It’s time to kick-start a debate on abolitionism and immigration enforcement, argues Liz Fekete.

Abolitionist perspectives, though perhaps understated, have always been central to refugee and migrant struggles against racist immigration controls in the UK and Europe. And with nativist governments hardening themselves against any immigration reform, as the backtracking over the Vulnerable Children’s Resettlement Scheme, demonstrates, they are now more needed than ever before. Since 2018, abolitionist solutions have been put forward by grassroots migrants and refugee groups from across Europe at various sessions organised by the Permanent People’s Tribunal on Asylum and Migrant Rights. And, at a recent ‘Solidarity knows no borders’ rally organised by Migrants Organise, which has initiated the Fair Immigration Reform Charter, speaker after speaker also spoke to an abolitionist agenda. In what follows, I draw on the lived experience and powerful testimony of migrants and refugees, to consider how to further build abolitionist perspectives within our movements.

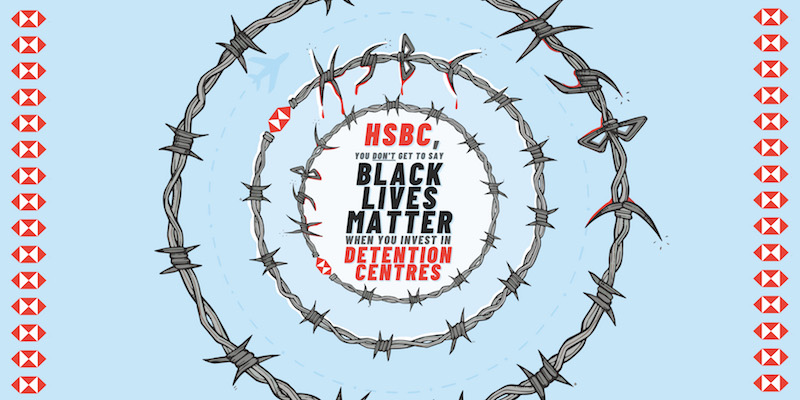

The centrality of defund/divest

First of all what does abolitionism mean, and how do the arguments relate to immigration policing? BLM abolitionist Adam Elliott-Cooper, responding to Labour party leader Sir Keir Starmer’s belittling of the demand to defund/divest from policing, argues that abolitionism does not mean shutting down every prison and sacking every police officer tomorrow. But it does mean reducing police powers and resources, in recognition that endless expansion of police and prison systems has not contributed to public safety.

In the migration context, immigration policing is the fastest growing and least accountable form of policing across Europe. In the UK, the Home Office and other agencies engaged in immigration enforcement are amassing ever more resources and powers, with the estimated net resource cost for Home Office immigration enforcement being £392 million in 2019-20. Meanwhile, Frontex (the EU’s border control agency) has gone from a budget of €6m in 2005 to €460m in 2020. The fact that budgets are expanding exponentially relies on a habitual recourse to the portrayal of migrants and refugees as a ‘threat to our way of life’. Abolitionism entails rejecting that threat-based scenario and resetting the way we view immigration – so it is not seen through the lens of law and order, but new frames which foreground issues of justice, rights and fairness in the labour market.

Abolitionism involves imagining a society where things are organised differently – where education, rehabilitation, integration, healing, become the responses to the social crisis engendered by austerity and the erosion of the social safety net (cuts in spending on health, education and affordable housing). The punitive response to social problems, includes the criminalisation of migration, [i] the creation of temporary camps where the displaced are concentrated in the most appalling conditions, and the global construction of detention centres, run for profit by private companies where people are warehoused prior to removal. As Showing Up for Racial Justice in the US reminds us, ‘Punishment and control have become the State’s automatic response to its failure to meet basic needs’.

Once we have realised that mass criminalisation (of migrants and citizens alike) is taking us over an authoritarian precipice, we can start to identify the government policies that need to be abolished if we are to win back ground for justice and rights. Having made a leap in imagination, we can set about applying our vision to today’s realities and start thinking about how to enact the ‘non-reformist reform’ – ie the reform that shrinks the law-and-order state rather than expands it.

Central to the abolitionist case, as articulated by the Movement for Black Lives in the US, is the demand to ‘defund the police’ and invest in social services (divest/invest). It is a demand that recognises, in the words of Barbara Ransby, that ‘we can’t just patch up the system that we live under’ and we can’t just abolish, we have to build, as ‘to abolish without building leaves us vulnerable’. Far from this being pie in the sky, abolitionism not only starts from a sound analysis of the profound harms that the law and order approach to social problems has caused, but it is also very practical. It argues that we should take money away from the police and redirect it downstream – so that we deal with mental health issues, fund youth clubs, take torture victims to a place of safety where they can receive therapeutic care, etc. From an immigration perspective, one would naturally have to question the role of a law and order ministry (Home Office) as the lead government department on immigration policy. One simple demand would be to take unaccompanied minors to a place of safety rather than leave them enduring the daily harassment and physical violence of the immigration police and far-right vigilantes, and exposed to early death attempting to leave the makeshift camps in places like Calais.

Abolish wrongs, establish rights

The principle upon which we could build our abolitionist demands is very simple: ‘abolish wrongs, and establish rights’. A draft manifesto prepared by the London Steering Group of the PPT Tribunal on asylum rights (that focussed on the hostile environment in the UK) calls for ‘a rights-based approach to immigration policy which empowers migrant and refugee people and provides the political and social space where they can assert their interests against those of the state’. In this sense, abolitionism in the immigration sphere could be seen as an attempt to reverse the xeno-racist logic of nativist governments that have been busy abolishing the rights of those deemed ‘foreign’. (In the UK, this even extended to the Windrush Caribbean generation, here since the 1950s, and, under hostile environment logic, classified as ‘non-citizens’.)

Moving forward from this principle, our first step would be to call for an end to laws that, in criminalising those who cross borders ‘illegally’, drive them into the arms of traffickers, [ii] leading to tragedies such as the Dover 58 and the Essex 39. We would demand that humanitarian principles are put to the fore when judging asylum claims, including an end to the ‘culture of disbelief’ within immigration systems. The militarisation of borders would also have to end. We could use the billions we save by divesting from militarised borders, to pursue policies that save lives. That is what the captains and crews of search and rescue (SAR) ships like the Iuventa have been doing in the Mediterranean Sea – and yet they have fallen foul of laws that criminalise solidarity. [iii] We may not, at the moment, have the power to totally abolish the militarised sea and land border, but we can take other steps to defy its logic, and build on the work of SAR NGOs.

Of course, all of this is piecemeal, unless we also target the institutions that maintain global capital and call on them to cancel debt and disinvest from policies that harm the global South institutions such as the IMF. The World Bank should stop imposing public spending and public services cuts in Africa, for instance, and European states should stop tying development aid to the enforcement of European immigration controls. An abolitionist position in terms of immigration policing is by necessity an anti-war position. We would centre the displacement of people caused by neoliberal resource wars, including bombing oil-producing countries in the name of the war on terror. This, as seen in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Libya, is, along with environmental destruction, the main cause of forced migration.

Building through education

If prison abolitionism encourages us to reimagine prisons as sites of education – transforming the prison into a school – immigration abolitionism encourages us to envision ways we can support young unaccompanied refugees through investing in their education. We could demand the abolition of laws that deny unaccompanied minors the right to a university education, once they reach the age of 18. [iv] We could also build a wider strategy around education, foregrounding teacher training and the curriculum – so that all teachers and student are equipped with the true facts about the reasons for migration and refugee flight, and understand the harm that arises from stigmatisation, dehumanisation and racism. If we encourage children from an early age to be intellectually curious about the world they live in, if we teach them about the true nature of the global crisis of forced migration, if they are well-versed in the international dimensions of the UK labour market with its global supply chains, if they learn about the structural needs of our agricultural, service and care economies, where migrant workers pick the crops, put food on our table, care for our elderly – then they will grow into better-informed adults. Far from being emotionally invested in the scaremongering and hate of the media and the far Right, they will stand up to racism. In this way we would actually reduce crime – ie, crimes of racism and fascism, including threatening behaviour, incitement, assault, arson (of asylum hostels) and racially motivated murder.

Abolishing fake crimes

Once we start here, it should be obvious that laws that criminalise refugee movement, [v] and make it impossible for migrant workers to access services, [vi] or place unfair, discriminatory and class-based obstacles on the accession of residence rights, [vii] would have to be abolished. It’s not just a question of defunding the police, it’s also a question of dismantling laws that, in creating a huge number of new criminal offences, have led to so many people imprisoned, at great cost, for administrative offences against immigration laws.[viii] It would no longer be a crime to be without papers, and people would no longer need to fear imprisonment, or the immigration raid to catch ‘illegal’ workers, as a rational system of work and residence permits would be applied. In a fairer and more rational system – one in which forced migration is addressed downstream – we would not need immigration detention centres, as not only would we be investing in real sustainable development, but we would no longer consider it civilised to warehouse and concentrate people in detention centres for the crime of irregular status. Disinvesting in the punitive global approach means no more warehousing, no more concentration camps like Moria or Kara Tepe in Lesvos. Disinvestment in the ‘camp’ would mean taking people to a place of safety, rather than abandoning them in conditions, as in Lesvos, where they are exposed to environmental hazards and denied basic rights to housing, adequate food and water, sanitation etc.

Tackling the crime of exploitation

The coronavirus pandemic has shone a light on the centrality of migrant labour in European economies. Imagining a society free from the super-exploitation of migrant workers necessitates a rethink of state policies that both facilitate exploitation and then let unscrupulous employers off the hook. The money we could gain from disinvestment in immigration policing and disinvestment from militarised borders could be used to tackle the criminal tendencies of employers who believe that the super-exploitation of the vulnerable migrant is their inviolable right. It would involve taking money away from immigration policing and putting it into health and safety inspections and the enforcement of the minimum wage – an approach that would benefit all workers. We would argue for laws that incentivise employers to comply with legal obligations as well as protect domestic workers, cleaners, cooks, chauffeurs, nannies and personal carers in private households. We would dismantle all laws that place migrant workers in a situation of precarity – and in some cases modern slavery – and cause so much harm to their physical and mental health. We should call for an end to the use of fear (of detection, debt, and ill health) to ensure compliance of vulnerable people, as part of an abolitionist policy.

Abolishing the ‘No Recourse to Public Funds rules’, [ix] the condition attached to migrants’ permission to stay, that prevents them from claiming welfare benefits, has to be central to our abolitionist demands. During the emergency lockdown that accompanied the first wave of the pandemic in the UK, the Treasury-funded furlough scheme, as well as the social security system, excluded an estimated 1.4 million people from emergency support because of immigration conditions stipulating ‘no recourse to public funds’.

Abolitionism involves a fundamental rethink of the way we understand crime – the crimes of the powerful and the crimes of the vulnerable and the super-exploited – so that an employer who withholds wages or food so as to force compliance, is seen as the real culprit.

Hostile environment – state crime, ‘violence by design’

The hostile environment refers to the regime created to limit migrant access to public services, the use of aggressive immigration policing, the conscription of employers, landlords, university staff and medics into surveillance and enforcement and the establishment of nativist principles in employment laws. The jury of the London hearing of the PPT called the hostile environment a form of ‘violence by design’.

At the end of the day, the hostile environment, as we have seen with the treatment of the Windrush generation, is a crime in itself, a state crime, perpetrated every day by civil servants, immigration police and held in place by data sharing agreements [x] that make immigration officers out of employers, doctors, nurses, social workers and teachers. Hostile environment policies, as the PPT has found, are not an accident, they are a trap, generating precarity, exploitation and destitution, for hundreds of thousands of people seeking eventual settlement, who must endure years of struggle against types of employment which, although essential to the economy and society, are generally low-paid and often abusive in terms of workplace practices.

Putting investment in public services first

The NHS charging regime [xi] and data sharing agreements between the NHS and the Home Office stop migrants accessing medical treatment – a cruel system that has been shown up for what it is during the pandemic. If money was to be taken away from militarised borders and internal controls (often digitised), it could be given to the NHS which would once again return to its original principles of universal health care for all irrespective of immigration status. Such money could also be used to strengthen support for migrant women experiencing domestic violence, so that no woman is turned away, due to her citizenship status, from a refuge because she is deemed a foreigner and somehow less worthy of a place of safety.

Central to abolitionism is the call to dismantle state structures that build their legitimacy on an enhanced sense of threat. Systems that classify people, whether it be migrants or Muslims, black people or Roma, as a public order or national security threat, create harmful logics of ‘us’ and ‘them’ leading to punitive policing that endanger – rather than protect – lives. A law-and-order approach foregrounds exclusion and punishment; a defund and divest approach puts public safety and public health first.

An abolitionist perspective would also abolish the link between immigration policing and racial profiling. If we had fair immigration policies, the state would not need to embed immigration police officers in police stations [xii] or give them the power to ‘stop and scan’ [xiii] on our streets. As Luke de Noronha in his seminal study of deportations to Jamaica has shown, saturation policing (through stop and search, for instance) makes some people – particularly Black Caribbean – especially vulnerable to deportation. Not only does the heavy policing of young black people in the UK have deportation consequences, but racist policing and deportation are ‘mutually constitutive rather than sequential’.

As I have said, abolitionist demands have always been part of our movements. Campaigns around the injustices done to the Windrush generation, and others such as ‘Docs not Cops’, ’Patients not Passports’, ‘Against Borders for Children’, End Immigration Detention and Waling Waling, have chalked up considerable successes not through calling for reform of the immigration laws that established the hostile environment, but for their abolition.

Thanks to Frances Webber for her legal expertise and for fine-tuning the footnotes and to Don Flynn for his insightful comments on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

[i] The Immigration Act 1971, s 24, makes it a criminal offence to enter the UK without leave or to remain beyond the expiry date of a visa.

[ii] Immigration Act 1971, ibid. Article 31 of the Refugee Convention forbids the criminalisation of unauthorised entry of asylum seekers, but many asylum seekers and trafficking victims are detained.

[iii] The EU Facilitation Directive requires member states to criminalise assistance for unlawful entry to a member state. It allows, but does not require, exemption for humanitarian action, and many member states including the UK criminalise all assistance, whether for-profit or humanitarian. In the UK, the Immigration Act 1971 s 25 makes it a criminal offence to assist unlawful entry.

[iv] Unaccompanied minor asylum seekers who do not qualify for refugee status or humanitarian leave are normally granted leave until they are 17½ , and must then leave the UK unless they can qualify to remain in some other capacity: Immigration rules, para 352ZC. If they stay, they are undocumented and so ineligible for further or higher education.

[v] Refugees are unable to obtain visas (unless they are among the very few brought in under a resettlement scheme from a third country eg the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme, for Jordan or Lebanon), and so are forced to travel without visas or with false papers.

[vi] The Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016 require landlords to perform checks on the immigration status of prospective tenants and other residents before renting property to them, and barred undocumented migrants from driving or holding bank accounts. Access to welfare benefits has been linked to immigration status since 1993, and non-EU migrants excluded from benefits since 2000; and employers have been prohibited from employing migrants without authorisation since 1996. Undocumented migrants have in theory been ineligible for free NHS non-emergency hospital care for decades, but the NHS Charging Regulations 2015 and 2017 required NHS hospital staff to check immigration status and to charge patients ineligible for free care, at 150 per cent of the cost of treatment, in advance.

[vii] These include English-language and minimum skill and salary requirements for entry for work and for settlement, the absence of any route to settlement for those deemed ‘low-skill’, including domestic and care workers and NHS support staff; huge fees for entry and settlement permits and for citizenship: see Immigration Act 1971 ss3, 4; Immigration Rules, general requirements for leave to remain; Immigration and Nationality (Fees) Regulations.

[viii] There are dozens of such offences, in the 1971 Immigration Act and in many subsequent Acts including notably the 1999 Immigration and Asylum Act. The Immigration Act 2016 Act created the offence of illegal working.

[ix] Immigration rules, passim. Para 6 of the rules defines ‘public funds’. See also Home Office guidance ‘Public Funds’.

[x] Memorandum of Understanding between Department for Education and Home Office, 2015, which allowed the Home Office to access details of children and their families for immigration control purposes; Memorandum of Understanding between NHS Digital and Home Office on data sharing, 2017, allowing the Home Office to access patient details for the purpose of immigration enforcement.

[xi] The 2014 Immigration Act introduced the ‘immigration health surcharge’, then set at £200 per year, now £624, payable by all migrants who do not have settled status in the UK. See also note 6 above.

[xii] Under Operation Nexus, introduced in 2012.

[xiii] Border Force officials do not have the power to stop without reasonable suspicion, but they have powers of examination, arrest and search of those suspected to be in the UK illegally, under the 1971 Act and the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2000.

How true! well thought out and presented, Liz. Next steps?

Excellent panoramic overview of the potential that the abolitionist perspective holds out for campaigns to advance the rights of migrants. But in showing the possibility that this approach has for generating links to so many abolitionist projects it raises the question of over-arching priorities – which is to say where the migrants rights movement should be concentrating its resources to bring about change at this moment in time.

Some of the answer to that questions stems from the problem which lies at the heart of the government project as casting immigration as criminal activity per se. We shouldn’t under-estimate the resistance to this idea on the part of the the mass of people who hold the conventional view that crime is an activity that causes harm to other people, who can readily be identified as its victims. Governments want to argue that arriving at a border without having the required papers and visas to hand is on its own sufficient to render the individual criminal, but for most people who do not hold hard-line nativist views their is resistance to this idea. The months of pandemic lockdowns together with the looming threat of labour shortages caused by Brexit has revealed something of the world of the migrant worker to millions of people, and they have shown disquiet with regard to the idea that they have to be kept under exceptional surveillance and made to pay thousands of pounds in tribute for the privilege of staying ‘legal’. How can thew abolitionist perspective deepen this understanding and turn it into committed opposition to the immigration control regime?

Working for this deeper understanding means sharpening the critique of the state institutions which are specifically responsible for immigration control. Liberal reformist approaches on this score seem to hold out the idea that things like the hostile environment and the Windrush scandal are an aberration to the functioning of immigration control procedures which could be corrected by having ministers in charge who would be more ‘compassionate’. If an abolitionist perspective is to be applied here it would counter this with the insistence that the arm of the state given responsibility for managing migration is, in terms of its structural function and actual historical record, rooted as a matter of necessity in a ‘law-and-order’, criminalising approach to all aspects of immigration control.

Campaigns against detention, excessive surveillance, workplace immigration raids and other fronts where the state makes criminals out of migrants already exist and do excellent work. What is not said often enough, and the thing that still fails to come out as a sharp demand thrown in the face of politicians, is the call to end the role of the Home Office as the state agency responsible for managing migration. And this is despite the fact that the scandals of recent years have made the cruelty and futility of its law-and-order stance a patent failure by any standards.

I would say that the call to end the Home Office’s role as the department responsible for managing migration ought to be presented as a transitional demand which points the way beyond the current approach taken by the capitalist countries of the Global North. It poses the question, ‘Well, if migrants don’t figure as challenges to public order in our society, then what are they?” Campaigners for the human rights of migrants will be ready to give a detailed answer to that question.