A new project Fighting Sus! brings the youth experience of racialised policing to the fore.

In Fighting Sus! a group of young people engage with past struggles against racist state violence and, with angry intelligence and politicised creativity, range themselves against its present manifestations. Developed during 2018, this grassroots history project began with a handful of Year 10 students in East London – all from BAME backgrounds– collaborating with oral historian Rosa Kurowska and heritage cooperative On the Record. Their focus on the fight against the ‘sus’ law in the period 1970-81 became an exercise in reparative history, ‘excavating histories of resistance, solidarity and collectivity as vital for the now’.

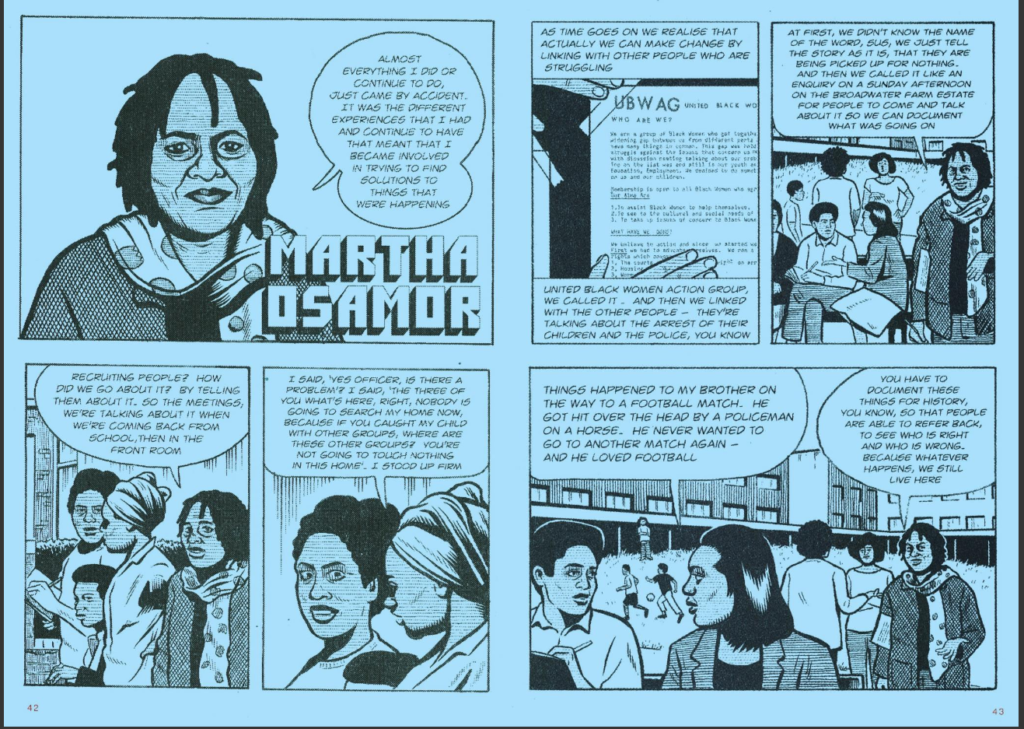

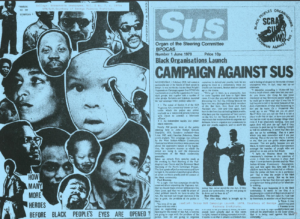

Fighting Sus! is a considerable and timely achievement. The content available for review, accessible online, includes: interviews with community activists who participated in the struggle against sus; a zine, which places the interviews– pictorialised into comic strips by Jon Sack– beside the team’s spoken-word responses to them, along with reproductions of documents and images from the archive; learning resources for an anti-racist curriculum; and a video featuring performances of the poems.

After Macpherson

Institutional racism persists two decades on from the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Report. It still determines who is harassed by the police ‘on suspicion’ and who is not. Racially disproportionate stop and search rates began rising again in 2003 and remain high. What Sivanandan said after Macpherson is as true now: ‘the performance on the ground for the black community is racism as usual’. Notwithstanding, the regime of racial neoliberalism has worked to downplay institutional racism even as the targeting and policing of racialised groups has intensified.

The substitute, more comfortable notion of ‘unconscious bias’ serves to blank out state racism and, from a historical perspective, disconnects us from past struggles against it. But counter-histories are, and always have been, transmitted along more grounded channels, often in overt contention with official narratives. This is ‘true history’, as understood by Saqif Chowdhury of Fighting Sus!: ‘A history taught us by our mothers, our/fathers, our ancestors/ The truth, the experiences of those around us’. This is ‘the history they want us to forget’, and which Fighting Sus! reactivates.

The project is important because BAME youth, though often talked about—as victims or as problems—rarely gain entry to the public sphere as opinionated subjects, despite possessing the clarity born of experience. Even as critical a review of the Criminal Justice System as the 2017 Lammy Review suffers, as Liz Fekete argued, from ‘an absence of the youth voice, or an acknowledgement of their perspectives in their own words’. Fighting Sus! brings the youth voice to the fore.

Scrap sus

Scrap sus

What was sus? Section 4 of the 1824 Vagrancy Act gave police officers the discretionary power to arrest anyone they suspected of loitering with intent to commit an arrestable offence. A survival from a much earlier period of social upheaval, following the mass demobilisation of soldiers after the Napoleonic Wars, it was redeployed intensively from the sixties onward against young black men in Britain. They could be arrested, charged and convicted simply for walking down the street.

As the IRR argued in its submission to the Royal Commission on Criminal Procedure in 1979, a sus charge was ‘virtually impossible to rebut’—the subjective word of two police officers sufficed. In the first interview in Fighting Sus!, Hackney activist and poet Hugh Boatswain reflects on his first experience of it: ‘the problem with sus for us was that it was your word versus whoever arrested you’—and it was enough simply to be black and ‘in the wrong place at the wrong time’.

Sus was acutely felt in a post-Powell climate of escalating popular racism, ranging from everyday intimidation to ruthless murder. The relationship between the street and the state was clarified during events like the Battle of Lewisham in August 1977. The National Front chose to march through Lewisham because it was a key sight of organised resistance to racist policing, exemplified by the Lewisham 21 campaign. During the march, police protected National Front members but confronted the mixed anti-fascist crowd with cavalry and riot shields (for the first time on mainland Britain). A striking photo from the day is reproduced in the zine.

The racial disproportionality of sus arrests in London was well-documented by the late 1970s (see the Runnymede Trust’s 1978 publication, Sus – A Report on the Vagrancy Act 1824). It was a key mechanism in the racialisation of urban space, maintaining the whiteness of certain areas and policing the blackness of others. And it was the latter that became the ‘symbolic’ locations, as 1982-87 Met Police commissioner Kenneth Newman described them, of community self-organisation against police brutality.

A movement to ‘scrap sus’ developed through the politicisation of everyday experiences of police antagonism. Images and documents from two campaigning groups appear in the zine. In her Fighting Sus! interview, veteran black activist Martha Osamor recalls how black mothers discussed the issue during the school pick-up. They would go on to campaign against it as the Black Parents Movement. The Black People’s Organisations Campaign Against Sus (BPOCAS), a broad coalition of black groups and lawyers, launched later, in 1978. Effective campaigning by BPOCAS and others forced the issue onto the government’s agenda, and by 1980 the Select Committee on Home Affairs would recommend immediate repeal, which was achieved in 1981.

The anti-police uprisings of that year, beginning in Brixton on 10 April, gave repeal an added urgency. But this was reform not transformation. In his state-commissioned inquiry into the Brixton uprising, Lord Scarman conceded that the mass sus operation that triggered it, Operation Swamp 81, was ‘unwise’. But he rebuffed the broader accusation that the Met police was institutionally racist. Only a few bad apples tarnished the force’s reputation, he concluded. In ‘Scarman’s Speech’, Jolina Bradley’s poem in Fighting Sus!, a different Scarman is imagined, heralding a more hopeful future. He says: ‘I respect, acknowledge, invite and envision what could be’. But the question remains whether substantive change could ever have come at the instigation of the state.

‘Where does it start? Where does it stop?’

‘Where does it start? Where does it stop?’

The myth of policing by consent became even less tenable after 1981. Accordingly, Fighting Sus! looks beyond the moment of repeal. Campaigns against police violence continued—the Fighting Sus! team interviewed Goga Khan, one of the Newham 8 defendants tried in 1983, and the zine contains an image of a Newham 7 demonstration in 1985. England would burn again in that year. As Osamor remarks at the end of her interview: ‘they repealed [sus]. But if you look at the law as it is now, it’s stop and search… It’s still happening’.

The 1981 Criminal Attempts Act, which repealed sus, was succeeded in 1984 by the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE), which in effect reinstated it as stop and search. The proviso of ‘reasonable suspicion’ was ineffectual. Stop and search was expanded later in Section 60 of the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which introduced targeted emergency powers. In 1999, Macpherson recommended a series of regulatory mechanisms but did not fundamentally question the practice itself. A year later, Section 44 of the Terrorism Act legitimated racially profiled stop and searches. And although it was ruled illegal on human rights grounds in 2010, Section 60 continues to be rolled out.

The zine’s introduction wisely suggests that ‘sus may have embedded itself into modern society’, and Liza Akhmetova asks in her poem: “where does it start?/ where does it stop?’ This is Fighting Sus!’s key historical insight: that the policing of suspect communities in Britain is a prevailing logic of social control under racial capitalism, manifest in laws and practices that change over time. The project acknowledges this with the scope of its timeline, which stretches from the original 1824 legislation—and its introduction to the colonies after the formal abolition of slavery—all the way through to the Riots and the Windrush Scandal of our decade. Regimes of race have changed throughout, but always as part of a connected and unfolding racial-colonial history.

Creative, collective resistance

More than the sum of its products, for those involved Fighting Sus! was a year-long process. Initially, research and discussion, in dialogue with the interviewees. Then the creative responses—in music, spoken word and other forms—which were performed in nine venues across London during Black History Month. There was also the production of the 45-minute film, the zine, and the teaching materials for schools. Practical workshops were held along the way, for example, on stop and search rights with Adam Elliott-Cooper. Altogether, this would have been an educative, creative and collective experience.

The forging of solidarity through the project is clear in the all-women group performances of ‘Mangrove 9’ (01:17) and ‘Verbatim’ (34:05) in the film. However, most of the poems still contain distinct individual perspectives. Brandon Leon and Jessica Lima understand sus as a ‘prison out of prison’, part of a web of control. Memuna Rashid’s poem ‘The System’ begins similarly but turns towards struggle and the freedom dreams that sustain it. And a harder vision of the future can be found in Rotimi Skyers’ poem, which invokes the flames of past uprisings, but scaled-up to a revolutionary vision of the end of the world as we know it: ‘and if the whole world burns, for us to come in from the cold,/ then let the whole world burn’.

The fire this time

The fire this time

Fighting Sus! gathers a previous generation’s history and a new generation’s hope, despair and rage in one place. Thanks to the team, an archive dedicated to sus, the first of its kind, now exists at the Bishopsgate Institute. The project invites other young people to explore this and related histories for themselves, to create their own archives and develop responses to them. The zine’s back matter lists key archives for further research—including the IRR’s own Black History Collection—and includes the details of some organisations—Y-Stop, Stopwatch and Release—where information, advice and political involvement can be sought. More projects like this need to be funded and realised.

Visit the Fighting Sus! website or order a copy of the publication by emailing On the Record.