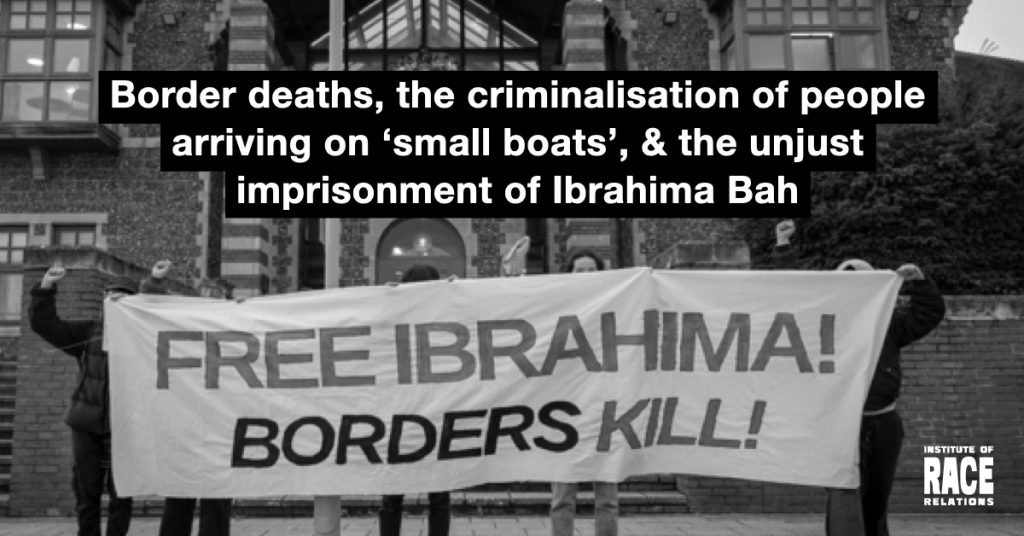

On Monday 19 February, Ibrahima Bah, a young person from Senegal, was found guilty by a jury of ‘facilitating a breach of immigration law’, and four counts of manslaughter by gross negligence. This is the second time he was hauled before a jury to relive the traumatic events of that night, as the first jury in July 2023 failed to reach a unanimous verdict. He had been identified on 14 December 2022 as having steered a dinghy which was shipwrecked in the Channel. Four people have since been confirmed dead, and an estimated five more are still missing and unidentified over a year later. On 23 February, Ibrahima was sentenced to 9.5 years imprisonment.

Across both trials, Ibrahima consistently denied wrongdoing, and maintained that he drove the boat after being threatened and assaulted by those organising the crossing. In sentencing him, Mr Justice Johnson recognised that Ibrahima ‘played no part in the organisation of the trip. You did not coerce other passengers. You had no control over the choice of vessel or the lack of equipment. You took on the role of pilot because you were asked to do so and because it was your only chance of getting to the UK. You did not secure any financial gain, other than avoiding the payment that would otherwise have been necessary to secure a place on the boat […] You were one of the last to leave the dinghy. After you left, you sought to help others, including your friend Mr Allagi who, tragically, died before your eyes’. Johnson recognised that there remains some doubt around Ibrahima’s age. All survivors have subsequently made asylum claims in the country.

As the court heard during his trial, people suffered and died in this way because they had no other means through which to reach the UK. The young Ibrahima is being held up as a scapegoat for deaths caused by the border and its securitisation. Alarm Phone has pointed to the fact that the UK-French border is rapidly becoming more deadly precisely because of the British government’s ‘Stop the Boats’ agenda. ‘Increased funding for the French has meant more police’, it argues, ‘more violence on the beaches, and thus more of the dangerously overcrowded and chaotic embarkations in which people lose their lives’. The organisation points to similarities in the circumstances surrounding more recent shipwrecks on 12 August 2023, 15 December 2023 and 14 January 2024, which all happened shortly after dinghies left French beaches in chaotic launches due to police involvement. The tragic events of 28 February 2024, in which three more people lost their lives in French waters, may be the latest deadly incident in this trend.

While the dinghy Ibrahima was travelling on in December 2022 did travel further from the French coast, questions have been raised in commentary and legal proceedings, about failures in the responses of both British and French agencies. Alarm Phone and LIMINAL concluded that ‘the shipwreck and subsequent loss of life occurring on the 14th of December was the result of many factors for which no one can be individually held responsible’. Their careful analysis highlights the lack of rescue effort from the French side, and quotes survivors saying that the fishing crew which eventually rescued survivors “ignored us initially, until we got close enough”.

Ibrahima’s conviction, in individualising the blame for the deaths that night, attempts to obscure the structural conditions which force people to make such dangerous journeys and increase the likelihood of death when making them. Increased securitisation pushes people into more and more dangerous routes. As journalist Maël Galisson writes in his recent detailed investigation of 391 deaths which occurred at the Anglo-French border between 1999 and 2024, despite the ‘concrete barriers, barbed wire, video surveillance, police and gendarmeries, patrols on horseback, motorcycles, all-terrain vehicles, and drones […] the dead keep piling up’.

Ibrahima is the first to be convicted of manslaughter in the UK for his role in piloting a boat on which people sadly drowned. He is not, however, the only person to have been charged with or convicted of the second offence: ‘facilitating a breach of immigration rules’, or of his own ‘illegal arrival’. These offences were expanded and created respectively by the Nationality and Borders Act (2022) (NABA), which removed legal barriers to the prosecution of people identified with their ‘hands on the tiller’ raised in appeals in 2021.

There has been an ongoing and sustained effort to construct people crossing the Channel as illegal. Yet, before the NABA, the act of crossing the Channel to seek safety was not, in fact, against the law. To quote Nicolas de Genova, ‘A migrant becomes “illegal” only when legislative or judicial measures make certain migrations or certain types of migration illegal, in other words when they “illegalise” them’.

My recently published research report, published by Border Criminologies and the Oxford Centre for Criminology, and informed by the work of Captain Support UK, Humans for Rights Network, and Refugee Legal Support, details both the extent of these prosecutions and the impact they have on individuals affected.

According to FOI data, from 1 July 2022 to 31 October 2023, 253 people were convicted of ‘illegal arrival’ off a ‘small boat’. 49 people were charged with ‘facilitation’, including two men for bringing their children with them on the dinghy. As of 31 October, seven of these had been convicted. Those arrested for ‘illegal arrival’ were usually either identified as steering the dinghy, or as having a ‘previous immigration history in the UK’. This second group is defined broadly, and I observed instances of people being identified for arrest for having previously applied for a business or family visit visa, or for re-entering after being exploited and trafficked out of the country.

As other commentators have argued, including the UN Refugee Agency, there are serious questions about the compatibility of this prosecutorial strategy with the Refugee Convention, as well as other instruments of international law, which prohibit the penalisation of refugees for arriving irregularly, or for facilitating the arrival of others, in the course of seeking safety for themselves and each other.

The Home Office argues that criminalising people for crossing is a necessary ‘deterrent’. Similarly, in court, sentencing decisions are justified by ‘the need to deter others from placing their own and others’ lives at risk’. As previous work by researchers at the University of Oxford has shown, however, there is no evidence to support the logic of ‘deterrence’: other factors are usually more important in people’s decisions to move, and those on the move often do not have full information about the UK’s policies. This is supported by the Home Office’s own analysis, previous commissioned research, and by the Court of Appeal in a recent case. From my research, people appearing before the court for these new offences were often shocked and unaware of why they were there, demonstrating very little or no awareness that criminal prosecution was possible. Lawyers reported spending considerable time explaining the situation to their clients, who were often confused and extremely distressed by their arrest.

In adopting this kind of ‘humanitarian’ logic, the state forecloses the possible ‘solutions’ to those which intend either to maim (through eg, barbed wire on the beaches) or punish and incarcerate (see Polly Pallister-Wilkins). Instead of ‘deterring’, then, the policy causes considerable harm to many, most of whom, in all likelihood, cannot be removed from the country. Among those arrested are people from very high asylum grant rate nationalities, as well as victims of trafficking, torture, and to date, 15 identified children with ongoing age disputes.

The criminalisation of people for crossing borders in search of safety will not ‘stop the boats’, or the inevitable deaths associated with these dangerous crossings. These prosecutions, and the scapegoating of individuals for deaths which are systemic to the British border regime, must end.