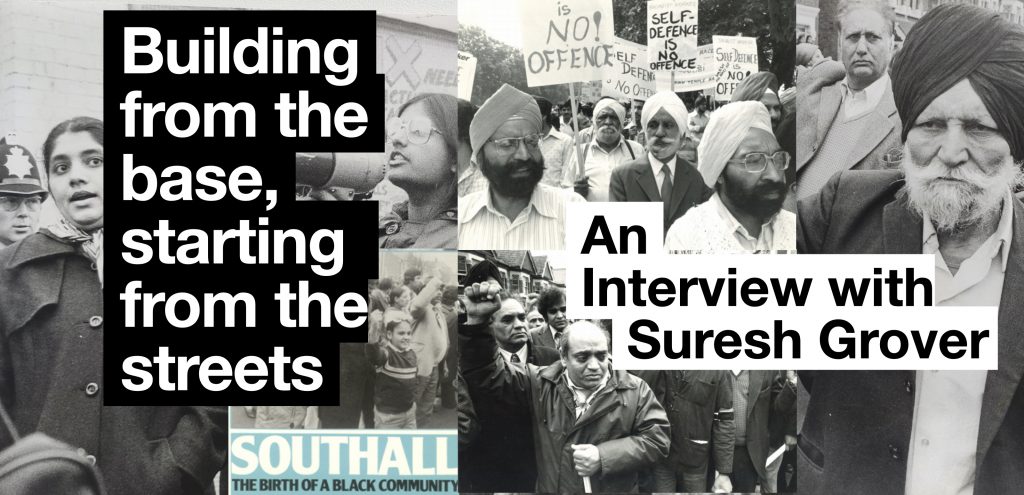

An interview with Suresh Grover.

Given the resurgence of interest in fighting structured racism in the UK, we publish an interview with Suresh Grover, one of the most intrepid fighters, who has kept going for over forty years, The Monitoring Group, the foremost community-based project taking up miscarriages of justice and effects of state racism on families and communities. This is an edited version of a full interview, ‘Baptised by fire’ carried out by Jasbinder S. Nijjar (to be published in Race & Class in January 2021) which challenges some of the popular misconceptions about the nature of the fight for racial justice.

The birth of Southall Monitoring Group

On 4 June 1976, Gurdip Singh Chaggar was murdered by racists in Southall, which resulted in youth rebellion and public disorder on the streets and the emergence of youth movements locally and nationally. In 1979, anti-fascist protester Blair Peach was killed by the Special Patrol Group (SPG). On 3 July 1981, we had coachloads of skinheads arriving for a music gig come into Southall and try to intimidate the community, which resulted in local youths organising and burning down the Hambrough Tavern pub where the musicians were to perform.

When we met in December 1981 to begin our discussions to form the Southall Monitoring Group, the national situation had also blown up. In January 1981, the ‘New Cross Massacre’ had happened, where thirteen people died in an unexplained house fire. There was also the Swamp ’81 police operation in Brixton in April that year, and, because of institutionally racist policing, SUS laws, and the attacks on communities, we saw uprisings or urban rebellions in over thirty cities and towns across Britain.[i] Several of us were also active in coordinating a national campaign for the Bradford 12 [who, during the self-defence of their community against a fascist incursion, had been accused of conspiracy to make explosives and cause explosions].[ii] The second phase of the hunger strikes by Irish Republican prisoners also had a deep impact on many of us.

So, it was an intense period of baptism by fire, where racism was at the fore and young black and Asian people were trying to build anti-racist resistance starting from the streets with communities at the centre. We wanted to establish and develop a self-organised and independent organisation that was embedded in Southall and had a progressive political and social outlook.

This meant that any new organisation or movement had to be inclusive and shaped by young people, women and workers in black communities. We were conscious of sexism and the overriding strength of patriarchy in our families, and looked towards black and South Asian feminist discourse to shape our thinking. From the outset, and mainly because we had witnessed the sexism and intimidation suffered by the founders of the Southall Black Sisters, some of whom we counted as friends and who remain so until today, we began supporting women-led self-organised groups and provided support to domestic violence victims. It is almost forgotten but, even before the establishment of Southall Black Sisters in 1979, there were Asian women’s groups active in Southall.

The birth of the Southall Monitoring Group (SMG) was influenced by the political and cultural landscape that existed around us. To be honest, we fought on the streets, we carried out legal defence and campaigning work, and we quarrelled and debated amongst ourselves to make sense of the political period we were living in. It was the fire in our belly that was shaping our politics and activism. When we sat in a damp room, during a bitterly cold winter, in front of a paraffin heater, with not much light, it was the need to organise against the violence of state-sanctioned and street-based racism that drove us to discuss the inception of the group.

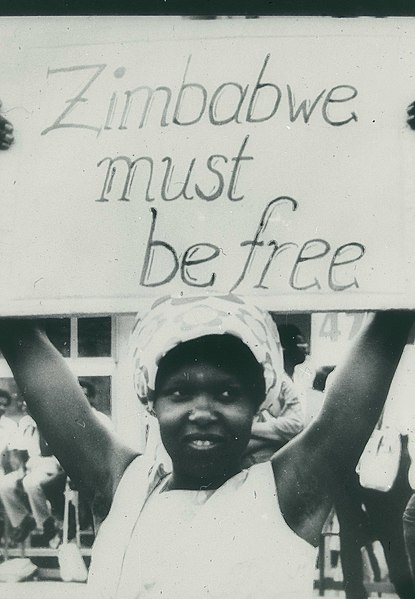

For us, the idea of monitoring police violence and actions came from the work of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in the United States. At that time, members of the Black Panther Party would follow police cars to observe the policing of black neighbourhoods. So, we took the concept of a monitoring group from the Black Panthers, and that is what we meant by monitoring. It is not the monitoring of data and analysis, but the monitoring of police racism, violence and misconduct. Also, the Black Panther Party’s efforts to link up with the poorest sections of the community, and to represent them politically, were a big influence on us. We learnt from their ten-point programme, and from their food programme, which showed us the importance of connecting political struggle with providing a service that could deal with daily effects of poverty as well as racism. The emergence of black politics and anti-racist mobilisation in Britain coincided with seismic political upheaval in South Asia, the struggles of which were also very prominent for us.

It was not like we did some sort of systematic analysis of all these struggles. But there was an understanding of them based on our own lived experience, in terms of how they were being waged, what their intensity was and where they were leading. And there was also absolute sympathy for them.

From 1981 onwards, there were multiple campaigns that took place which were key to our development. Among them is the Kuldip Sekhon campaign – Kuldip was a taxi driver killed in Southall in November 1988 after being stabbed fifty-eight times. The person who killed him was known as a young ‘fronty’. In other words, he was a racist who had been taking part in attacks on black and brown people in the area.

Kuldip Sekhon’s family wanted to call a demonstration on the day of his funeral, which took place on 31 January 1989. With the family, we managed to close Southall for half of the day after speaking to shop owners, schools, banks, bookmakers and so on. We also attracted four to five thousand people at the funeral, outside the local Dominion Centre. It was obvious to us that if we worked in a family-centred way, if we tried to enable justice, if we were true to people and explained what we did, providing you have the connections and are rooted in those communities, it is possible to do anything.

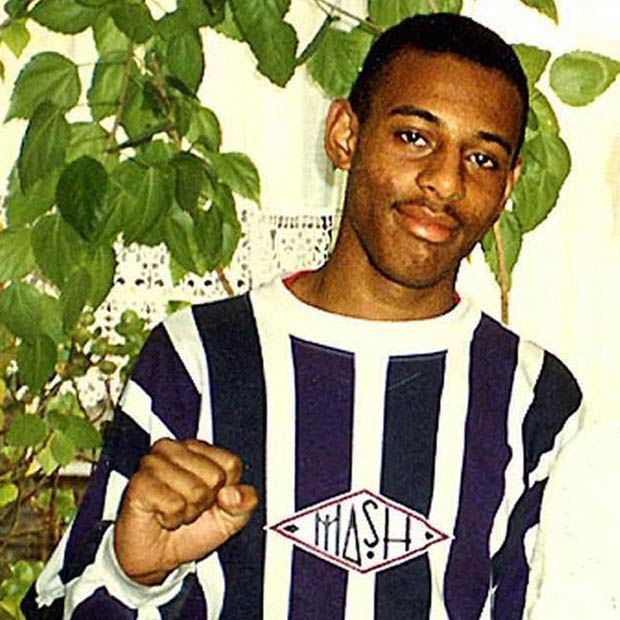

Following the Sekhon family campaign, in 1993, a relative of the Stephen Lawrence family approached me for assistance on developing a campaign.[iii] and we sustained that connection with the Lawrences from 1993 to 1999. And when the recommendations from the public inquiry came out, around a thousand families had contacted us nationally. We were not amazed by that, because we were coordinating other family justice campaigns, including those for Ricky Reel [who drowned following or during a racist attack in October 1997], Michael Menson [who was set alight by racists and died from his burns in January 1997] and others who suffered racism and then the reluctance of the police and criminal justice system to recognise what had happened and investigate thoroughly. But it showed us the large-scale lack of assistance that black and Asian families had faced, and the gravity of racism they had endured. It further confirmed to us that the litany of failures which the Lawrences had suffered were being experienced by other families on a broader, systematic scale.[iv]

As a response to this, we, along with others, created a national network following the recommendations in the Macpherson Report of the Lawrence Inquiry.[v] The first meeting attracted around 800 people from all over Britain – and we made a conscious effort to speak to every single family. It became obvious to us that we could not just call ourselves the Southall Monitoring Group, and that we had to have a national profile, so we changed our name to The Monitoring Group.

Cases into causes, causes into a movement

Three things describe our work. We are an advocacy agency, and advocacy is not just about advocating at an individual level. If possible, it is about changing the system that reproduces racism. We are concerned with addressing not only the impact of racism, but also the root cause of it. Otherwise, you are just firefighting all the time, and there are moments where we are doing that. But, for our work, recognising the politics of racism is critical. It means that when we work on a case of racial violence, or of police or structural racism, we are challenging the myth that black and brown people are the problem, rather than institutional racism. It also means that we do not see these cases as exceptional. The rule is that we live in a racist society and the families we work with are the victims of a systematic form of racism.

The second point is that we have never sought to patronise the families who come to us. We have always viewed them as individuals who have the power to change the broader conditions around them. What they lack is either an acknowledgement from the state, the response that the state should be giving, or, more importantly, the information and knowledge required to change the wider circumstances that have shaped their lived experience. So, for us, holding state agencies to account becomes pivotal to that process of change. We have always seen the families we work with as people who have the capacity to analyse, take part in decision-making, and generate momentum for not only addressing the injustices they have faced, but also understanding the wider political causes of them.

The third point is that if cases become causes, and causes develop into a movement, then victims become protagonists and the leading agents of change; and if you can create a grassroots movement and show a collective or united front to the state, the chances of making positive changes, even on a reform level, become greater; the alliances or coalitions that are built between families, communities and organisations are a vital step towards dismantling the structures that perpetuate racism. Coalition work allows collective thinking and discussion about making root-and-branch changes. That is the most difficult part. You can build causes and movements but dismantling and rebuilding the structures of society requires a much broader analysis.[vi] It is important to acknowledge that movements are not formed or developed simply by naming something as a movement. They are made up of a constellation of different political and economic forces which change over time. Any form of collective organisation and mass mobilisation must recognise and respond to these ongoing shifts in power.

The case of Stephen Lawrence

We were involved at different levels of the Stephen Lawrence campaign, beginning really from 1993, when we began working with the Lawrence family to revitalise the Stephen Lawrence campaign. The Southall Monitoring Group was part of the decision-making process regarding the private prosecution [of the alleged attackers that the Crown Prosecution Service had failed to charge]. Also, by the time we started this process, Stephen’s mother Doreen was working in the Southall Monitoring Group as a domestic violence worker, while his father Neville would come and assist, so that is when some of the meetings on campaign strategy took place.

When the public inquiry came about in 1998, we had further discussions with Doreen and Neville about what the campaign strategy would be. On the first day of the inquiry, not many people attended, perhaps because people thought the inquiry would be sterile. Nobody knew what it would bring. The Lawrences decided that we had to become more active, which led the Southall Monitoring Group to create a Stephen Lawrence family campaign afresh by including new people.

We were conscious of the need to fill the space and bring community experiences to the hearing. It meant making the public gallery become active and reflect a community’s experience in the court setting. It was not simply about listening at a micro level on a specific case. Macpherson and his advisors were conscious that the public gallery was full, and we wanted them to see that the Lawrence case was not exceptional, and that it was a pattern of other systemic failings that had taken place. We managed to get scores of families, activists and the general public to attend, and there was no turning back once we had reignited the campaign. We also had international people and activists who had been part of anti-racist struggle or black struggle coming and visiting. Fredrika Newton, the widow of Huey P. Newton, turned up with David Hilliard.

The second thing was that it was obvious the legal team would be restricted in what they would say. So, we encouraged the public gallery to become more active and outspoken – we wanted it to be noticeable, to be seen to be reasonable, but also to not stand the bullshit that was being said by police officers as justification for their failures. It led to the creation of the Public Gallery Committee, which would issue its own statements, independent of the Stephen Lawrence family campaign. It was a riveting period because people who came to the inquiry, but who were not necessarily connected with the Lawrences, became a part of it.

The third thing is that we put ourselves at the disposal of the Lawrence family. We would have done anything for them, because we thought they represented the public face of a massive tragedy, whose characteristics – racial violence and police failures – had impacted on black and brown communities in Britain for decades. We had the resources and experiences to develop campaigns, given that we had experienced racial violence personally, and because we had been part of a larger struggle against state racism.

Reflecting on the fight against racism today

Racism has always been, and remains, a political problem. The state is the foundation, the arbiter and developer of racism, including racism in its popular or individualistic forms. If you lose sight of the politics of racism, it becomes an issue of prejudice between different people. I am not saying that day-to-day racist interactions are not relevant or important. But you cannot challenge everyday racism unless you challenge the source of that racism, which is the state. It is state policies and laws that set the context for, and create new ideologies and forms of, racism.

We also know that racism has a historical dimension. It has existed for centuries and comes in many forms, which means that, as a political problem, it is never static. But, the racism of today is different to the racism that existed during the industrialisation of countries and colonialism. Today, we have the racism of neoliberalism, which has led to the mass exodus of migrant populations from their home countries because of local and foreign economic policies, the devastation of industrial complexes by multinational corporations, famine, regime change, and so on.[vii]

There is no question that the legacy of the Stephen Lawrence inquiry is its use of the term institutional racism. But now we are witnessing a concerted effort by people who have never really accepted the implications of institutional racism existing, to create newer definitions of racism. These new definitions, that are rooted in concepts like unconscious bias and hate crime, personalise and depoliticise racism.[viii] They create a hollow definition of racism. I think this has been a deliberate and systematic manoeuvre, because the consequence of acknowledging the existence and prevalence of institutional racism is structural and systemic change. To avoid this, state agencies have done everything possible to dismantle Macpherson’s definition of institutional racism, regardless of how accurate or full it was.

It is a devastating indictment of our times, especially when considering that race and class disparities expressed through Covid-19, the disproportionate use of stop and search on black people – even during lockdown – and Black Lives Matter have shown how institutional racism still exists. Yet you have prime minister Boris Johnson creating a new commission on racial and ethnic disparities, which is meaningless since it involves people who are deniers of institutional racism and have got together to redefine, re-strengthen and re-legitimise an attack on the notion of institutional racism, without ever addressing its realities. That is also why the Metropolitan Police commissioner, Cressida Dick, told the Home Affairs Committee that institutional racism is not a helpful term or concept.

We need to reclaim anti-racism with its political and historical roots. Both the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles of the past, and the lived experiences of communities today, must be central to anti-racism, so that we can make connections between historical and contemporary phases of racism. I also think we must take on the far Right with a broader analysis that encompasses anti-racism rather than just anti-fascism. We must understand that the fight against institutional racism is part and parcel of defeating the far Right and fascism.

The Left has always dealt with fascism, but not with structural racism. Part of that is because it must question itself, and because the labour movement, including the Labour Party itself, does not know how to deal with systemic forms of racism. As a result, it fails to dismantle the structures that perpetuate racism. Labour has no policy or strategy on how to deal with institutional racism in the police force, the criminal justice system, or anywhere else, and it is unlikely to come for the next five years, which leaves us in a very dangerous and alarming situation.

I believe that the future is black, by that I mean politically black. There is enough courage at an individual level, enough resilience at a community level, and enough vision at a global level, in terms of anti-racist and anti-colonial struggle, for us to unite, establish strong alliances and reshape the future. We are seeing the emergence of a younger generation that perhaps is not baptised by fire like my generation was, but they are willing to grapple with the nature of state racism and expose it more diligently than we did, using different tools. They are a generation that do not see themselves as going back to any other country – Britain is the country they wish to transform.

Footnotes

[i] For details of these ‘riots’ and Swamp ’81 see Notes and Documents in Race & Class, 23 no. 2/3 (1981), pp. 223-232.

[ii] For more on the Bradford 12 case, see https://libcom.org/history/bradford-12-self-defence-no-offence

[iii] Stephen Lawrence was stabbed to death by a white racist gang on the street in Eltham, south London on 22 April 1993. When the Crown Prosecution Service decided in July 1993 there was not enough evidence to charge those arrested for the murder, the family brought the first private prosecution for murder in modern legal history. It failed. However, after a constant family campaign for justice, on 3 January 2012, two of the gang were found guilty of Stephen’s murder. But before that conviction, agitation by the family and campaigners had pressured the Home Secretary to hold a public inquiry into ‘matters arising from the death of Stephen Lawrence and identify lessons to be learned from the investigation and the prosecution of racially motivated crimes.’ Sir William Macpherson reported in February 1999, finding for the first time in an official inquiry, the evidence of institutional racism in the police.

[iv] For an account of cases taken up by The Monitoring Group see http://www.tmg-uk.org/history-of-tmg/

[v] The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Report … chairman Sir William Macpherson (London, Home Office, 1999) CM4262.

[vi] See for discussion of such building Jenny Bourne, ‘Movement for Black Lives: an interview with Barbara Ransby’, IRR News, 24 July 2020, https://irr.org.uk/article/movement-for-black-lives-an-interview-with-barbara-ransby/

[vii] See A. Sivanandan, ‘Poverty is the new Black’, Race & Class 43, no. 2 (2001), pp. 1–5.

[viii] See J. Bourne, ‘Unravelling the concept of unconscious bias’, Race & Class 60, no. 4 (2019), pp. 70-75.