IRR’s Jessica Perera continues her examination of the human cost of estate regeneration by talking about pride and potential with a north-west London poet.

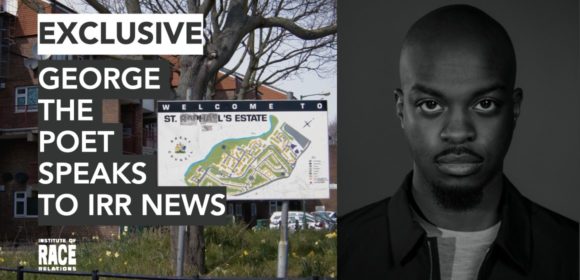

George Mpanga is a London-born spoken-word poet and host of the award-winning ‘Have you heard George’s Podcast?’ If you have not yet discovered the podcast, you might be more familiar with its accompanying advertising posters: ‘it’s hard to listen when you’ve never been heard’ that are dotted across the capital. Concerned that his community on the housing estate he grew up on, St Raphael’s in the north-west London borough of Brent, would not be heard during the current regeneration consultation, George recorded a poem explaining the fears the community had regarding the redevelopment plans.

George Mpanga is a London-born spoken-word poet and host of the award-winning ‘Have you heard George’s Podcast?’ If you have not yet discovered the podcast, you might be more familiar with its accompanying advertising posters: ‘it’s hard to listen when you’ve never been heard’ that are dotted across the capital. Concerned that his community on the housing estate he grew up on, St Raphael’s in the north-west London borough of Brent, would not be heard during the current regeneration consultation, George recorded a poem explaining the fears the community had regarding the redevelopment plans.

The interview took place before the coronavirus pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests, both of which George has commented on elsewhere. However, with recent policing of ‘block parties’ on estates in multicultural areas of London during the coronavirus lockdown, the interview has taken on a new meaning as we witness the type of community connection that George talks about. Though some parties may have broken social distancing rules, so too have Liverpool football fans and sun-seekers flocking to beaches in their millions. The difference is the former comprise a section of society that is stigmatised and subjected to violent policing, beatings, arrests and fines according to their race, class and locale. While the latter, at the very most, get a slap on the wrist. While estates teem with excited youth, happy to be reunited with their family and friends, many of whom they live close to but have been unable to see, their wrists remain exposed to cuffs.

Jessica Perera: Can you tell me about what’s happening with regards to the regeneration of St Raphael’s estate, where you grew up?

George the Poet: Brent council decided in November 2018 that St Raph’s required regenerating for a few reasons. One is that there is a lot of overcrowding and apparently the estate, as it currently stands, does not maximise the land available for residential accommodation. But, another reason is that a redesigned estate could, it has been suggested, better deter ‘social challenges’ like ‘gang’ activity and crime. The argument is that an estate with better facilities would help St Raph’s residents who struggle with unemployment and low educational attainment.

JP: In a nutshell, Brent council want to ‘design out’ the ‘social challenges’ faced by the community at St Raphael’s?

George: Some people on the estate are opposed to the idea of regeneration. There’s a lot of suspicion. We haven’t always had the greatest relationship with the council; we are largely from ethnic minority communities and have often felt powerless when it comes to engaging with the state. Some are curious about the plans, however, and are interested in what opportunities regeneration might bring. But ultimately the community want to be consulted by the council and architects. But we’re figuring it out, there is a mixture of tenures; the majority of residents are council tenants, but there’s a minority of homeowners.

JP: Brent has the second highest rate of housing overcrowding in London. This is a huge issue for families and also the council, which needs to build a lot more housing to support working-class people. We hear shocking stories from communities across the capital who are often promised the social housing they need through regeneration, but later find out they will be displaced. Do you think St Raph’s could turn into another exclusionary regeneration project?

George: There is always the possibility of exclusion when the people most affected by these decisions are not sufficiently engaged in the decision-making process. At the moment, while Brent council has assured us that it will seek maximum engagement and no one will, apparently, be moved on from their homes. I want greater reassurance that my community will be informed at every turn, that is why I wrote the poem.

JP: Sixty-five per cent of Brent’s population is black, Asian and minority ethnic and for one in five residents in the borough English is not the first language according to an official report. How do language barriers affect the flow of information from council to community?

George: It is a very real problem that bugs me. Some of the residents have been asking their children to translate during meetings, but when they are not around it makes full comprehension very difficult. This breeds insecurity and distrust in people.

JP: What I loved about your poem George is your pride as you express your affection for the estate. For many who have never grown up on an estate, they can be seen as scary places, especially with all the negative media coverage. But we know they are really the only places left that any semblance of community exists. In the poem you say: ‘everywhere I go people wanna know why I’m like this, I tell them straight, I’m from St Raphael’s estate, and I say that with chest’. What does St Raph’s mean to you?

George: I went to a grammar school as a child, and I was very conscious at the time that I came from a council estate and the middle-class kids were obsessed with that fact. As I got older, I learned about outside stigma attached to council estate life, and at the same time, about the real problems facing my demographic, among a dispossessed and disillusioned group of young men in particular. It overshadowed my teen experience. Now that I am older, I am able to see my upbringing at St Raph’s gave me blessings that others may not recognise. I want to empower other people like me, who have a stigma attached to the area they’re from, to embrace the good in their neighbourhood.

JP: You also describe St Raph’s as your ‘thinking and breathing space’ and that you ‘could never really leave this place’. Those are profound words that resonate with me – my estate and area are imbued within me. And that is why I feel the regeneration of our estates and of our multicultural working-class communities is devastating. For people not from ‘the block’ it might be hard for them to understand estates are more than just concrete; they are spaces and places where ‘community’ is lived, where communal social reproduction flourishes.

George: Yes, I notice that more and more. Looking back on my youth, the way that we interacted and grew together as a community, it is not commonplace. To have residential areas that also have communal playing spaces, and where kids go to the same schools and make their own cultures parallel to the mainstream – that’s very special. And when you think about forms of music that emerged from these contexts, they have filled us with potential, enriched us and given many of us careers. Grime and other genres emerged off the block and have provided a platform for the inner-city experience. This wasn’t a government initiative and it wasn’t state supported, but because of the community that we had growing up we were able to generate a lot of opportunities from it and it has saved lives.

JP: In Sian Berry’s report into youth centre cuts in London, I noticed that Brent council had cut its funding between 2012/13 and 2018/19 by 15 per cent (Berry states that no new financial data has been provided by Brent council since). What effect do you think a decade of austerity has had on young people?

George: Life is hard for young people, but it’s hard for them to know what they’re missing. There’s been no example of fully functioning services in their lifetime. When I was younger there were so many play-schemes on weekends, in half-term and during the school holidays all run in local spaces like schools, sports centres and youth clubs. As an example, I used to attend a big project called the Brent Summer School, which kept me very busy, broadened my social group, and equipped me with new skills – it was a very positive experience that young people now are unable to access. But these experiences helped me to develop my interests – creative, technical or otherwise. And that was big man. Summers would have been very different without those services. Now that these council provisions have been removed, communities have to find new creative ways to keep our young people sufficiently engaged. But there is another problem, there are, generally, no designated spaces for young people to explore, learn and build. Working-class children and young people’s youth are not being protected, nurtured or honoured, and because of this they are being forced to grow up quickly. Because our parents are at work a lot of the time, our young people cannot be supervised inside or outside all day either. But we cannot rely on the government to help us, their budgetary trends indicate they will not find practical solutions to help us; we will have to change things for ourselves.

As frustrating as the situation is, with the removal of our protected spaces and the mischaracterisation of our youth in the media, we need to step-up in the absence of state support and ensure that the incoming generation of working-class youth are supported by us, by new social businesses that we create. In some respects, we need to let go of the idea that government has a sophisticated understanding or sufficient interest in working-class life and the challenges we face. We’re going to have to use our expertise on the ground, in our communities, even if we’re still developing our own skills and CVs. We must continue to create community on our own terms. Now, I’m not saying we should give up political campaigning altogether, but we must practice mutual aid in the meantime. We need all bases covered.

JP: A lot of my work focuses on how the 2011 rebellions, perceived by the political class as ‘crisis’, allowed the state to reshape the narrative on estate regeneration. The depiction of estates as ‘ghettos’, where ‘gangs’ operate, allows the state to win consent for renewal. In terms of Brent, home to many housing estates, has the depiction of particular areas as crime-ridden been used by councils and the state to initiate redevelopment plans? I noticed in your poem that Brent councillor Eleanor Southward explicitly states in the video that regenerating St Raph’s provides an opportunity to ‘design out crime’.

George: The government’s reaction to the ‘riots’ was absent of any economic analysis, because it is widely imagined as, and this phrase really irritates me, ‘senseless violence’. And similarly, every time a young person is murdered on the streets – which is obviously a tragedy that I’m sure so many young people would reverse if they could – the phrase ‘senseless violence’ is thrown around.

The idea, that crime and community trauma perpetuated by young people is ‘senseless’, is insidious, because it feeds into the idea that there is no logic to these people’s problems. But the logic is profoundly economic. When I was younger, I was offended and felt bitter about some of the things I had witnessed and gone through on the estate; I didn’t know how to understand it – we have a lot of frustrated, abandoned young people. In order to understand the true complexity of these issues we need to move past clickbait headlines and ask commentators to really scrutinise what is happening in people’s lives.

Those that talk about ‘designing out crime’, ‘gang activity’, ‘senseless violence’ and ‘knife crime’ neglect context, in fact, it would seem they are not interested in context. But what it allows is this continued demonisation of a group in society that are excluded from these conversations. When you look at the prison population and specifically young offenders, in 2006 I think there were 2,831 young offenders in this country, by 2019 there were 894 – so that population has decreased by about two thirds. But why is it then, that the proportion of white young offenders has fallen by about 70 per cent, whereas in the same period the proportion of black young offenders has doubled at a time where there’s been a significant reduction. The media has a lot to answer for, why is it not interrogating these issues and conducting proper analysis? A lot of the issues that are most relevant to me and my community, the government and media ignore, unless it’s attached to a racy headline about us. We have young people killing each other on the streets and being imprisoned at an alarming rate, and the government’s response is Chicken Shop box campaign, that tells you a lot.

Can you add a link for the poem? Love to read it, I used to spend all summer at the Lancaster West Play Centre at the base of Grenfell tower, happy memories of silk screen printing, enamelling candle making and mystery trips. My first theatre experience was with the centre too. I believe it shut down in 1985 never replaced in the same way.

Hi Juliette. The link is embedded in the word poem in the article but you can also find it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T23-zW9Jz38