Matt Carr reflects on the complicity of Britain and France in the horrific situation for migrants in Calais.

For millions of British tourists, Calais is a gateway for continental driving holidays and the pleasures of the Summer. For others it’s a city of designer shops, of the massive Euroshopping mall Cité Europe, where the Daily Mail and P&O ferries were offering £1 fares for foot passengers to do their Christmas shopping last year.

There is of course another Calais, the city that has become a trap and another of the world’s border bottlenecks, where Europe’s unwanted migrants come each year in the hope of getting onto a truck that can take them to the UK. Most of them have endured astonishingly harsh and difficult journeys to escape poverty and political, religious or gender oppression, only to find themselves living in derelict squats, tent camps or on the streets, constantly watched, harrassed, arrested and often beaten by the contingents of the Republican Security Companies[1] who have been deployed there especially to make their lives hell.

Since Calais is part of Europe, and Europe is a civilised and humanitarian place, the Calais authorities don’t let the migrants starve. Each day charities feed them in the food distribution centre by the docks, and in winter some of them are allowed into a shelter during the coldest months, and sometimes they are provided with showers to prevent them becoming a public health problem.

In the meantime they spend their time waiting for the opportunity to get onto a truck and cross the channel. Some succeed, otherwise they wouldn’t bother trying. Others are injured or killed.

I’ve been to Calais three times in the last four years to write about the migrants in the city and the local people who help them. I’ve watched that war of attrition intensify from its beginnings in early 2010. That year I watched the French police take away blankets from homeless migrants in what the deputy mayor Philippe Mignonet described to me as a ‘cleaning operation’. The last time I was there was in 2012, when I was physically threatened and nearly attacked by a group of stoned migrants and a French man who was as zonked as they were, because they didn’t like journalists.

I couldn’t really blame them too much. Conditions for migrants in 2012 were harsher than they were in 2010. The desperation and tension were obvious, the competition to get onto the trucks was fiercer, and most migrants had no reason to feel particularly enamoured of journalists whose coverage was often hostile and wilfully dishonest.

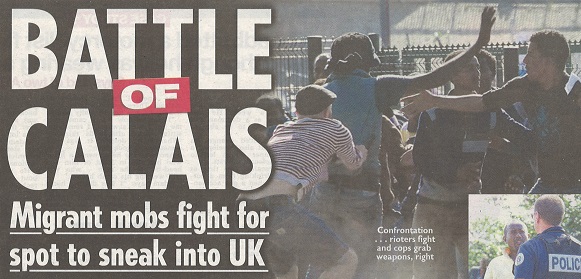

So I wasn’t surprised by last week’s reports of violent clashes between Sudanese and Eritrean migrants at the food distribution centre – or the use of rubber bullets by the French police to suppress them. Calais has always gnawed away at the British tabloid imagination, and last week’s events have sent Fleet Street’s finest scurrying across the channel in search of French perfidy, migrant ‘benefit tourist’ parasites, and the immigrant invasion.

There was the Daily Express, warning that migrants in Calais might bring Ebola to the UK. And inevitably, there was the Daily Mail, a newspaper that bears more responsibility than any other for creating and fuelling the fears and prejudices that underpin the brutal ‘migration management’ regime in Calais, shedding crocodile tears and promoting myths in equal measure, with a story carrying this byline:

As Eritreans and Sudanese riot in Calais over the best spot to jump onto lorries bound for Britain, one mother of a little daughter says ‘Nothing will stop us getting to your schools and hospitals!’

This is the kind of threat guaranteed to make a Mail reader’s blood run cold, even though I find it difficult to imagine that any migrant would say such a thing. Reading further down the story, it turns out that the Eritrean mother interviewed by the Mail’s ‘reporter’ Sue Reid didn’t in fact say any such thing. Her actual words, in regard to her daughter, were: ‘I want her to have an education. She also needs help from your hospitals because she has asthma and a back problem.’

One of the favourite tabloid motifs in discussing Calais or migration in general is the idea that Britain is a ‘soft touch’, whose foolhardy generosity makes the country uniquely attractive to undocumented migrants. To make this point, Reid includes the following quote from a group of Calais migrants on the Internet:

If we ask for asylum in France, they make us wait in the streets. In England . . . they give us a house, we have access to a school, to proper food and a dignified life.

The actual quote comes from an open letter written by the residents of the ‘fort Galoo’ squat in Calais posted on the Calais Migrant Solidarity website. The original translation from the French goes like this:

If we ask for asylum in France, they will make us wait many months before we can have access to a shelter, whereas in England, in Germany, in Holland, they give us a house, we have access to school, to proper food and dignified conditions of life.

Just a little different, but such small differences have consequences. Reid’s piece shamelessly recycles the same anti-migrant prejudices and stereotypes that have been repeated so often by the British press, and such representations have been crucial in the gutless collusion of Britain’s political class in the horrendous treatment of migrants in Calais.

Philippe Mignonet once told me that the situation in Calais is Britain’s fault, and the tabloids have reported similar statements last week with their usual outrage. But, though it doesn’t excuse what his administration has been doing, the deputy mayor is partly correct.

The main reason why migrants are trapped in Calais is because they want to come to Britain, but Britain doesn’t want them and won’t acknowledge them and expects France to do the dirty work on its behalf. The result is an unacknowledged policy of deterrence in which both the British and French governments are complicit. It is intended to make life in Calais as harsh for migrants as possible, without actually killing them, in the hope that they will stop coming.

Twelve years after the closure of the Sangatte reception centre, and five years after the demolition of the Calais migrant ‘jungle’, that policy hasn’t worked. When I was last there the numbers of migrants in Calais were estimated in the low hundreds. Now there are supposed to be 1,500.

Clearly these numbers are not dependent on the ongoing repression in Calais, but on shifting circumstances outside Europe. Many of the new arrivals are Syrians – a nationality that the British government regards as ‘good refugees’. Until recently, Britain was preparing to bomb Syria in order to save its population from tyranny. In Calais, Syrians are no longer worthy of salvation but only of exclusion and the policeman’s truncheon.

All this ought to shame and disgrace us, but politicians, the tabloid press and the public have managed to make it seem necessary and normal. And until that changes, and until we wake up to the poisonous politics and essential inhumanity that underpins contemporary ‘migration management’, Calais will remain one of the most brutal of Europe’s ‘hard borders’ – and a microcosm of the twenty-first century’s savage and racialised divisions of wealth, power, and lifestyle.

most of these are economic migrants not genuine people fleeing atrosities how we weed out the genuine is a big ask now they know how they must live in these camps return travel tickets should be given