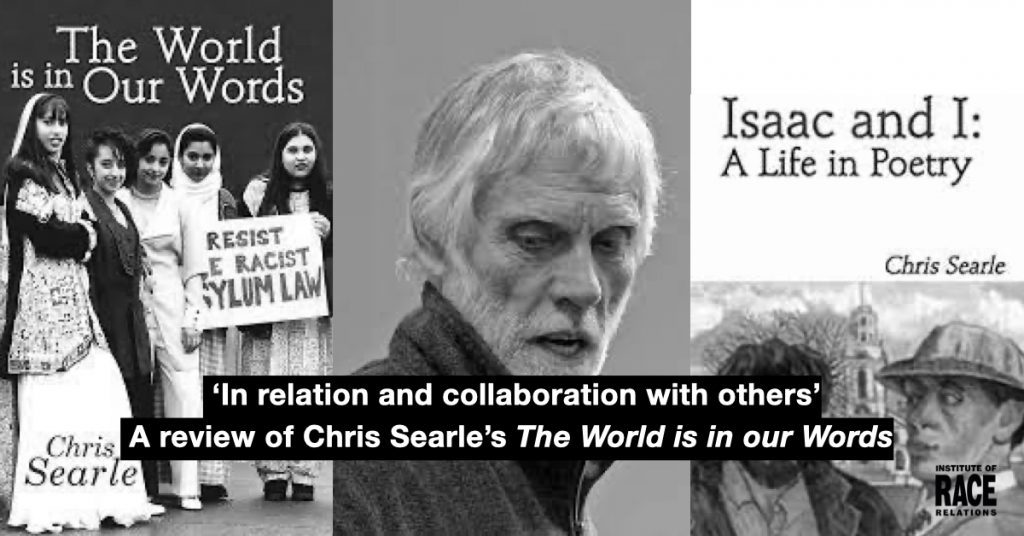

Teacher and poet Sam Berkson reviews Chris Searle’s The World is in our Words (Nottingham: Five Leaves Publications, 2022), an autobiography that incorporates the words and visions of many, whilst telling the story of Searle’s teaching, writing and anti-racist mobilisations as a schoolteacher in Sheffield, where he established one of the first non-exclusion policies.

In 1997, Chris Searle interviewed the Nigerian novelist, Chinua Achebe. Achebe told him, ‘The story is more important than the writer, although they are related … It is the story that conveys all our gains, all our failures and all we hold dear and all we condemn.’ The World is in Our Words is the second part of Searle’s story of his life, and it is the story more than the writer which is emphasised. Hence, the choice of cover photo – not of himself but a group of his Sheffield students protesting the 1994 Asylum Bill.

Fortunately for the reader, Searle has lived an extraordinary life and met some extraordinary people, both ‘celebrities’ like Achebe or otherwise, like the young women from Sheffield on the cover. The book takes up his life in 1979, after his return from teaching in revolutionary Mozambique. He skips over his time in revolutionary Grenada (he has written about this elsewhere). However, the lessons he learned from those two ‘Revos’ are embedded throughout.

A memoir that dwells on all the celebrities the writer has known and met is generally a tedious read. However, name-dropping or basking in reflected glory is not Searle’s way. Instead it is more of a jazz album of a book, incorporating many voices to convey the ‘gains’ and ‘failures’ of a life that was always lived in relation and collaboration with others, for collective purposes not individual achievement.

Jazz of course is one of Searle’s loves, and another of the frames he uses to understand the world. As a poet and teacher myself, of a younger generation, I was involved in the UK Hip Hop Education network, using a different black musical form to understand and develop our pedagogy. ‘Teacher ear is as important as pupil voice’ was one of the lines of our collectively written manifesto and I am sure Searle would approve. The memoir records and presents many of his pupils’ poems and creative writing. It is the voice and opinions of young and old learners (he also taught adult classes, including retired Yemeni-born Sheffield steel workers) from multicultural, working-class communities that seems to maintain Searle’s faith in life.

Faith in life for left-wing internationalists has been hard to maintain in the decades of neoliberalism which the book covers. Nevertheless, Searle’s optimistic view of humanity is rarely derailed. He is content to consider himself lucky to have lived the life he has, and to share the insights and creativity of others, rather than use the book as an introspective evaluation of his own achievements or emotional development.

One moment where we do hear more of the ‘writer’ than the ‘story’ is when Searle tells us how the collapse of the Grenadian revolution ‘filled me with incomprehensibility and despair’. It is no surprise to read that he ‘had never felt that way before’. His response is to ‘move on’ and throw himself into yet more work, ‘if anything’, feeling, ‘more dedicated to a socialist view of the world’. When living is hard, find more story, you might say.

The despair takes him to Sheffield and his efforts to create a practical anti-racism in the Local Education Authority, firstly as advisor for Multicultural Education and then as headteacher of Earl Mashall school in Fir Vale.

His time running a ‘non-excluding school’ shows why the Left needs to keep reading about our ‘failures’. Searle recounts the development and the tragic ending, the project derailed by a combination of reactionary teachers and a teachers’ union; negative stories in the media; a Panorama documentary; and some powerful opponents, including one of the then Sheffield MPs, David Blunkett.

In the spirit of incorporating first-hand voices not just re-telling events with hindsight, Searle quotes himself from the time, defending his school in the Sheffield Telegraph. Their approach to ‘challenging’ children was to ‘keep them within school as much as we can and to work with them to change their behaviour.’ Reading it now, when abolition has become a framework for a number of young activists, it feels important to remember Searle’s attempt to abolish exclusion at Earl Marshall. Meanwhile, while many educationalists are arguing against exclusion just as Searle did 30 years ago, those who advocate the opposite have their voice continually amplified. Tom Bennet, the DfE’s behaviour adviser, for instance, continues to argue that exclusions are ‘absolutely necessary to preserve the safety and learning of students’, happy to ignore the learning and safety of the students he wishes excluded.

In the end, an OFSTED inspection put Earl Marshall ‘under special measures’. Following Blunkett’s secret letter recommending Searle’s dismissal, Searle was indeed dismissed. A failure, perhaps. It reminds us that if we ever seize the organs or infrastructure of the State – whether that be secondary schools or the Labour Party – the media and powerful forces will turn against us. However, the ‘gains’ of our approaches in the limited time we have to try them and in the hostile social conditions in which we attempt them, should remind us that things can be – and have been – done differently.

Searle ends the book with poetic exchanges. Poems written by First Nation Canadian young people in response to poems of young people from Sheffield. Poems written by children in Manchester for Nelson Mandela’s 90th birthday. Poems written in Stepney in 2016 in response to poems written there in 1971. It is a whirlwind of a life-history, telling the story of a life lived with incredible energy and continual optimism, incorporating the words and visions of so many others, not just his own. Searle’s faith in internationalism, anti-racism and socialism, is maintained, as for many of us teachers, from his time spent working with young people. He reflects, ‘I have marvelled at the ability of young people not only to reach out and empathise with others in faraway places of the world but through their ever-incisive imagination to emulate each other’s forms and modes of poetic expression within the universality of childhood’. It is that universality that enlightens us among the particulars of an extraordinary story.