On the launch of the young people’s oral history project exhibition ‘Activating Newham Community & Activism 1980-1991’, Jasbir Singh writes about his experiences and the seminal work of the Asian Youth Movements in the 1970s and 80s.

Where did the Asian Youth Movements come from?

The Asian youth movements (AYMs) arose in the late 1970s and continued into the mid- to late-1980s across the country. The late 1970s saw the children of post-war migrant populations from the Indian sub-continent, reach adulthood. And it was they that formed the AYMs and became their supporters. Whilst many members were of college age, there were individuals who were as young as 15 and others in their late 20s, who may have had experience of organising from political parties or the workplace.

The broad age range of members highlights a key concern of the AYMs: they wished to create organisations that represented and took up the concerns, the grievances, of young south Asians and their families. In a sense they were organisations of youth but not simply for the youth. They advocated for their communities as a whole and the issues that impacted them. They were responding to the climate of racism they faced, in a period of rising unemployment caused by an economic downturn that led to the decline of industrial Britain. This climate included attacks on the street, racist and discriminatory policies/practices in housing and the workplace, as well as racist immigration laws. In addition, most of the youth who became future members of the AYMs also faced discrimination and racism in their schools. As such, they could relate directly, to the broader issues which their families and others were facing.

The AYMs originally formed in cities and towns principally across the north of England. These included Bradford, Sheffield, Manchester, but also Coventry, Leicester, Birmingham and London. Others then developed in smaller towns such as Bolton, Burnley, Luton and Watford. In London there were a number throughout the city, the most prominent being in Southall, but there were also smaller AYMs in Haringey and in Newham.

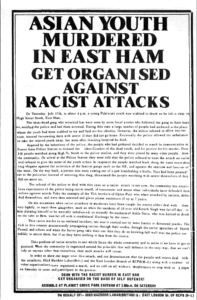

The Newham Youth Movement came into being after the murder of Akhtar Ali Baig in 1980. A group of Asian youth in Newham, who were aware of the AYMs in Bradford and Southall, were spurred on to act using the AYM model. They played a critical and important part in organising a huge demonstration in Newham following Ali Beg’s murder. At the march the Newham Youth Movement adapted the slogan of the children of Soweto: ‘Don’t mourn – organise’.

Community-led and organised

The movements often developed in response to a local event. However, the national media coverage of the resistance in the communities and youth, particularly in Southall and Bradford helped to spread the message of various groups and played a crucial role in inspiring others. Bradford in particular was central in the development of the youth movements across Britain. This was because the AYM in Bradford, did not simply provide a spontaneous response to a new issue but also developed an organised response to a broader attack on their communities. It was the largest AYM and it developed a disciplined cadre of members. Whilst they saw their strength in mobilising locally, the Bradford AYM also saw itself as facilitator for the development of youth movements in other cities and towns.

A continuous development and a real understanding of racism and how it fitted into the broader political landscape was important to many AYM members. As such, study sessions were an important activity and many AYMs produced newsletters to better educate themselves and their wider community. It is important to remember that this was time when there were no laser printers or mobile phones, no social media or google. The only way to contact people was to make a phone call or write a letter; and phone calls were expensive. The journals from organisations like the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) and Race Today also played an important part in providing an understanding and shaping the politics of the AYM members. These were often photocopied and distributed to members to read.

Campaigning and solidarity

As mentioned earlier, the emergence of many of the AYMs was as a response to local events — a racist attack, a deportation, a wrongful racist police arrest or a murder (as was the case in Newham). A number of the local campaigns begun by a local AYM became national with support from AYMs across the country. One such campaign was the Anwar Ditta campaign which highlighted the racist immigration laws which prevented Anwar’s three children, who were in Pakistan, from reuniting with their mother in Rochdale. It was a campaign that won national coverage with its heart-breaking story. AYMs in Manchester, Bradford, Dewsbury, Sheffield and Nottingham worked together.

Challenging racist immigration laws and fighting deportation were huge activities for AYMs which worked together with other campaign groups, such as, the Campaign Against Immigration Laws (CAIL) and the Campaign Against Racist Laws (CARL). A large number of the immigration and anti-deportation campaigns were organised and run together with the Indian Workers Association (IWAs).

Anwar Ditta Campaign:

The Anwar Ditta campaign also highlighted the way that the AYMs put the families at the centre of the campaign to promote the issues, rather than the AYM organisation. The Anwar Ditta campaign also highlighted the ability and strength of the AYMs to organise and build solidarity, and also to empower the victims – in this case Anwar Ditta. I was a member of the Sheffield AYM when we launched a local campaign to bring attention to her case. I still remember the local march that we organised, the thousands of leaflets that we gave out and the impassioned speech that Anwar Ditta gave on the steps of Sheffield Town Hall.

Bradford 12 Campaign:

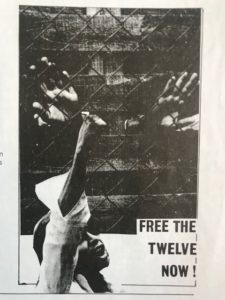

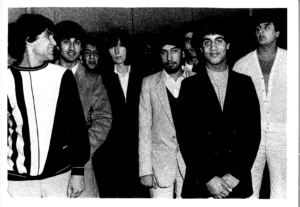

Another campaign that became national, championed by the AYMs was the Bradford 12 campaign. The summer of 1981, saw unrest explode in several parts of the country. There were racist attacks and there was fight back and rebellion. In this background, members of the United Black Youth League in Bradford, who were closely associated with the Bradford AYM, made petrol bombs – ‘in order to be prepared, should the need arise to protect themselves and their communities against the fascists’. These petrol bombs were never actually used.

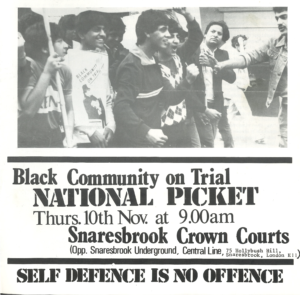

But this didn’t stop 12 youth being arrested a few weeks later and charged with ‘making as explosive substance with intent to endanger life and property’ as well as ‘conspiracy to make explosives for unlawful purpose’. Immediately following the arrests, there was huge support for the young men both from the local community and activists. The network of AYMs across the country mobilised for the campaign. They were also heavily involved in ensuring that there was solid legal defence. The trial of the Bradford 12 brought national attention to the issues of self-defence and conspiracy laws. It was in this campaign that the phrase ‘Self Defence = No Offence’ was coined. It also acted as a national focal point against repressive policing policies and practices towards black people. Another slogan coined during this time was – ‘Whose conspiracy – Police Conspiracy’ referring to the conspiracy charges that the Bradford 12 were charged with.

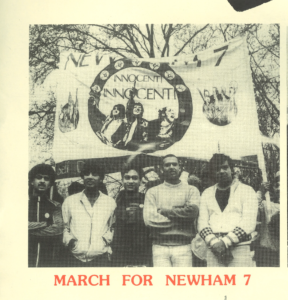

Newham 8 Defence Campaign:

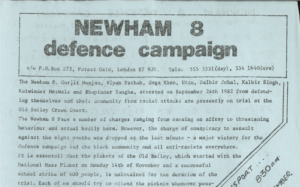

The use of the conspiracy laws was a significant part of the state’s strategy to crush independent and militant black organisations during this period. We saw this strategy also being used in the case of eight youth, in Newham in 1982, who were protecting school children from racist attacks – a case that became known as the Newham 8 and the Newham 8 Defence Campaign.

There had been a spate of racist abuse and attacks in schools in Newham against Asian children. In response, a group of older youths decided that they would protect and walk the children home after school. On one occasion, three white men stormed out of a car and started running towards this group of school children in a menacing way. Thinking it was an attack, the older youth stopped and fought back, only to later learn that these three white men were plain clothes police officers. Eight youth were charged with conspiracy to cause affray. As with the Bradford 12, from the start there was huge support for the young men both from the local community and activists. The Newham 8 Defence Campaign was set up following a community-organised meeting.

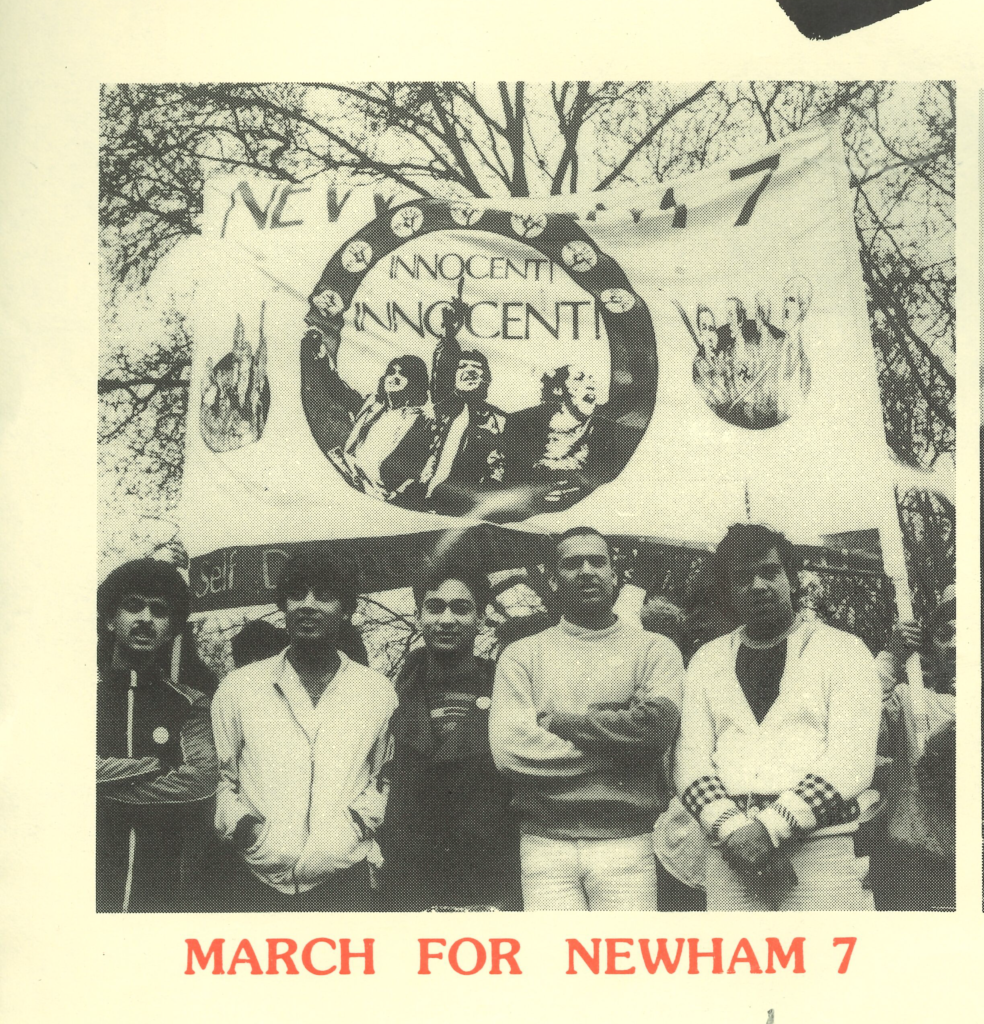

Once again, the network of AYMs mobilised for the campaign and make sure that there was support from across the country. The case of the Newham 8, again, brought to national prominence the issues of self-defence and conspiracy laws. ‘Self Defence – No Offence’ and ‘Whose conspiracy – Police Conspiracy’ were again the main slogans, shouted this time outside the Old Bailey where the trial was held. These are just three examples of campaigns that AYMs took up, other significant ones include: the New Cross Massacre, Solidarity with the Miners and the Newham 7 Defence Campaign.

Building a National Movement

The AYMs made several attempts to try and become a national movement and a national organisation. As mentioned earlier, Bradford AYM saw itself as a facilitator for the development of youth movements in other cities and towns, with a view to strengthen working links. Groups in London also made efforts in this direction. However, the AYMs never achieved a national organisation, in part because of the changing priorities of the different AYM organisations. That is not to say there were not always links between the different AYMs, but they focused on their local issues and sought support for their campaigns from other AYMs as and when required.

Building Internationalism

A national organisation focused on the struggles of the British Asian community was also complicated by the internationalist outlook of AYMs. Whilst focused on Britain and the issues that impacted them and their families, these young people saw a direct connection between the global political context and their own experiences. They were inspired by both the anti-colonial struggles of the previous decades as well as the Civil Rights and Black Power movements in America. At the same time, anti-colonial struggles were still being waged in Palestine, Zimbabwe and South Africa and the youth felt these experiences related to their own. They were motivated by political ideas and strategies from organisations across the world such as the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa, communism in China and other international struggles. The AYMs were outward looking, wanting to make links with groups with similar beliefs in Britain and abroad.

The AYMs did more than just read and learn about these struggles. For example, there was strong support for Ireland’s right to self determination and a number of AYM members made visits to Belfast to learn from and draw closer links with the Republican movement. There was also solidarity with Irish Republican prisoners, with AYM Bradford sending two delegates to the North of England Irish Prisoner’s committee in relation to the imprisonment of Bobby Sands.

The fight of the Palestinian people was another issue taken up in a huge way by the AYMs. In 1982 thousands of Palestinians were massacred in the Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps in Lebanon. Bradford AYM supported the ad-hoc committee against the genocide in Lebanon. In Sheffield, the AYM mobilised to put pressure on members of the local Trade Union who were meeting the Israeli Trade Union Federation. Several other AYMs supported and mobilised for local marches that were taking place at that time against this massacre.

How to struggle for Truth

By the mid-1980s, many of the AYMs were in decline. The state had poured a significant amount of money into youth schemes, education projects, a vast array of cultural organisations, rights organisations and legal centres which resulted in the shift of many AYMs from campaigning to service-provision. Many AYM members took up jobs in these newly created organisations which meant the demise of the former AYMs. New organisations were formed to try and take up the work but their success was diffused.

That the AYMs were only around for roughly a decade does not diminish the huge contribution they made. I would like to end using the words of Gareth Peirce, the solicitor who defended some of the Newham 8 and Newham 7, when she was asked to comment on the Bradford 12 Campaign and the AYMs.

‘It was for many of us the happiest time of our life because we were fighting a war on the same side and when you are involved in that fight, the bonds you make are the strongest bonds you will ever make in your life … we owe to them that line of history that gives us still some hope in saying that whatever the language used, however the false narrative is sustained wherever it is in the world that we are party to the same disgraceful injustice of calling self-defence something different, we absolutely owe it to you our thanks for teaching us how to struggle for the truth.’

Footnotes:

Jasbir Singh is a campaigner and activist who has been involved in many campaigns including, founder of Black consciousness group at Sheffield University (1978-1981), Sheffield Asian Youth Movement member (1981-83) and Campaigns worker/ Managing Committee member at Newham Monitoring Project (1983-1986/1989-1998)

This is a piece based on a speech given at an ‘Activating Newham’ project workshop session on Asian Youth Movements in the 1980s at Rabbits Road Press, London.

Exhibition at Old Manor Park Library, 2 – 29 November, 2019 (Saturday & Sunday only) https://createlondon.org/event/activating-newham/

If you would like to attend the private launch event on 2 November, please email rsvp@createlondon.org