Liz Fekete examines the role and importance of grassroots monitoring groups today in Europe.

This article was originally written as a contribution to a publication in which anti-racists across Europe marked the tenth anniversary of ReachOut, an anti-racist monitoring group in Berlin.

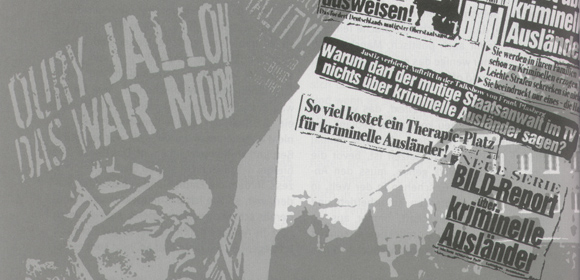

Why do we need independent groups to monitor racist attacks?[1] On the tenth anniversary of the Berlin anti-racist monitoring group ReachOut, and as the grotesque facts about the German police and intelligence services’ failure to prevent the murders of at least eight people by the National Socialist Underground (NSU) slowly emerge, the answer stares us in the face. States, which systematically downplay the extent of far-right violence, do not have a good record when it comes to protecting Black and Minority Ethnic communities from racist attack. Independent monitoring groups that create pressure from below are the only guarantors that police and criminal justice systems will be accountable to all the communities they supposedly serve, and that democracy and security are not the sole preserves of the majority.

The history of independent anti-racist monitoring groups

After the second world war, when Europe was desperate for labour, workers, be they Turkish, Moroccan, Algerian and other Gasterbeiter for Germany, France, Belgium and Switzerland, or Indian, Pakistani and West Indians from the UK’s former colonies, were invited to Europe, to work mainly in the manufacturing, construction, agricultural and service sectors. But despite their labour being vital to post-war reconstruction, nations did little to encourage settlement or foster integration. Discrimination in the market place was rampant and, in their daily lives, immigrants were vulnerable to the prejudice and violence of anti-immigrant and far-right movements. In the UK, which did not practise a guest-worker system, new immigrants from the former colonies had citizenship rights. Because they did not live in the shadow of a foreigners law, with its ultimate punishment of deportation, Britain’s Black communities were better able to exercise their civil rights, to defend themselves from racist attack and to campaign against police racism. It is not surprising, then, that the roots of Europe’s burgeoning, independent anti-racist monitoring movement today can be found in the UK where in the 1970s and 1980s grassroots activists established a whole network of community-based monitoring groups, inspired by the civil rights movements of the US. The ‘70s and ‘80s was a time for militant self-defence. The new community monitoring networks were established out of need and because of the absence of state protection; they represented the political voice of a black community which was adamant that it was ‘Here to Stay, Here to Fight’.

The UK model was certainly one that German anti-racist groups looked to when first forming counselling services for the victims of far-right violence. By 2000, when Alberto Adriano, a migrant worker from Mozambique, was murdered in Dessau and a bomb attack left ten people, mostly Jews, injured in Düsseldorf, they had become an established feature of German life. Up until then, the state had only funded groups concerned with rehabilitating offenders, but for the first time, state funding was to be provided to small, local initiatives against right-wing extremism, including the funding of support and counselling services for the victims of neo-Nazi hate crimes.[2] That ReachOut sets a professional and moral standard for other German anti-racist monitoring groups was evidenced in 2010 when, alongside other organisations such as AKuBiZ, it refused to accept the federal state’s new funding criteria under which it would have had to accept state definitions of terrorism and swear allegiance to the German constitution. The implication was that independence and integrity were of more value than state funding, implied – a fundamental principle of all bona fide community-based monitoring and anti-racist projects.

Independent research and defining of the struggle on their own terms (free from state or party political influence) was also a factor in the formation by Norway’s migrant communities of the Anti Racist Center in Oslo in the late 1970s. The need for independent monitoring is now acknowledged in Norway and groups like the Organisation Against Public Discrimination have ensured that neither the 2001 murder of 15-year-old Benjamin Hermansen by neo-Nazis nor the 2006 death in police custody of Eugene Ejike Obiora, went unchallenged. But what we have witnessed in Europe since 2000 has been unprecedented. Over the last decade, there has been a veritable flowering of grassroots, independent, anti-racist monitoring groups and movements – born, once again, out of intense need. For militarism, nationalism, patriotism, and the chauvinistic and hateful ideologies they engender are leaving deep scars across the whole continent of Europe.

The state of play

Today we are witnessing the resurgence of old hatreds, with the Roma, particularly in Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia, again scapegoated for the economic crisis. But attacks on Roma encampments and the Traveller way of life are now commonplace across western as well as eastern Europe. Another stain on Europe’s conscience is the constant barrage of attacks on ‘visible Islam’ – the promotion of enemy images of Muslims against the backcloth of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. And every day, attacks takes place on mosques, cemeteries, Muslims, particularly women who wear the veil. Marwa al Sherbini, murdered by a neo-Nazi sympathiser in a Dresden courtroom should be foremost in our minds.

Many of the newly-established grassroots organisations, across southern, eastern and parts of western Europe, work along the same lines and ethos as ReachOut. And this is often with little or no public recognition and, in many countries, with no state funding. There is, for instance, SOS Mitmensch and ZARA in Vienna (the only independent counselling group of its kind in Austria), the Never Again Association in Poland and In Iustitia in the Czech Republic. There is KISA in Cyprus, amazingly, its Executive Director, Doros Polycarpou, currently faces prosecution charges of ‘rioting and organising an illegal assembly’. (The prosecution reveals the state’s bias as the charges arose from an incident in which ultra-nationalists were allowed to attack a multicultural music festival in Larnaca in 2010.) In Spain, there is SOS Racisme, the Movement Against Intolerance and the Asociaciòn Proderechos Humanos de Andalucia, the EveryOne Group in Italy and the Immigrant Council of Ireland. It is attempting to deal with the widespread verbal and physical attacks on immigrants and black Africans in particular. In 2010 16-year-old Nigerian student, Toyosi Shittabey was murdered in Dublin. And the Migrants Network for Equality and the Movement Graffiti in Malta have highlighted the case of the Sudanese migrant Suleiman Ismail Abubaker, who died after being punched in the head by a bouncer outside a nightclub in Paceville in 2009.

The work of two pressure groups in Europe today stands out. The Collective Against Islamophobia in France has been steadfast in its opposition to the growing tide of officially-endorsed Islamophobia. Though ignored by its own Republican government, the CCIF which now has official observer status at the United Nations, tirelessly documents anti-Muslim incidents, while providing counselling sessions and legal advice for the victims of Islamophobia.

People Against Racism in Slovakia ran on a voluntary basis since the late 1970s but, in 2000, it was formally established as an NGO. It launched an action on behalf of the family of a Roma man, who died after being tear-gassed by police, in Tornal’a in May 2010. The Bulgarian People Against Racism was launched in 2010 in response to an attack by masked men, armed with metal rods, on four young asylum rights activists on a tram in Sofia.

If it were not for such groups, the larger NGOs such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, European Roma Rights Centre, the European Network Against Racism, quasi-international bodies like the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, and EU-funded agencies like the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, would be unable to produce their authoritative reports and research. Such pan-European and international bodies are also reliant on the daily reportage and research of anti-racist newspapers and websites including ICARE News and the IRR’s own independent anti-racist race and refugee news service.

New monitoring concerns

But now we find that the essential work of all these groups is under threat, not just from irresponsible politicians whose dangerous anti-multicultural rhetoric is leading to the downgrading of issues of racism, but also from a revitalised neo-Nazi and far-right terrorist underground. For the European-wide assault by centre-right parties on what Angela Merkel refers to as the ‘multi-kulti’ society has strengthened the resolve of far-right organisations which believe that immigrants are a ‘fifth column’ and that the multicultural society is a ‘social abscess’. Variously calling themselves the Free Youth, the Kameradschaften, the pro-identity, resistance or autonomous nationalist movements, these networks support the fascist thesis that the ‘creation of a multicultural society’ has led to ‘the systematic eradication of cultural identity’, indeed of ‘entire peoples’ and that multiculturalism represents ‘one of the greatest crimes ever perpetrated against humanity’. Declaring themselves at war with the doctrines of ‘tolerance’ and ‘liberalism’ and describing the ‘multi-ethnic society’ as ticking ‘like a time-bomb about to explode’, these violent networks of conspirators believe, just like Anders Breiving Brevik in Oslo and Gianluca Casseri in Florence, that those who support immigrants or Roma or Muslims are national traitors. And it is we, in the anti-racist movement, ridiculed by the state as supporters of cultural relativism, who find ourselves demonised as unpatriotic, our names collected and our activities spied on by groups such as the National Socialist Underground, Redwatch, Stormfront and Blood & Honour etc.

As I write, the Italian public prosecutors have initiated an investigation into the international neo-Nazi website Stormfront, which was founded by American Don Black, a former leader of the Ku Klux Klan and operates from Florida. Stormfront posted online a blacklist of ‘Italian criminals’, ie anti-racist organisations, Muslim and Jewish leaders, politicians, judges, lawyers, journalists, academics and priests who ‘look after immigrants’. The publication of the names occurred after a member of an online forum called Costantino posted, ‘We are accused of racism against immigrants, and that we hate them for no reason, but Italians too commit crimes. I want to prove that I do not hate foreigners, but that I hate some Italians much more. This is why I wish to open this debate and collect the names of Italians who commit crimes, who help immigrants and profit from this.’

In Nazi Germany, the prelude to extermination can be traced to attempts by the Nazis to establish who was part of the national community and who was not, through the Nuremburg Laws, for instance. Some eighty years later, as we enter 2012, we see that political parties, via a debate on national values and identity, are again treating as unpatriotic, or even subversive those who don’t sign up to the dominant narrative about core values. Anti-racist and victim support groups, in their daily attempts to help victims of racist attacks and to take up cases and force the police to act, educate the mainstream about the dangers a nationalistic discourse which defines any sign of difference as a threat.

As the German state is forced to admit that the NSU’s campaign of terror could have involved more than eleven murders, the words – Hoyerswerda, Solingen, Lübeck, Ludwigshaven, – spring to mind. If it wasn’t for anti-racist organisations in Germany who would remember those previous atrocities? The importance of independent monitoring lies not just in the daily activities of these groups. They are the repository of a whole history of racism and resistance. On its tenth anniversary, congratulations are due to Reach Out. But the next ten years will also be critical.

Related links

Read an IRR News story: ‘Germany: why did Marwa al-Sherbini die?‘

Organisation Against Public Discrimination

Never Again Association in Poland

In Iustitia in the Czech Republic

Asociaciòn Proderechos Humanos de Andalucia

Collective Against Islamophobia