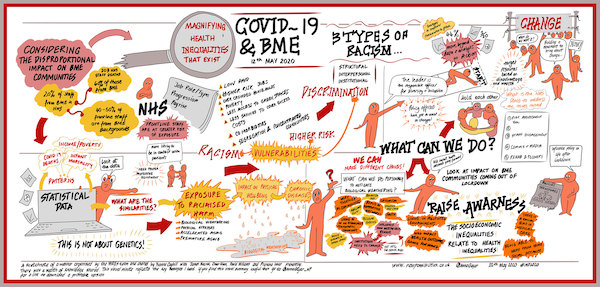

As Public Health England conducts its controversial rapid review into Covid-19 disparities, lurking in the background is a new school of ‘race realists’ whose retrogressive biological arguments must be tackled head-on.

An intellectual current that can be broadly defined as New Right – comprising a number of thinktanks, politicians, journalists, academics and libertarians of various persuasions – is attempting to turn the debate over the disproportionate number of deaths of BME people from Covid-19 into a key battlefield for the normalisation of scientific and cultural racism. Sometimes referring to themselves as ‘race realists’, these New Right opinion-makers argue that race is a biological fact and human differences are the basis of social inequalities.

The anti-racist movement must be on its toes to ensure that their lies have not run round the world before the truth has got its boots on. It needs to prevent them from trivialising our suffering through their attempts to manipulate discussion of personalities, prejudice and patronage, and ensure that any future inquiry focuses on evidence, ethics, and enforcement.

‘We’re only following the science’

In the early 20th century, the Nazis attempted to establish science as the objective basis for the racial hygiene programmes. As I previously argued on IRR News, the ‘race thinking’ of Hitler’s scientists and academics had its roots in the scientific racism of the Enlightenment period and the attempts to biologise human variation. And now this kind of ‘race science is on the rise again’ with a number of discredited academics, researchers and pundits locating themselves in the free market of ideas as free thinking ‘race realists’. Backed by right-wing think-tanks to establish new norms in the discourse about race, including the idea that human differences comprise the basis of inequalities, they espouse a biological essentialist, monogenetic, genetic deterministic, biological nationalism. A nationalism that argues that as biological race differences exist and racial classification has a genetic basis, it is impossible to construct social mitigations for disadvantages. For inequality is, in the final analysis, biologically determined. Inequality exists, they admit, but crucially it doesn’t reflect historical injustice or current social practices but the fact that, deep down, we’re not the same. In this way they pretend to be politically neutral, and only following the science, but by so doing manipulate science to construct imaginary boundaries to social progress. The ‘successful’ nativism of the new populist electoral Right from Trump, to Bolsonaro, Orbán and Johnson also speaks volumes as to the way the arguments of the New Right and the ‘race realists’, with their undertones of white supremacy, are now mainstreamed.

It’s so easy to show how the ‘analysis’ of ‘race realists’ is flawed because it wrongly asserts that the human species comes packaged up in a small number of discrete races, each with its own different traits, and that, as a consequence, there are innate explanations for political and economic inequality. Their ideas are, however, increasingly played out in the heuristics of policy-making to establish a new common sense around programmes to end discrimination and promote equality. For the New Right, equality policies, like any other social safety nets and mitigations, are incompatible with a free market that alone enables social progress, and should be dismantled.

Unpicking the safety nets

The NHS is one social safety net to which the British public remains stubbornly attached. It has always been an anathema to the dogmatic Right, because as Nye Bevan observed, ‘A free health service is pure socialism and as such is opposed to the hedonism of capitalist society.’

The realities of electoral politics have forced the Tory party to reach accommodation with the existence of the NHS. The Right’s desire for full privatisation has had to be satisfied with piecemeal marketisation, and the gradual undermining of the NHS core principle of universality the Conservative party tried to undermine from its inception. Nye Bevan again: ‘One of the consequences of the universality of the British National Health Service is the free treatment of foreign visitors. This has given rise to a great deal of criticism, most of it ill-informed and some of it deliberately mischievous… The whole agitation has a nasty taste. Instead of rejoicing at the opportunity to practise a civilised principle, the Conservatives have tried to exploit the most disreputable emotions in this among many other attempts to discredit socialised medicine.’[1]

Although the NHS has a long history of institutional racism, it was the New Labour government of Tony Blair that strengthened the structural elements, via the NHS (Treatment of Overseas Visitors) (Amendment) Regulations 2004, which first hypothesised the links between immigration, health tourism and the viability of the NHS. Since then, successive governments have extended charges linked to immigration control across the NHS. But it was the hostile environment that nudged the NHS into abandoning the basic tenets of its own convention – leaving British patients to suffer and die as an act of racist policy.

Covid-19 – not tragedy but opportunity

Covid-19 presents the New Right and those who accept its parameters with a further opportunity to undermine the NHS, by using it as a vehicle to legitimise and spread the ideas of the race realists. This is why as soon as concern relating to excess death rates in BME communities surfaced, many right-wing and libertarian commentators came forward in an attempt to reframe the debate in terms of biological inheritance, lifestyle choices, and cultural differences that have no connection to discrimination. It is these differences, they argued, that mean we have more opportunities to contract the virus and have more long-term health conditions which make us more likely to die. Therefore any call to examine the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on BME communities – outside genetic and cultural frameworks – is written off as shroud-waving by the ‘victimhood mob’ and the politically correct ‘inventors of statistical victimhood’, as implied by both Civitas chief executive David Green, writing in the Telegraph, and Wasiq Wasiq, writing for the blog Harry’s Place in defence of Trevor Phillips’ appointment to the PHE inquiry.

The announcement that the proposed Public Health England (PHE) review would be supported by the services of the Webber Phillips consultancy, suggested that discredited race thinking could make a comeback. It looked as though the inquiry would conform to a ‘professionalised’ multi-agency approach that embraces private, state and established Third Sector organisations, thus co-opting or delegitimising independent dissenting voices. And that it would have access to data-driven identification technologies and databases that can replicate racialised stereotypes and reinforce institutionalised prejudices. Moreover, it would include someone with a track record of leading inquiries that found ‘cultural deficit’ within the groups that are ‘failing’ at the expense of the structural determinants of racism. All the elements for a successful whitewash that would obscure the role of institutional racism were in place in the PHE inquiry – but then came the reaction.

Race and reaction – fallacies exposed

Unfortunately for the New Right, while PHE was distracted by public scrutiny following the Webber Phillips announcement, new data and analysis from independent and credible sources began to expose the fallacy of the New Right narrative.

In a University of Oxford and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine study, researchers reviewed health data of more than 17.4 million UK adults and concluded ‘People from Asian and black groups are at markedly increased risk of in-hospital death from COVID-19, and contrary to some prior speculation this is only partially attributable to pre-existing clinical risk factors or deprivation.’ The study co-lead Professor Liam Smeeth commented: ‘It is very concerning to see that the higher risks faced by people from BAME backgrounds are not attributable to identifiable underlying health conditions.’

A study by UCL based on an analysis of NHS data from English hospitals in March and April found that after adjusting for age and region, BME groups were 2-3 times more likely to die with Covid-19. Lead author Dr Rob Aldridge said: ‘Our findings support an urgent need to take action to reduce the risk of death from Covid-19 for BAME groups.’

A study by the Office for National Statistics utilised 2011 census data and binary regression logistic modelling, to control for geographical, demographic, socio-economic (including living arrangements) and health factors (including self-reported health conditions and disability) to identify BME risk of dying from Covid-19. Its data showed that after controlling for age alone, in Britain’s black communities, women are 4.3 and men 4.2 times more likely to have a Covid-19-related death than white women and men. Among the Bangladeshi and Pakistani communities, men are 3.6 and women 3.4 times, and among the Indian community men are 2.67 and women 2.39 times more likely to die. After accounting for age, socio-demographic and self-reported health and disability, Black men were 1.93, Black women 1.89, Bangladeshi/Pakistani men 1.81, Bangladeshi/Pakistani women 1.61, Indian women 1.43 and Indian men 1.32 times more likely to have a Covid-19 related-death than their white counterparts. The ONS concluded that ‘These results show that the difference between ethnic groups in COVID-19 mortality is partly a result of socio-economic disadvantage and other circumstances, but a remaining part of the difference has not yet been explained.’

In fact, when taken together, this body of research evidence discounts the core assumptions within the New Right’s story. Whereas race is irrelevant, racism is not, and it is racism that is likely to be the mediating factor that explains why so many people in BME communities are dying of coronavirus.

Learning from health research in the US

But the nature versus nurture positions may be too crass in any event. We might learn something here from previous studies in the US where health researchers in fields like epigenetics (study of non-genetic influences on gene expression) utilised data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth to examine the intergenerational transmission of discrimination, concluding that hormonal changes initiated in response to the stresses of continuous exposure to racism play a significant role in ill health.[2] At around the same time, a number of health practitioners, writing in the Journal for Pain Research, examined the relationship between repeated exposure to racial discrimination, chronic stress and chronic pain. The authors concluded that ill health and early death can induce changes in gene expression without altering the underlying genetic sequence, and that can be shared across generations..

A comprehensive inquiry – but on whose terms?

The recent research evidence in the UK seems to have encouraged at least some in the leadership of the NHS to break ranks with New Right race thinking and analyse the statistical data on ethnicity anew. The NHS Confederation has commented: ‘The ONS data underscores the necessity of a more comprehensive review than the one currently being led by Public Health England. As part of this, we need to look into issues of structural discrimination that may compound equal access to care, as well as health inequalities that continue to persist.’

Keir Starmer has initiated Labour’s own inquiry, and Sadiq Khan for some unfathomable reason has called upon the Equalities and Human Rights Commission to investigate. The EHRC is the subject of increasing frustration, both for its flawed methodologies when investigating racism in higher education and its failure to address Islamophobia in the Conservative party.

The matter of Covid-19 infections and appalling death rates is a critical one for communities, deserving of the most serious and profound inquiry. But our experience to date is that often such inquiries become whitewashes, and/or recommendations end up sidelined and gathering dust in the archives of an organisation. Now is the time that grassroots voices must be heard. Any potential inquiry members need to be beyond reproach – that is, not part of those who routinely blame immigration and multiculturalism for complex and multi-faceted social problems. They have to be prevented from using pseudo-science or cultural arguments as a dog whistle to promote far-right politics. Equally, it is important that anyone who claims to represent BME communities is not tainted as any type of race science fellow traveller, and has a track record both of delivering practical support to BME communities and struggling for equality and social justice for all.

The right questions and the next steps

An inquiry so established and independent of state influence will be able to focus on the lived reality of Covid-19 to understand the disproportionate deaths in our BME communities. It would ask why, for example, BME women make up over half UK pregnancy hospitalisations with Covid-19. It would examine the number of cases, severity of cases, and treatment of those cases, to begin to try to understand how far our excess death rate comes from increased exposure, increased health risk, or inferior care.[3]

We can then ask that the inquiry examine the extent to which BME staff were pushed into frontline situations and were less likely to receive adequate PPE. To examine also the extent to which exposure through employment, living conditions (including higher housing density and overcrowding), lack of effective design and communication of public health advice, and inadequate testing and tracing, made it more difficult for our communities to isolate effectively and therefore contributed to higher replicability. How did increased exposure contribute to increased severity from higher viral load? How far did racism and epigenetics factor as additional stressors and how far did other environmental factors, including poor air quality, contribute to increased severity? How far was direct racism in response to Covid patients present in primary care interactions leading to sub-optimal advice, worse treatment by ambulance services leading to later hospitalisation, and worse treatment by hospitals leading to poorer treatment choices and increased deaths? Given that all factors are likely to have been intensified for those in our communities that are subject to immigration control (especially those with no recourse to public funds), how far did the nexus of migration status and rights to health (including charging regulations and data sharing), impact on our communities and undermine the adoption of the necessary whole society approach to maintaining ‘public health’?

We have seen the potential of a robust public health approach to drive change in the NHS and ensure compliance in the population. Whether we be community activists or health care professionals, NHS managers or trades unionists, we need to harness that capacity for change to ensure that investigation into Covid-19 disparities does not compromise with the race realists and explicitly addresses the role of racism in the course of the pandemic. If it does this, it will be likely to expose the extent to which racism today is the hidden public health crisis.

Wayne Farah is a black health activist with 20 years of experience as a non-executive director of NHS boards.

What an important and necessary article when the inquiry by National Health England led by Kevin Fenton seems not to be considering racism as the major factor to be analysed and the context within which this pandemic has developed.

Well researched article. Thank you, Wayne.

The Public Health England report into BAME Covid-19 deaths is now out.

It states what we already knew.

It fails completely to analyse or even suggest why there are more BAME deaths from Covid-19.

It fails to suggest any remedy.

Can we imagine any ‘Independent Public Inquiry’ into the government’s handling of Covid-19, or the preponderance of BAME deaths, being set up by the government?

A really independent public inquiry will need to be organised from the grass roots up – a People’s Public Inquiry.

Some of the groundwork has been done. In this excellent article and elsewhere

Let us invite those who have organised similar inquiries in the past, in the areas of health services, public health, social care, and equal rights to come together to launch this one.

Thank you for the article, very comprehensive and thorough in pinning down the causes and challenges of disparities. Especially the concerted effort by the New Right to deflect from a social to an unfounded biological basis to inequality.

Thank you Wayne. A very well rounded article and so much to learn from.