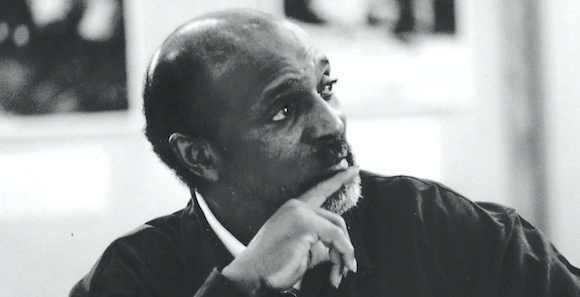

Below we publish tributes to Cedric Robinson.

Tom Denyer

As intellectual careers go, Professor Cedric Robinson’s serves as a textbook. His first priority, teaching, relied on close, generous engagement with the mind of the individual student. He still found time for disciplined, objective, assiduous research and writing. His genuine interest in the work of his colleagues elevated many projects. Through diverse media he took his guidance and discoveries into the public forum.

Yet his really good politics dominate my memories. Those of us whose lives wander through the twists and turns of the workers’ movements often despair. It turns out that not everyone is on our side; and some who are we wish were not. They never deterred Professor Robinson. He scattered them, chaff before the wind.

When he and I differed over tactics and ethics he clarified my errors, and readily conceded my occasional correctness.

Someone else will have to chronicle all his escapades. The encounter with Miles Davis in an Oakland club. The encounter with the House Unamerican Activities Committee in San Francisco. The commencement address that reminded his students’ parents that casual use of racial epithets sometimes had unpleasant consequences. The Gang of Seven’s encounter with university corruption.

His work will stand the test of time, and his life will continue to inspire.

Robin D. G. Kelley Reflects On Cedric Robinson

‘Scholarship Is Not Dispassionate, But It Is Deliberate And Systematic’

Many colleagues are taken aback when I tell them that a political scientist taught me how to be an historian. Although this isn’t entirely accurate since Cedric Robinson was no ordinary political scientist—his Stanford University doctoral dissertation, ‘Leadership: A Mythic Paradigm’ (1975), was essentially a critique of his discipline.[1] His work has had a profound impact in the fields of Sociology, Anthropology, Political Economy, Film Studies, Cultural Studies, African and African Diaspora Studies, and of course, History. No discipline could contain him. No geography or era was beyond his reach; he was equally adept at discussing Ancient Greece, England’s Middle Ages, or early anticolonial rebellions in Southern Africa.

But rather than discuss his scholarship, I want to say something about his extraordinary role as a mentor. In 1984, he agreed to serve on my exams and dissertation committee after I cornered him at a meeting of the African Studies Association in Los Angeles. He readily agreed and I began a regular trek from UCLA to UC Santa Barbara about every other week to meet with him. When I mustered the courage to send him an early draft of an essay on African Americans in the Communist Party, he sent back three single-spaced pages of humbling criticism in the form of a letter dated June 21, 1985. After taking me to task for ‘haphazardly’ treating the historiography, he advised me to ‘temper your literary voice’ and stop editorializing. Of course, I was trying to write like C. L. R. James, W. E. B. Du Bois, Walter Rodney, and Karl Marx, full of sly humor and sarcastic digs at the ruling classes. Cedric wasn’t impressed: ‘From what little I know of the profession and particularly the department at UCLA, neither sarcasm nor direct political charges will be tolerated by almost any reviewing committee you might construct. Save your judgments for the published version of your work not the dissertation. Scholarship is not dispassionate, but it is deliberate and systematic in the way it reconstructs an event. Try not to indict for racism when the materials will allow you to ‘discover’ it.’ Sage advice, to be sure; I’ve spent three decades repeating his words to my own students.

But rather than discuss his scholarship, I want to say something about his extraordinary role as a mentor. In 1984, he agreed to serve on my exams and dissertation committee after I cornered him at a meeting of the African Studies Association in Los Angeles. He readily agreed and I began a regular trek from UCLA to UC Santa Barbara about every other week to meet with him. When I mustered the courage to send him an early draft of an essay on African Americans in the Communist Party, he sent back three single-spaced pages of humbling criticism in the form of a letter dated June 21, 1985. After taking me to task for ‘haphazardly’ treating the historiography, he advised me to ‘temper your literary voice’ and stop editorializing. Of course, I was trying to write like C. L. R. James, W. E. B. Du Bois, Walter Rodney, and Karl Marx, full of sly humor and sarcastic digs at the ruling classes. Cedric wasn’t impressed: ‘From what little I know of the profession and particularly the department at UCLA, neither sarcasm nor direct political charges will be tolerated by almost any reviewing committee you might construct. Save your judgments for the published version of your work not the dissertation. Scholarship is not dispassionate, but it is deliberate and systematic in the way it reconstructs an event. Try not to indict for racism when the materials will allow you to ‘discover’ it.’ Sage advice, to be sure; I’ve spent three decades repeating his words to my own students.

Cedric demanded that I pay more attention to political economy, to the various racial, ethnic and national struggles taking place within the Communist Party, to its deep distrust of ‘petit-bourgeois nationalism,’ and to why the Party seemed vulnerable to the kind of vulgar Marxism that substitutes ‘economism … for historical analysis’ and takes the revolutionary force of the proletariat as an act of faith. He listed many reasons why he thought this was the case—from the canonization of the Bolshevik Revolution to the fact that bourgeois nationalism defeated or undermined radical movements in Western Europe, leaving fascism and national imperialism in its wake. But the explanation that floored me was Cedric’s almost off-hand remark that the largely foreign-born radical intelligentsia that dominated the Party knew very little about U.S. history and was unaware that ‘the South had been the intellectual vanguard of American society, and as Du Bois had demonstrated in Black Reconstruction, Black workers had led many of the radical movements before the 1870s.’ Communists could not have known this, he added, since the Party did not have theoreticians of the caliber of Oliver Cox, Du Bois, James, Frantz Fanon, or Amilcar Cabral.

Cedric kicked my ass 31 years ago. He continued to kick my ass, lovingly but relentlessly pushing me to be the historian I’m still trying to become. This is why I cherish that letter, and why I love Cedric J. Robinson.

[1] He published a slightly revised version of the dissertation titled, The Terms of Order: Political Science and the Myth of Leadership (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1980)

Lawrence Ware

‘Cedric Robinson, Author of Black Marxism, Died This Month to Little Fanfare, but Not Before He Changed My Life’

No great obituaries were written about Robinson’s life when he passed away on June 5. But it’s not an overstatement when I say that Robinson’s work and unapologetic love of black people not only shaped me but also showed me that my culture had philosophical importance.

I know that many are given to hyperbole upon learning that a person they revere has gone to be with the ancestors, but it is not an overstatement to say that Cedric Robinson, who passed away on June 5, truly changed my life.

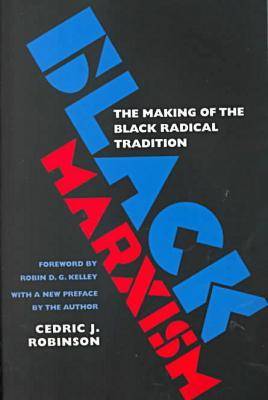

I was a graduate student in 2006 when I came across a book with a black background and the words ‘Black Marxism‘ written in blue-and-red block letters on the front. The title surprised me because, unlike now, most of the progressives I’d met were white men and women given to tie-dye shirts and arguments about the differences between Trotskyism and Leninism.

I was a graduate student in 2006 when I came across a book with a black background and the words ‘Black Marxism‘ written in blue-and-red block letters on the front. The title surprised me because, unlike now, most of the progressives I’d met were white men and women given to tie-dye shirts and arguments about the differences between Trotskyism and Leninism.

The history of black Marxism intrigued me. I knew I couldn’t have been the only one, but I was unaware that I was part of a lineage that combined academic rigor with social activism. A. Philip Randolph, W.E.B. Du Dois, Richard Wright—they became more than historical figures. They were my intellectual family. They gave me the courage to fully be who I was called to become: a black man who placed my unapologetic love of black people in dialogue with my commitment to economic justice.

This is the gift of great scholarship, the reason that black intellectual genealogies are important. They teach us that history is a living, breathing thing—something with which we can wrestle and to which we can contribute. Black history is more than a series of firsts. It’s also groundwork laid by intellectual giants that beckons us to complete the effort or, at least, build upon it.

In philosophy, I was required to read books written exclusively by white men. I wondered if I had what it took to contribute, if my culture was of philosophical import. Cedric Robinson informed me that I mattered, that my culture mattered. I had something to contribute, and his example challenges me still.

Born in Oakland, Calif., Robinson completed his undergraduate work in anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. He achieved his Master of Arts and doctorate at Stanford University in political theory. He wrote many books of note, Black Movements in America and An Anthropology of Marxism among them, but Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition is his magnum opus—the text for which he will be remembered.

Charting black Americans’ engagement with Marxism is no simple task. To start with the version of Marxism found in Europe and slowly and meticulously show the way black thinkers dialectically developed a version of the ideology that adhered to the basic principles of economic egalitarianism found in almost all explications of Marxism but differed in how it placed racism in dialogue with the conceptual lens Marx provided was brilliant, necessary and courageous. It’s a lesson that many progressives need to learn.

Supporters of Bernie Sanders were surprised by the candidate’s cold reception from black voters. They thought that Sanders’ message of economic reform would be sufficient to make the senator from Vermont appealing to that constituency. What these supporters underestimated was the degree of suspicion black Americans have historically had regarding attempts to address racial ills using socioeconomic cures.

A black working-class child has to contend with economic inequality and racism. Fixing the former will not eradicate the latter. If economic egalitarianism is achieved, an officer may still gun me down in the street because I am black. Sanders’ persistent pivot to class was part of his undoing with black voters. A close reading of Black Marxism would have let him know what to expect.

Before the movement for black lives made black radicalism cool for millennials, Cedric Robinson did the work of excavating an intellectual history we rely upon today. No great obituaries ran in the New York Times. Few even noticed his passing. But the work of Robinson continues to inspire black scholars whose work intersects with the Marxist tradition. He did it because he loved black people, and his work speaks to us still.

(Reproduced from The Root)

Critical Resistance

This past week, we were saddened at the loss of two incredibly powerful figures. Cedric Robinson and Muhammad Ali were among the most highly revered and admired individuals for wide ranging reasons. But what they shared in common was an unwavering commitment to Black struggle and standing against the oppression of Third World people everywhere. Their passing provides an opportunity, therefore, to reflect and to honor their work, the risks they took, and the spirit they exuded. May their passing reinvigorate our will to resist and sharpen our understanding of what we are fighting against.

Cedric Robinson’s work has deeply informed the way racial capitalism is understood and fought against, including Critical Resistance’s analysis of and struggle against the prison industrial complex. His singular contributions to Black radical thought and Third World liberation as a scholar and revolutionary thinker continue to empower radical movements internationally. At CR, we remember Cedric Robinson as we continue to fight for abolition and towards liberation. These words from Robinson in 1999 ring more true than ever today, foregrounded by hope and revolutionary spirit:

‘But the world is dynamic, constantly changing, constantly creating new possibilities. All over the US, Black Radicalism is manifesting itself in urban churches, in theory and practice. What will be the next phase, when the rule of law becomes transparently farcical, the Christian right achieves its fascist perfection, and the State acquires a predominantly carceral posture towards the majority of Blacks, Latinos, etc.?’

Muhammad Ali also shared this uncompromising commitment. At a time when it was unpopular and detrimental to one’s own livelihood, Ali sacrificed his unparalleled boxing career by boldly refusing to be drafted for America’s imperialist war in Vietnam. He knew very well that his enemy was American empire and white supremacy (which the mainstream conveniently glosses over as it whitewashes his legacy), and identified with the Vietnamese and those fighting for self-determination.

In his own sharp words:

‘I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such a stand would cost me millions of dollars. But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom, and equality.’

CR joins many honoring the enormous legacies of both Robinson and Ali, and will continue to draw inspiration from their contributions to the struggle for freedom.

Henry T. Yang, Chancellor (University of Califorina, Santa Barbara)

I am deeply saddened to share with you the news that our colleague and friend Professor Cedric James Robinson passed away on the morning of June 5th. My wife, Dilling, and I were able to visit with his wife, Elizabeth, at their home later that day and offer our condolences in person.

A community and political activist, Professor Robinson joined UC Santa Barbara in 1978, becoming the Director of our Center for Black Studies Research and a faculty member in our Department of Political Science, where he served as Chair from 1987 to 1990. In the mid-1990s, he moved to our Department of Black Studies, serving as Chair from 1994 to 1997. He took on several leadership roles in addition to his chairmanships, including serving on search committees and holding Academic Senate positions. He retired in 2010, but continued to teach and mentor students. Prior to joining our campus, Dr. Robinson had held faculty appointments at the University of Michigan and the State University of New York at Binghamton.

In 1980, Professor Robinson and a student started Third World News Review on our campus and community radio station, KCSB. The program offered a dialogue on social, political, and cultural events around the world from sources other than the mainstream media. The show became available on public access television a few years later, and remained on the air for more than 30 years. Cedric’s wife, Elizabeth, has also been an important part of our campus community, previously serving as KCSB Advisor and Associated Students Associate Director for Media. She retired in 2012 after 31 years with the University.

Professor Robinson wrote broadly on subjects ranging from political thought in the United States, Africa, and the Caribbean to Western social theory, film, and the press. He authored several highly regarded books, including The Terms of Order (recently republished after being out of print for decades), Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, Forgeries of Memory and Meaning, and An Anthropology of Marxism (originally published in the United Kingdom but slated for U.S. publication in the next year). He received a B.A. in social anthropology from UC Berkeley, and completed his M.A. and Ph.D. at Stanford University in political theory. His fields of interest were modern political thought, radical social theory in the African diaspora, comparative politics, and media and politics.

Professor Robinson was a person of tremendous passion whose teaching, research, and activist engagement inspired and challenged those in our campus community and far beyond. I remember Cedric as a campus citizen, leader, and mentor who was soft-spoken, calm, thoughtful, and kind, and never without a sense of humor. Our hearts go out to Elizabeth; their daughter, Najda; their grandson, Jacob; and to the rest of their family and many friends. Cedric will be dearly missed by all of us at UC Santa Barbara.

In honor of his memory, our campus flag will be lowered to half-staff on Thursday, June 16. A memorial service will be held that same day at 1 p.m. at Welch-Ryce-Haider on Ward Drive.

Professor Gus John

Devon C. Thomas – The Griot

Related links

Free collection of Race & Class articles – Cedric J. Robinson and the Black radical tradition

Although I met Cedric briefly at one of his London lectures, I really knew him only via his work – but what work, what scholarship! I first read ‘Black Marxism’ in the 1980s when trudging up and down the country, distributing Zed Books’ catalogue. It has remained on my shelves for the past thirty years and I have returned to it many times for inspiration and as an example of how to trace hidden genealogies of political thought and activism. It was not his only important work but in that book he addressed, through historical analysis, the challenge of how Marxism might be stretched by those who had experienced capitalism as the effect of European conquest, a question on which classical Marxism largely remained silent. One of the great works of the black Atlantic. He will be missed but his influence continues.