case. Charter flights – which encourage the Home Office to fill as many seats as possible – exacerbate these problems for migrants trying to access justice.

Finally the issue of ‘criminal offences’ is important, because the association of migration with criminality is central to how these policies gain legitimacy and explains why non-citizens can be detained in prison-like conditions, in detention centres near airports, without time limit, simply for lacking the correct immigration status or for having been convicted of a minor crime, often years ago. Non-citizens are more likely to be criminalised for drugs offences – usually crimes of poverty – and for fraud and forgery offences, which in practice means immigration crimes, like using a false document or ‘illegal working’. And many of these ‘foreign criminals’ are not very ‘foreign’ at all, but feel as British as you and me – having lived in the same neighbourhoods and attended the same schools as their British friends. These are not the monstrous criminals of the Daily Mail imaginary.

It’s important to tell different stories and make injustice visible. These activists did that with their action, and I thank them for that. They had seen these policies first hand, seen the human damage of all this. They think, like me, that most British people would be disgusted if they knew more about these practices, and more about the lives of those who are illegalised, detained and deported in their name.

IRR News: There has been quite a lot of publicity lately about unjust deportations, particularly of homeless EU citizens, which the High Court ruled to be illegal, and of African-Caribbean pensioners who have lived in the UK for over fifty years. And recently the Supreme Court ruled ‘deport first, appeal later’ deportations illegal. Do these developments mean that fewer unjust deportations are taking place, lessening the need for campaigns against deportation?

LdN: These cases you mention are important, and I’m glad that the Home Office is no longer able to deport European rough sleepers, many of whom were working and still could not afford rent. I’m also glad that ‘deport first, appeal later’ was ruled unlawful, which gives some migrants a chance to have their appeals heard in the UK. But these do not change anything substantively. There are still the same amount of beds in the UK’s detention centres, and they will continue to be filled. While legal challenges and campaigns are able to frustrate the Home Office, the architecture of racialised border violence remains. In other words, families are still being separated, people are still being detained indefinitely, and our friends, colleagues and neighbours are still being banished to forgotten homelands and places where they will face persecution. So there is a lot more work to be done, and this action was definitely part of that conversation.

IRR News: What can direct action protests such as this achieve, given that charter flight deportations are now routine, from the UK and from many other European countries?

LdN: Well they stopped people flying that night. This gave some people time to make a case and to stay in the UK. And the action drew attention to the violence of charter flights and the UK’s deportation regime more broadly. There is value in that. Perhaps the extent to which these charter flights are now routine in Europe is the extent to which we need to interrupt these forms of state violence. There are different ways of doing that, ways that can complement one another.

You know that people have been writing about these things for many years, and those of us in the migrant sector have long been trying to draw attention to the brutality of the system. I myself have written articles, written to MPs, found people pro bono representation, and yet still watched them deported. I have seen people struggle with poverty, isolation and homelessness when they arrive back ‘home’. It’s devastating. So we have to try and do something.

Most importantly, we follow the lead of those subject to indefinite detention and deportation, like the women currently hunger striking in Yarl’s Wood. The most important people in this conversation are those subject to the violence. Borders separate people from their homes; globally, borders kill and let die on an unimaginable scale. This action was about standing together to resist this, a struggle we all need to get behind in these violently anti-immigrant times.

Related links

This is very helpful for talking with people about the trial. Thanks.

An interesting interview article. I’m completly for ensuring the rights of individuals, however this article gives no insight into the specific demands or changes or challenges to which laws and regulations these activists are campaigning against.

On the outside it looks like creating a public following based on tales and a few individuals views.

Please can you give some concrete statistics and valid reasons against these practices, before you whip up public support for something.

How many of these flights have taken place

What percentage of the people had had some form of legal aid

What percentage had committed crimes

What was the average time the people had remained in the UK after being informed they would be deported

These types of facts would give your campaign more validity. As it stands the 15 people look like they carried out these actions just to cause disruption.