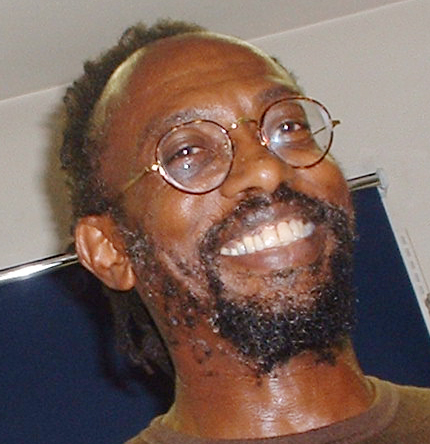

Colin Prescod, the long-term Chair of the Institute of Race Relations, explains, in a speech to the Historical Materialism Conference, 2013, how, as a Black activist, academic, and film-maker, he gravitated to the IRR.

We thought that it might be useful to this reflective forum if I spoke about ‘how and when’ I came to the IRR and to Race & Class. This is meant to be more than mere anecdote. It is intended to give a bit of colouring-in to one corner of the large landscape sketched in Sivanandan’s earlier interview remarks to this conference – a way to demonstrate how the challenges to ‘orthodoxies’, that Siva referred to, came out of the need to comprehend as well as to assist in combating the very direct oppression and injustice faced by late twentieth-century Black, working-class migrant settlers in the UK.

These new worker-citizens of the 1970s were not taking racial attacks and institutionalised injustice lying down. They resisted vigorously, in any way that they knew how. And it was out of my involvement at that time with these 1970s communities of resistance that I came to the door of the IRR.

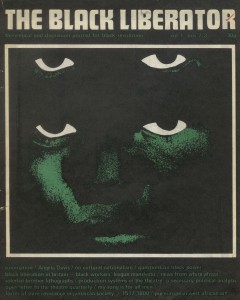

It could be said that back then I made the journey from a journal called The Black Liberator (TBL) with its collective, to a journal called Race & Class and its collective based at the IRR. The founding-editor of The Black Liberator (A X Cambridge) had been schooled in the Communist Party of Great Britain – but he’d stepped away from the party to convene a group of activists, Black and White, committed to delivering a theoretical and discussion journal for Black liberation. TBL sought to address, support and join the variety of resistances to racism that characterised what were then termed community struggles, as well as to situate them nationally and internationally.

Black politics of the time

To give you a flavour of those times: these were the times of the outrageous ‘Sus laws’, implemented by police and judiciary, and used to persecute, intimidate and drive young Black males in particular off the streets. In effect they were all under suspicion of either having committed or being about to commit a crime. These were also the times of the obscene characterisation of Black Caribbean children in the state educational system as ‘educationally sub-normal’ – where numbers of Black children in a number of schools were segregated as not capable of being educated alongside the rest.

To give you a flavour of those times: these were the times of the outrageous ‘Sus laws’, implemented by police and judiciary, and used to persecute, intimidate and drive young Black males in particular off the streets. In effect they were all under suspicion of either having committed or being about to commit a crime. These were also the times of the obscene characterisation of Black Caribbean children in the state educational system as ‘educationally sub-normal’ – where numbers of Black children in a number of schools were segregated as not capable of being educated alongside the rest.

Community protest at these kinds of crude discriminations was militant and loud and insistent, and resistance was imaginative. These were the times of energetically inventive community self-help – campaigning parents’ organisations; myriad supplementary school set-ups; make-shift as well as formally registered housing associations; the first neighbourhood law centres. These were the times of march after march in Black neighbourhoods; week in week out demonstrations at police stations, and inside and outside of law courts – and so, these were the times of increasingly violent community confrontations with the police as agents of the state.

We had then our UK version of militant Black Power – when for the first time guns entered the field of militant Black struggle – startling in a culture nothing like as familiar with everyday personal ownership and use of guns as that of the USA, say. That singular event was the Spaghetti House Siege of 1975, I think. There, three young Black men, two of them associated with organised militant Black struggle, attempted to ‘liberate’ the takings of an Italian restaurant in central London, just around the corner from the rich people’s store, Harrods. For at least two of the young men, the intention was to obtain money to fund ‘the struggle’. This was historic! They were novices though. And, to underline Sivanandan’s insistence on grounded-research commitment of the Institute – I recall that there was a hastily pulled together group/committee which attempted to mediate on behalf of the young militants, at the point at which their action had been turned into a siege by the Metropolitan police, over several days. That mediating ‘committee’ met and deliberated in the basement of the IRR’s rundown building in King’s Cross.

Black as a political colour

It was in these times that Black was forged as a ‘political colour’ in the UK – the colour of a politics of resistance, as distinct from merely a non-White skin tone term of abuse. This Black was one with a common anti-colonial and Third World heritage. It was anti-racist and therefore anti-imperialist. It included Africans (continental and diasporan), as well as, Asians (Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi). (Note, by now the laughable notion of ‘the passive Asian’ had been turned around, as Asian communities also resisted immigration humiliations, and, unfair discrimination, as well as, a variety of life threatening racist attacks on their communities.)

This kind of Black community was new too. It turned back the once successful colonial divide and rule ideologies – in the face of a common racist ‘foe’.

Out of these militant traditions eventually came a variety of what were termed ‘local riots’, which began to bite in the late 1970s, and which peaked as ‘urban uprisings’ by the early 1980s. In these uprisings, elements of the militant Black working class had ‘infected’, and been joined by, elements of the militant White working class. And, interestingly, the media and academics did not and could not characterise these as ‘race riots’.

I started by saying that in the mid-1970s I came to the IRR and to Race & Class from TBL. Thereafter I swiftly gravitated to the IRR and its journal – in part, because TBL could not sustain itself – and that, in part, because TBL needed to and never did confront, as Race & Class did, the need to make the language and analysis that it used intelligible to the people it was struggling for and very much alongside. People loyally bought the journal at campaign meetings, on protest marches, outside tube stations, at the major food street markets – but, few of them could read and comprehend much of TBL analysis. For me the high point of absurdity for TBL came in the late 1970s, when one issue of the journal featured a ‘glossary of its glossary’ – so highly theoretical and rhetorically hide-bound was its editorial policy. I became fully committed to the IRR and to Race & Class.

Documenting the struggles

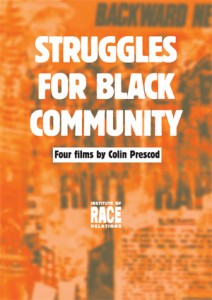

To close these brief remarks, I should reference the IRR’s engagement with documentary film – in particular the making of Struggles for Black Community in 1982, a four-part series of films commissioned and broadcast by the then brand new and still tolerably liberal Channel Four TV. The films were directed by me, and researched and produced by Race & Class Ltd. You can sense, I’m sure, the smiles on our faces as we operated under that moniker.

To close these brief remarks, I should reference the IRR’s engagement with documentary film – in particular the making of Struggles for Black Community in 1982, a four-part series of films commissioned and broadcast by the then brand new and still tolerably liberal Channel Four TV. The films were directed by me, and researched and produced by Race & Class Ltd. You can sense, I’m sure, the smiles on our faces as we operated under that moniker.

These Struggles… films, valued historical archive today, were and could only have been made on the basis of the IRR’s grounded research and analysis, and the trust that resisting communities across the country had in our integrity. The archival authority of these films today rests on our simple filmmaking dictum at the time, which was to give voice to people in struggle, and to broadcast their messages as unmediated by outsider commentary as possible. We took testimony only from hands-on community activists. We edited their voices to create seamless narrative analysis. And there is no editorial commentator’s voice in the films.

Our history with documentary film really started with Blacks Britannica, 1978 – which I made with director David Koff (later of Occupied Palestine fame). That film was commissioned by WGBH, USA. And what a furore followed! The film uncovered evidence of militant Black working-class responses to the reality of oppressive and exploitative capitalism in Britain – calling a spade a spade. When given a limited screening at the then vital Other Cinema, in London, sections of the rightwing press in Britain, with active support from one or two Conservative party politicians, denounced it and mounted a concerted attack on its credentials. I recall that, without any sense of irony, I was dismissed as ‘an armchair academic’ with no idea of what was actually going on with ordinary Black people. But all that was as small beer compared to the action of WGBH when they received the film that they had commissioned. They immediately made a wholesale re-edit of our film with some cuts, which they broadcast without our permission. David Koff and I publicly exposed their bad faith. They claimed that in their opinion our cut of the film would not have been understood by the US audiences. Progressive copyright lawyers in the USA took up our case against WGBH, for free, and we were in court for a year or so – until, in 1981, WGBH suddenly dropped their defence, surrendered copyright to David Koff and agreed to destroy their screwed-up re-edit of our film. What had changed was that in 1981 the world witnessed global news broadcasts of simultaneous riotous uprisings in tens of UK cities and towns – of the sort that had been predicted, in 1978, in Blacks Britannica.

Finally here, I should say that during this last month I have been completing the editing of not a film but a 35-minute filmed document, essentially un-cut – and we propose to title it Catching history on the wing – a filmed conversation with Sivanandan. It will join the body of reference materials available from the IRR.

Related links

Read the interview with A. Sivanandan here

Listen to the interview with A. Sivanandan here

Slide show on the IRR’s history

Download a copy of a selected bibliography on Sivanandan and the IRR here (word doc, 76kb)