Australia’s inhuman anti-asylum policies may survive the many protests at Reza Berati’s offshore detention death, but change can come through global solidarity in pursuit of justice for asylum seekers, says Leanne Weber of the Border Crossing Observatory at Monash University.

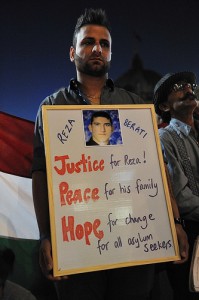

On 23 February Melbourne’s Federation Square filled with people who had come to commemorate the death of a young Kurdish man in the Manus Island detention centre in Papua New Guinea (PNG). Reza Berati was killed during a terrifying outbreak of violence believed to have involved local PNG police and G4S employees, in which many other detainees were also injured.

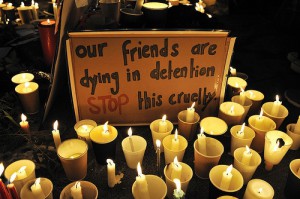

In a spirit of both mourning and peaceful protest, the crowd in Federation Square lit candles alongside photographs of the 23-year-old, displayed signs declaring that refugees were not illegal and were welcome in Australia, and set up shrines dedicated to the memory of all those who had died as a result of Australian border controls. Some carried Kurdish flags. A few carried Australian ones. It seemed as though this moment might bring to a head a longstanding struggle over the soul of the Australian nation.

But how realistic is it to expect that anything good might come from this tragedy? There have been watershed moments in Australian border control before and they have invariably been resolved in favour of even more egregious policies. First there was the refusal by the Australian government in 2001 to allow the MV Tampa to bring rescued asylum seekers to Australia’s shores. These infamous events ushered in the Pacific Solution. Soon after, revelations that government ministers had lied about asylum seekers deliberately throwing their children overboard (the so-called Children Overboard Affair), failed to bring an end to the public vilification of those who arrive by boat, correct the public record, or call to account the ministers responsible. Even the shocking loss of fifty lives in December 2010, that occurred in full view of Christmas Island residents and the Australian media, when a flimsy vessel carrying asylum seekers was dashed to pieces against rocks failed to trigger a wholesale re-think of Australia’s fatally flawed deterrence policies. On the contrary, those deaths and the hundreds of other deaths at sea that followed, prompted an ‘expert panel’ to endorse the deterrence approach and recommend a return to offshore processing that was dubbed Pacific Solution II. The final tipping point was the 2013 federal election, in which both major parties engaged in a race to the bottom which has left in its wake a mix of punitive and secretive border defences that will seemingly stop at nothing to prevent the arrival of asylum seekers.

In the face of concerted efforts to destroy all hope for asylum seekers seeking to reach Australian shores, local human rights campaigners still strive to keep hope alive. In the words of veteran advocate Pamela Curr of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre: ‘I don’t believe in false hope but no one can be left with no hope. We would not be fighting this if we believed that we could not change it.’

The death of Reza Berati and revelations of the horror of the Manus Island detention regime has intensified protest in Australia. Five hundred academics signed an open letter to prime minister Tony Abbott demanding an end to offshore detention and processing; then, as word spread, the letter was re-opened for more signatures due to popular demand. Migration agent Liz Thompson, who was contracted to provide legal advice to Manus Island detainees, violated the terms of her contract and spoke out on national television calling the camp an ‘experiment in the active creation of horror’. Artists contracted to perform at the Sydney Biennale event withdrew in protest over sponsorship by Transfield, the company which manages Australia’s offshore detention camps. And a Baptist pastor who arrived by boat himself as a refugee from the Vietnam War set off to walk from Melbourne to Canberra pulling behind him a replica of the boat on which he travelled, with a message of thanks to the Australian public for the ‘gift of refuge’ he received, and an implicit message about the contrasting treatment of today’s ‘boat people’. Although they continue to express their outrage and spread positive messages of hope and humanity, political activists and refugee advocates know they are swimming against the powerful tide of populist politics. In a widely reported opinion poll conducted just before the Manus Island violence, sixty per cent of respondents said they supported even harsher measures to prevent boat arrivals.

Avoiding responsibility

Academics have contributed to our knowledge of the processes through which governments (and their willing media allies) can control the representation of unpalatable events and withstand even the most authoritative allegations of human rights abuse. The late Stanley Cohen in his seminal work States of Denial, helped us understand how governments are able to deny responsibility for human rights abuses through processes that distort the interpretation of government actions and shift blame to others. In the book I co-wrote with Sharon Pickering on border-related deaths we applied Cohen’s ideas to show how the harm of border control policies can be obscured by a range of systemic factors. These include distanciation, in which complex chains of responsibility make it difficult to connect cause (i.e. government policies) with effect (i.e. border-related deaths); deliberate strategies of demonisation and neutralisation, which represent the targets of harmful policies as threatening and undeserving; and deeply ingrained patterns of authorisation, whereby large sections of the population can be persuaded to accept even the most egregious acts if they are portrayed as necessary in order to achieve some higher goal, such as orderly borders and the protection of national security.

It is easy to see these techniques and processes at work in relation to the death of Reza Berati and the policies that led to his death. While deaths at sea fit into the category described in our book as ‘structural violence’, where the links between border control policies and deaths are not visible, there is a clear and direct link between a death in custody and the policies of mandatory offshore detention, a link which establishes a duty of care on the Australian government. However, well before the facts about the violence at the camp had fully emerged, the immigration minister acted to defend the G4S security company that operates the Manus Island camp and shift blame onto hostile PNG locals and the asylum seekers themselves. Although the minister was quickly forced to retract, this version of events is likely to retain some purchase with a public that has been conditioned to view asylum seekers as dangerous criminals. Moreover, the internal inquiry set up to investigate the unrest has been criticised for its narrow terms of reference and the objectivity of the person appointed to lead it, both of which reflect government attempts to manipulate the account of events. Most politically potent of all, perhaps, is the pernicious argument that deaths such as Reza’s are an unfortunate by-product of tough policies that are necessary in order to avoid the even greater numbers of deaths at sea that would otherwise have occurred. Although it is true that boat arrivals, and deaths at sea, have both diminished significantly since the inception of the current policies, these utilitarian arguments completely ignore alternative ways of achieving a similar end without breaching human rights.

Against this backdrop of government denial of responsibility for border-related harm, and public support for even harsher policies to stop asylum seekers arriving by boat, it is increasingly difficult to find cause for hope. With individual countries like Australia deeply mired in inward-looking and nationalist politics, perhaps the answers are to be found by looking beyond borders in order to open up a global space for legal, political and social action.

Global direct action

The day before this article was drafted a series of twenty large-scale rallies were held, in which organisers claimed to have mobilised more than 100,000 people across Australia to protest a range of conservative policies relating to conservation, minority rights and the treatment of asylum seekers. These traditional methods of democratic protest are increasingly supplemented by on-line petitions that use digital technology to cross borders and tap into sources of opposition to Australian policies from around the world. Transferring ideas for direct action across boundaries is another powerful idea for globalising political action. An inspiring candidate for adoption in Australia is the Watch the Med programme that collates information on migrant vessels in distress while en route from North Africa to southern Europe. Another direction through which international solidarity could be expressed is through the adoption of immigration detainees as prisoners of conscience by campaigning organisations such as Amnesty International, a development which may well have already happened, but of which I am personally unaware.

In the absence of due process protections or access to a national or regional human rights apparatus in Australia, the task of protecting individuals from border-related harm through legal action is very difficult. Individual findings of wrongful detention through quasi-judicial bodies like the Human Rights Commission and Commonwealth Ombudsman have occurred. And High Court action on at least one occasion worked to derail a bizarre proposal from the former government that would have seen asylum seekers arriving at Christmas Island ‘swapped’ for recognised refugees in Malaysia. Political campaigns to introduce a Bill of Rights or some equivalent mechanism have so far been unsuccessful. But despite the limited purchase of human rights in Australia, political debate can still be enlivened by reference to overseas legal judgements that uphold the human rights of asylum seekers and irregular migrants. In the aftermath of the disturbances on Manus Island, it is inspiring to note that courts in both Italy and Greece have ruled that escape and violent resistance by immigration detainees were justified due to the appalling conditions in which they were being held. Even more significant was the ruling by the European Court of Human Rights in 2011 that conditions for asylum seekers in Greece were so abject that returning them there constituted cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, after which several European countries suspended transfers to that country.

Counting and accounting for deaths

Another set of developments which give cause for hope are campaigns to have border-related deaths counted and dealt with under the same sets of rules that apply in other contexts. In our book on border-related deaths, Sharon Pickering and I argued that the process of counting was important in itself as a way of naming and commemorating individual deaths, but was also a step towards properly accounting for deaths by holding governments and other parties responsible.

Having discovered during the writing of the book that no official data sources on border-related deaths existed in Australia, we have since made our database of border-related deaths publicly available through our Border Crossing Observatory website. At the time of writing, the border deaths database contains records of 1493 known deaths since the year 2000. We also launched a campaign via social media to have those deaths that occurred in immigration custody included in the existing national collection of deaths in police and prison custody. This would include deaths in detention such as Reza Berati’s, but would also encompass deaths that occur wherever non-citizens are under the control of government agents, such as during deportation, arrest or offshore interdiction. On the global stage, the International Organisation for Migration is conducting a major international project highlighting the need for international systems to count border-related deaths. The Border Crossing Observatory has been asked to contribute, offering a rare opportunity to raise global awareness about the need to both count and account for border-related deaths.

The developments discussed here may offer only small glimmers of hope when viewed at the local or national level. However, just as the light from a multitude of tiny candles lit up Federation Square in memory of Reza Berati, global solidarity in pursuit of justice for asylum seekers and irregular migrants has the potential to generate political heat and enlighten popular consciousness. In the words of the late Dr Martin Luther King, ‘Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that.’

Leanne Weber is Senior Research Fellow in the School of Social Sciences at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a co-director of the Border Crossing Observatory and co-author, with Sharon Pickering, of Globalization and Borders: Death at the Global Frontier.