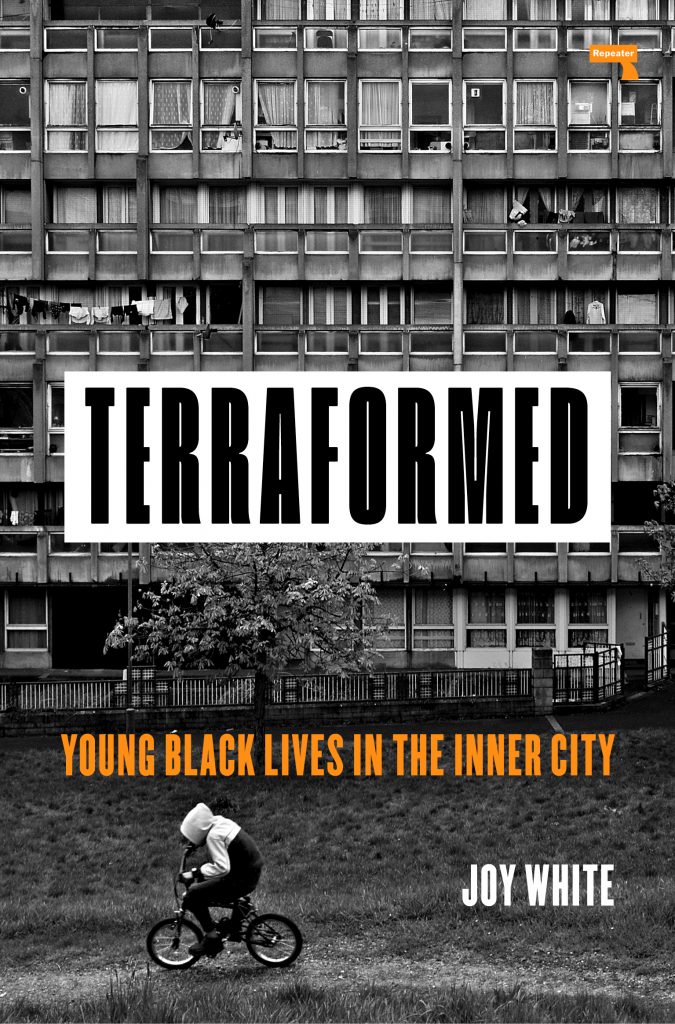

IRR’s Jessica Perera interviews academic Joy White about her 2020 ethnographic book Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City, which reads as a telling riposte to the recent Commission for Race and Ethnic Disparities (CRED) report.

Commentators have argued that the approach behind the CRED report brings to mind a league-table[1], where points are awarded (or not) depending on whether you are deemed as coming from a good or bad ethnic minority, reflecting the winner and loser ideology of neoliberalism. The ‘failing’ are exhorted to find routes out of their culture to success. But, as Joy White argues here, a deep nihilism has set in for young working-class Black communities in London’s inner city, and its effects are yet to be acknowledged.

Jessica Perera: Can you tell me the basics about ‘Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City’?

Joy White: Topographically and sociologically, east London has changed a lot over the past forty years, and I wanted to support young Black working-class people to make sense of the challenges they face owing to these changes. To be frank, I wanted to make sense of it for myself. My aim was to connect the dots for example between gentrification, austerity, youth violence, and describe how these processes have pressed down on Black youth.

At times, it was difficult for me to write Terraformed because I was overcome with a sense of grief and rage at what is happening to our community in Forest Gate, something I think a lot of young working-class people can relate to. I wanted to try and get across the continuity of struggle across the generations in Newham. What I mean is that many of the struggles that my generation faced with racism in housing and policing persist today, they just look different at times. It’s easy to see how some young people can end up with ahistorical views when there has been a deliberate attempt to not include Black histories in the school curriculum. You know, many young Black people have little sense of how they came to be here and do not know how my generation resisted state racism.

The young people in my working-class community want to make sense of their lives. One of the questions that kept on cropping up in my research was ‘why is it that no matter how much you do and how hard you try, we never get anywhere?’. Even the ones that were supposedly ‘doing the right things’ like getting a job or going to university, were still asking this same question. And that is because the neoliberalism is not just something that is happening out there, it is happening to us, and many young people have internalised it so that now it has become common sense to think that their lack of ‘success’ as an individual is their failure. I come from a time when ‘failures’, if we can call them that, were understood in relation to the state.

JP: Your exploration of the nihilism experienced by some young working-class communities is compelling. Why did you feel the need to address it?

JW: There is a deep collective feeling of weariness, confusion, hopelessness and disillusionment among some young Black and multicultural communities in the inner city. Many young people might not express their emotions using these words, but many feel like their lives do not matter and have no value. That might be distressing to think about, but we need to. The thing about not having hope or looking forward in a purposeful way tells us about the state of society, and it can also take away capacity to care for ourselves and others. That’s not to say that young people do not care about others, but capacity for caring can get lost in deep feelings of real futility.

The experiences of young people in Newham are not unique. It is the story of every multicultural working-class community in London. The type of ‘individualism’ that young people are demonised for has not appeared out of thin air. It is the result of social, economic and political changes that have made this particular group not only surplus to the labour market, and locked out of education and housing, but has engendered a winner and loser common sense, so that young people blame themselves when they are unable to get on in life.

JP: Thinking about nihilism from this psychosocial angle is important, but does it mask deeper political issues?

JW: It seems to me that where there are feelings of hopelessness there is hostility toward the government – whatever colour it is – and where there are feelings of confusion, there is also rage. Being lied to, unsurprisingly gives rise to anger and working-class youth have been lied to by the government. They were told if you get a university degree this opens the door to the world of work and a better life. Well, that is not exactly true, is it?

When life is difficult, complex and challenging it is sometimes easier to turn to a conspiracy theory to try and make sense and make use of that anger. But, at the same time, that is not to say that a politics of some sort is not emerging. The pandemic, if anything, has provided an opportunity to ask important questions about the conditions of their lives; they do not want to return to normal, because normal is not working for them.

JP: Do you think the nihilism we are talking about has been divorced from structural changes in society, and what effect do you think this has had on young peoples’ mental health?

JW: I talk about the walking wounded – young people who have not just been on the receiving end of trauma but have watched their friends experience trauma, and as a society we talk about ‘youth violence’, but we live in a very violent society, and that violence is mainly structural. It starts in schools and ends with the criminal justice system. The effect on young people is under-acknowledged and there is very little provision and support available to them.

JP: Of course we need better services for young people experiencing issues with their mental health, but is that in a way looking at the symptoms when we should start with investing in social infrastructure, like housing and education?

JW: Yes, services that treat mental health problems are, at times, only dealing with the symptoms, rather than dealing with the issues that allow those symptoms to emerge in the first place. In Terraformed I try to explain that the material things needed to make life worth living are out of reach for many.

I left school when I was 16 and left my mum’s home when I was 21, so by my early twenties, I was living a fully independent life. Until I was 30 I was working in administrative and clerical jobs, and while I earned very little money, I was still completely independent. Today, working-class youth are forced to live at home for longer or sometimes, forever. Or they face years of temporary and insecure accommodation that is often not fit for purpose. This holds people back and weighs them down.

It should go without saying that we invest in social infrastructure, but a lot of people are surprised that many poor people don’t live in places where they are always warm and you have access to appliances and equipment that work.

Ordinary people are really struggling. There is no safety net to help people when they fall on hard times, and that can happen to anybody. The answer has always been from the government that there is no money, well there is money, as we have discovered during the pandemic. The pandemic has shown us with the furlough scheme, for example, that when the government want to produce money, they can. We shouldn’t have to get to crisis point before money is made available. The government should be investing in young people, and for a time that was the rhetoric, you know ‘children are the future’ – well if they are the future, then look after them. Instead, the government now see young people as a nuisance, they need keeping in check, they don’t want to see them having any fun or enjoying themselves – you know they can’t be too loud or too visible. And for some young people from certain communities, they really have been rendered out of place.

JP: Would you say that young multiracial working-class people living in the inner city have been left behind, despite the government not acknowledging this in its official ‘left behind’ discourse?

JW: This ‘left behind’ discourse is a part of a much older colonial history. Communities, that are Black and Asian, have never been considered full citizens that deserve the same rights as white people. So why should we be surprised now that we are excluded from contemporary conversations?

JP: How can we understand the idea of ‘left behind’ in relation to Black music, particularly Grime?

JW: I think Ghetts said ‘I’m a mirror – come to my area for 24 hours and tell me what you see’. The music emanating from the inner city mirrors hardship, impoverishment and pain – feelings that indicate a sense of ‘left behind’.[2] But DIY contemporary Black music is also a way for young people to express themselves and find innovative ways to talk about what is happening around them, among other things. The beauty in the music is that it’s not all just about pain, there is joy in it too. Grime and other contemporary Black music allows musicians and listeners to psychologically move beyond the confines of your estate, neighbourhood or borough.

JP: In Terraformed you say: ‘you could hear the music, the laughter, the chatter and plethora of sounds that let you know that young Black adults are in existence but they are just not in the public arena’. Did you mean that walking around gentrified London, it seemed like working-class youth have been disappeared?

JW: During the research for the book, I came to realise that different kinds of people are visible on the street and others are not. For those that are generally not, that is because there are consequences when they are out and about in public spaces, on street corners, in parks, on the edges of estates. Young people can be moved on, and if they refuse to be moved on, then it doesn’t take much for them to come up against the criminal justice system. Receiving an ASBO, for example, is a quick route to that system, and so the only way to stop that from happening is to not ‘be about’. And that, we need to recognise, is quietly enforced by state authorities. Working-class Black youth are constantly surveilled; they are not able to move freely around the city, especially in groups. They must remain cautious and vigilant at all times, which surely affects their mental health. Is this really the kind of city we want to live in?

JP: The CRED report suggests that Britain is the diversity and inclusion model for the world and any disadvantage is due to poor parenting and personal failure. Doesn’t this line of argument heap more responsibility on individuals and excuses the state from needing to offer forms of security?

JW: I wrote ‘Terraformed’ partly because I did not want to continue with futile conversations on the existence of racism in Britain – structural or otherwise. I wanted to show how the concept of ‘meritocracy’ – the notion that anyone can make it if they just work hard enough is a mirage. Looking at societal issues mainly from an individualist perspective, whether it is framed as poor parenting, personal failure, or some other thing, offers little recognition of the systemic, structural and racial inequalities that have existed in the UK for a long time. We know that the hostile environment towards Black communities in the UK goes back decades. Anti-Black racism in the UK is underpinned by a collective amnesia with regards to the terror of Britain’s colonial and post-colonial endeavours. Superficial accounts such as the thoroughly discredited CRED report offer a kind of revisionist forgetting and simply another distraction.

I’ve really enjoyed this article and am intrigued to read Joy White’s book. I think it’s crucial that we pivot away from the “does racism exist? And if so, how much?” conversation to one that challenges the ideas (i.e. meritocracy) that the state supports and foists on those who fail within its system.