As the government announces that NHS England and Public Health England will lead an inquiry into the disproportionate impact of coronavirus on BAME communities, a Black health activist warns that the vague social construct of ‘race’ is being used to explain the mortality and morbidity of diverse populations, and more must be done to hold NHS England and Public Health England to account.

‘We are all in this together’, they declare. However, as the recently announced inquiry into the disproportionate impact of coronavirus on Britain’s Black communities illustrates, some of us are more in this than others.

This government must be held to account for its failure to protect us by not following the basic principles of emergency planning, public health, infectious disease control, or advice from the World Health Organisation (WHO). The leadership of the NHS must also be held accountable for their role in the unnecessary deaths of NHS patients and workers. They must not be allowed to shirk responsibility as they did over the deaths and forced destitution of staff and patients in the Windrush scandal.

Race – now you see it, now you don’t!

We are told Covid-19 does not discriminate – it doesn’t need to because the apparatus of the state (including the NHS) do. That the virus would strike hardest at the most vulnerable, was predictable and predicted. From the outset there were clear warnings that Covid-19 was ‘exposing the fault lines in society. Prince and pauper may be affected in the early stages, but as the pandemic proceeds, social distancing reveals inequalities. That’s what the data show’.

Initial concerns over the way the emergency response to the pandemic was being racialised began with comments on how BME workers were being airbrushed out of images of the NHS in the media. The criticisms grew as the deaths of front-line clinicians revealed the true face of the NHS. Figures show that whilst BME communities account for 14 percent of the UK population, they make up 44 percent of NHS doctors and 24 percent of nurses. But 70 percent of front-line workers who have died are BME, and they make up 34 percent of the critically ill patients – an over-representation that appears consistent with the data emerging from the USA, where African Americans are also vastly over-represented in Covid-19 cases and deaths.[1]

But did this racialisation change when Boris Johnson gave thanks to the immigrant nurses who saved his life, or when Matt Hancock shed crocodile tears for the dead Muslim immigrant doctors? This was surely different from Trump, who labelled Covid-19 ‘the Chinese virus’ for advantage in trade negotiations, or the response of the Italian far-right politician Matteo Salvini, who linked African asylum seekers to Covid-19 to bolster his call for border closures. Could this, along with the proposed inquiry, be a sign of a more inclusive political discourse?

The British state’s reactions to reports from Scarman to Moore-Bick via Macpherson and Cantle, demonstrate its long and successful track record in absolving itself from the consequences of the institutional racism it has created. Asking NHS England & NHS Improvement (NHSE/I) and Public Health England (PHE) to lead the inquiry is reminiscent of the old trick of police investigating themselves, such as when Kent police investigated the role of the Metropolitan police in the Stephen Lawrence case. The government is ignoring the obvious conflict of interest, and I suspect that, as the police always have, the NHSE/I and PHE will be filling their buckets with the whitewash needed to ensure their institutional racism is not exposed and scrutinised.

The Nightingale: frustrations grow

Doubts as to NHSE/I and PHE’s capacity to comprehend, let alone investigate, the role of racism in the pandemic, began with concerns about the new Nightingale hospital in Newham. Newham has the most diverse population in Europe – over 140 languages are spoken in Newham’s schools and over 70 percent of the population are BME. Newham also has some of the highest rates of child poverty and overcrowding in England along with very poor health outcomes and health inequalities.

This is where the new hospital has been built, bringing people from all over London who have the virus. They, by whom I mean the leadership of the NHS, saw no reason to explain to local people why bringing Covid-19 patients onto their doorstep did not create a serious risk to them. They professed incomprehension that the name ‘Nightingale’ was controversial, and refused to consider that ‘Seacole’ may be more appropriate. They managed to recruit an all white management team for the London hospital, despite BME staff comprising almost 50 percent of London NHS staff. They gave private sector contractors NHS badges so they had privileged access to local stores, leading to queues and shortages for local people. They had ambulances parked outside the empty hospital for PR purposes, whilst local people saw an increase in waiting times. If the fear, frustration, and resentment brewing in the local communities ignites, the NHS leadership will no doubt once again express complete incomprehension.

Emboldened by genetics, scientific racism resurfaces

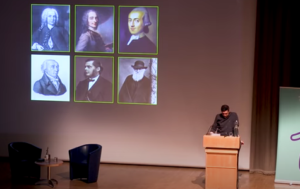

Rather than the inquiry providing a mechanism to hold the NHS national leadership to account, if we are not vigilant, it will merely serve as an opportunity for them to articulate and establish highly dubious norms around race and health. The current thinking around race and health, in my view, represents a reworking of the scientific racism born from Enlightenment thinkers’ efforts to biologise human variation. Linnaeus, Voltaire, Kant, Huxley and Darwin all contributed to establishing race typologies and racial classification schemes in accordance with the white supremacist ideology that justified colonial expansion, plunder, and exploitation. Once assumed to have been discredited by the Holocaust, these ideas seem to be resurfacing, albeit in new forms.

The prime minister’s racism of watermelon smiles, ‘piccaninnies’, and letterboxes is rooted in the hierarchical racial classification schemes that were the bedrock of scientific racism. They will be familiar to NHS leaders given the western medical establishment’s long history of scientific racism; from the abuse of Sara Baartman, J. Marion Sims’ experiments on enslaved women, the harvesting of Henrietta Lacks’ cervix cells, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and the Africanisation of the AIDS crisis.

Today’s modern take on the old scientific racism is emboldened by genetics, but degrades the science to espouse a biological essentialist, monogenetic, genetic deterministic, biological nationalism. It has been increasingly embraced by the New Right since Charles Murray advanced the idea of a ‘cognitive elite’ and sought to establish racial differences in intelligence. It is attractive to the New Right because it argues that as the racial classification has a genetic basis, it makes no sense to construct social mitigations for disadvantages that are biologically determined. Dominic Cummings is clearly attracted by genetic arguments,[2] and his advisor Andrew Sabisky frankly articulated the biological deterministic argument prior to his resignation.

What should really concern us is the ways in which some of our NHS leaders seem to borrow from genetic arguments in explaining the racial contours of the Covid-19 pandemic, even as they ignore criticisms from within the BME communities about the structural causes of racial disparities.

NHS leaders argue that the high BME death rate can be explained by the greater risks arising from comorbidities, and over-representation in lower socioeconomic groups. The comorbidities proposition essentially suggests that the vague social construct of race is an adequate explanation for mortality and morbidity in diverse populations. They present research data that shows high rates of diabetes among South Asian people and hypertension among African-Caribbean populations, suggesting such comorbidities explain the high BME death rates.

Best practice in race and health research

Many forms of social stratification are important in health research, and stratification by race is assumed to be useful as a proxy for genetic similarity. However, the evidence showing that race correlates with genetic variation is weak. Given that there is greater variation across populations living within Africa than there is between all the other populations of the globe, this is unsurprising.[3] There is some evidence linking genetic variations with frequency distributions of specific diseases, eg, sickle cell disease. However, most of the data suggesting a correlation between certain socially constructed ‘racial categories’ and disease prevalence is highly contested because it is plagued by definition drift, slippage, and ambiguity. It does not validate the social construct of race, which arises from processes of racialisation, informed by social values and institutional practices and hierarchical thinking. It imbues superficial differences between groups, such as skin colour, with unwarranted significance in order to recast social inequalities as biological realities. Research using racial categories tends to over-emphasise the role of genetics as the basis for health disparity and deflect from the socio-economic and political determinants of inequality. It supports ‘racialisation’ and promotes the belief in the genetic underpinning of social inequalities, and thus influences how findings of difference are interpreted and translated into clinical care and health policy.

The NHS is using ‘racialised data’ to argue that Black people are dying from Covid-19 because they are sick. They assume that the correlation between diabetes and South Asian (socially and vaguely defined) populations, is both real and somehow causal. Correlation is not causation, but for NHS leaders it seems the question is answered. Asians get diabetes because they are Asians, Blacks have hypertension because they are Black, and there is no intervening variable, such as racism or epigenetics[4] that need concern them. Therefore ‘it’s nothing to do with us folks’ – just the inevitable outcome of biological inheritance and melanin distribution.[5]

Structural factors and work environment risks ignored

In addition, NHS leaders suggest that those who aren’t dying of comorbidities, are likely dying because they are from lower socioeconomic groups living in high-density, resource-poor settings, with an accompanying higher risk of viral spread. Put simply, those of us who are not dying because we are Black, are dying because we are poor, even though there is no data yet to confirm a similar spike in deaths of poor white people with diabetes or hypertension etc.

Of the three million people in high-exposure jobs in the UK, the essential workers who are not allowed to self-isolate, even if they could afford to, are mostly women – many earning ‘poverty wages’ for precarious work on part-time, temporary or zero-hour contracts. In many sectors, including health and social care, BME and migrant women are hugely over-represented, meaning that low-paid, BME and migrant women currently putting their lives on the line to deliver vital care, were previously told they are low-skilled and therefore undeserving of settled immigration status, liveable wages or stable contracts. It is the poverty and insecurity that inevitably flows from structural and instructional racism that has made them vulnerable, but for the new scientific racist and New Right, they are just living their genetic inheritance.

But what about the doctors?

However, the poverty that NHS leaders claim accounts for the racial profile of the victims in the general population cannot explain the profile among doctors. They are not poor, lacking access, resources or knowledge. Their risk factor is their work environment. Many of our leaders appear deaf to the overwhelming cries from NHS staff about invisible or inadequate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Yet the data from their own Workforce Race Equality Standard and staff surveys point to long-established institutionally racist practices as critical risk factors in BME staff deaths. BME staff are more likely to be harassed by managers and subjected to disciplinary procedures by their Trusts, Royal Colleges and regulators, and are therefore less likely to speak out. How far such fears prevented BME clinicians challenging managers over PPE, or any disproportionate allocation to Covid-19 wards, must be given full consideration.

Similarly they appear to have ignored the decades of data confirming BME communities’ lack of equitable access, worse health outcomes and higher levels of dissatisfaction with the NHS. If they had not ignored this, they would have anticipated that institutional racism would intensify in times of crisis. They would have sought to mitigate the risk of racialisation in the allocation of scarce life and death resources at the outset.

The leadership of the NHS often declares its total commitment to equality, diversity, and inclusion. If policy papers and speeches were sufficient, the NHS would be free of all forms of racial discrimination, but it is not. Therefore we need to collate, verify and harness the clear evidence from our communities, and utilise our experience fighting state racism, to ensure the ‘snowy white peaks’ of the NHS do not use the inquiry to whitewash the NHS. We must also prevent them from legitimising the arguments of the far Right by exposing how structural and state racism enabled the selfish genes of the Covid-19 virus to lay waste to the poor, marginalised, and demonised Black and migrant communities, and expose the role that institutional racism in the NHS has played in that process.

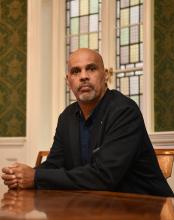

Wayne Farah has 20 years of experience as a non-executive director of NHS boards

Brilliant article. On this ample evidence of racism by the white NHS team must be exposed and punished those guilty of these crimes.

Excellent, insightful, clear and sharp analysis. Joins up so many dots and exposes previously hidden links and connections. Definitely worth reading! Thank you.

One of the best articles I have ever read. Period. More please. More importantly more distribution to the public and professionals alike. Thank you.

Excellent and well researched article, my friend Wayne.

Dr Satheesh Mathew

So well written

Thank you.

Is there a network of BAME NEDS and chairs nationally, if not, there should be

So well written,

Is there a network of BAME, NEDS and chairs, if not should there be one

Thanks

Any investigation needs to come from speaking directly with our communities, and overseen by our own community leaders and members.

The article is very good. We as BME need to fix this ourselves with better education and training for BME so that they do not find themselves in this position. As much as we have rights over government resources, it is also our duty to educate and improve the lives of the BME population and healthcare workers.

Excellent article, well documented and clearly written. Let’s make sure justice is done!

Well researched article which should not only stimulate discussion but more importantly action.

A well written article. This warrants further Investigation. Hope justice will be served. More opportunities for BAME to unite and let their voices be heard.

just to add to the discussion that the chronic stress of experiencing discrimination itself leads to poor health outcomes (which can explain higher vulnerability to covid) even when adjusting for socio-economic factors

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eCeAzhKobk8

https://developingchild.harvard.edu/thinking-about-racial-disparities-in-covid-19-impacts-through-a-science-informed-early-childhood-lens/

So pleased I took the time to read this article. Very well written!

I work for the NHS and have been speaking out for yrs about the blatant racism that I and others have encountered on our daily duty at work. No one seems to Care or in the least interested in what we have to say. Deaf and Mute is the response.

It’s flogging a dead horse so to speak.

I will continue to pray for justice and a positive outcome one day.

Hope it’s a reality in my lifetime.

I had a first-hand experience of this. The management put us on the sides when it comes to encouraging us to progress in our careers. We are not offered any option. My example will say for itself. 5 yrs in Neurosurgery, not once ever offered to do Neuro course, whilst white newly graduate are offered all courses in the planet. I was incharge of the ward but not even shown how to head hold in spinal turns.

A colleague on mine, Indian applied for a band 6 but did not get the job, Reasons given was lack of experience, this lady was a bed manager and bleep holder at night for 5 yrs but she was told she does not have enough experience but the 1 who got the post was a white British nurse 2 yr post graduate. It shows without people talking about it that racism and discrimination is well culturally rooted.