A recent community campaigning book from France on deaths in police custody shows just how alarmingly similar the French experience is to that in Britain.

On 21 August 2014, Abdelhak Goradia (51), an Algerian undocumented migrant, died in a police van on his way to Roissy airport, near Paris, to be deported. A police spokesperson initially said that he had died of a cardiac arrest in the back of the van, claiming that a police officer had unsuccessfully tried to revive him. However, the post-mortem showed that Goradia had died from choking on his own vomit, and those close to him who saw his body said that there were one or two bruises on his face that they were unable to account for. For now, what is known is that Goradia, the father of a 6-year-old boy, lost his life in that van with police officers.

A chronicle of police impunity

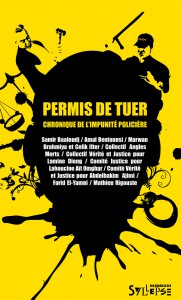

It is this struggle to uncover the truth and for justice (and ‘struggle’ here is no exaggeration) that an illustrated 200-page book entitled Permis de Tuer: chronique de l’impunité policière (Editions Syllepse, Paris, 2014) documents. Edited by the Collectif Angles Morts, a group involved in the struggle against police crimes and violence, it consists of essays by and interviews with activists and loved ones of those who have died during or after encounters with the police in France. The parallels with the experiences recorded in Dying for Justice, the recent report from the IRR on deaths in custody in the UK, are telling. While the Collectif is unable in the introduction to give an accurate number of those who have died in police custody, the groups estimate that hundreds have died over the past three decades since 1981 (the abolition of the death penalty in France), averaging around ten deaths a year. A large proportion of the deaths, and the deaths that the Collectif focuses on, are those of young, second-generation Arabs and Africans, often living in the Parisian banlieues.

It is this struggle to uncover the truth and for justice (and ‘struggle’ here is no exaggeration) that an illustrated 200-page book entitled Permis de Tuer: chronique de l’impunité policière (Editions Syllepse, Paris, 2014) documents. Edited by the Collectif Angles Morts, a group involved in the struggle against police crimes and violence, it consists of essays by and interviews with activists and loved ones of those who have died during or after encounters with the police in France. The parallels with the experiences recorded in Dying for Justice, the recent report from the IRR on deaths in custody in the UK, are telling. While the Collectif is unable in the introduction to give an accurate number of those who have died in police custody, the groups estimate that hundreds have died over the past three decades since 1981 (the abolition of the death penalty in France), averaging around ten deaths a year. A large proportion of the deaths, and the deaths that the Collectif focuses on, are those of young, second-generation Arabs and Africans, often living in the Parisian banlieues.

This book does not claim to be comprehensive, but instead goes into the details of only six cases of deaths during or after encounters with the police; Youssef Khaïf (23), who was shot by a police officer in a suburb of Paris in 1991; Lamine Dieng (25), who died in a police van in Paris in 2007; Abdelhakim Ajimi (22), who was strangled to death in Grasse in 2008; Wissam El-Yamni (30), who died in Clermont-Ferrand in 2012 after a violent encounter with the police that left him in a coma for a week; Amine Bentounsi (29), who was shot in the back by a police officer in Paris in 2012; and finally, Lahoucine Aït Omghar (25), shot five times by a police officer in Montigny-en-Gohelle in 2013.

The title of the book comes from a comment made by the mother of Youssef Khaïf, an activist in Mantes-la-Jolie heavily involved in protests against police violence and the oppression of residents of the banlieues, who died on 9 June 1991 after being shot by a police officer during a chase. On exiting the court ten years later where the officer was acquitted, Khaïf’s mother said that the court had ‘given the police the licence to kill’, and throughout the essays and interviews the idea that ‘the police kill, the justice system acquits’ is reinforced time and time again.

The fight for justice: a familiar story

In all of the struggles described in this book, the recurring one is that for truth and justice after a death. When Khaïf’s mother commented on what she perceived to be the judicial system, the press and politicians working together for the final verdict, the acquittal of the police officers involved, she was echoing a sentiment felt by many families both nationally and internationally. The interviews and pieces written by activists and friends/family members of those killed describe an arduous process, made more difficult by shock and grief: the first hurdle is finding out the circumstances in which the person has died; waiting for the post-mortem to either give credence to or contradict the police officer(s) version of events; the battle with the press, police and politicians over the narrative surrounding the death; and, finally, after families’ and activists’ own investigations to uncover the facts about the cause of death, hindered by police opacity, there is sometimes a trial and appeal.

What is discussed at length, throughout, is the demonisation of those killed by the police and of those who protest after a death. Samir Baaloudj and Nordine Iznasni, from the activist group ‘Mouvement de l’immigration et des banlieues’ (MIB), describe this process: ‘If they are able to discredit the person because they have a history, they will say “he is known to the police force”. Nowadays, when something happens, straight away it is someone from the police federation that speaks.’ How similar that sounds to the shooting of Mark Duggan and the swift, and successful, attempts of the press and police to label him a ‘gangster’, someone who acted violently and was deserving of the violence that he was met with that day.

Such demonisation goes on to cloud the judgement of the court and serve as protection for state and police violence. The presiding judge in the case against the police officer involved in the death of Abdelhakim Ajimi, who died in 2008 in Grasse (after being restrained by several police officers and placed in a chokehold for a prolonged period of time only a few metres from his home) said of the case and Ajimi: ‘The use of legitimate violence is in the hands of the state … if a police officer stops you, you must let them … if Abdelhakim had lived, he would have had to answer for his violence against the police.’ Even after his violent death at the hands of nine police officers, Ajimi is put on trial.

The idea that the police’s use of sometimes deadly violence is legitimate if a person resists arrest in any way, in and of itself perceived as proof of guilt, is widespread. In cases across the world, both the police and the press have exploited this perception of guilt in order to justify police killings. In the case of Jean Charles de Menezes, a Brazilian man who died in London in 2005 after being mistaken for a ‘terrorist’ and shot by the police eight times, misinformation from police quarters immediately justified the killing. De Menezes had worn a suspiciously heavy coat on a hot day, he jumped over ticket barriers running away from police after he allegedly ignored warnings to stop. In South Carolina, Walter Scott was killed on 5 April 2015 after he was stopped and shot eight times in the back by Officer Michael Slager while he was running away. The officer claimed that Scott had fled with his taser, an account that was believed until it was contradicted by witness video footage.

Though the privileging of the word of the police officer in the courts and the press clouds the judgement of the public, activists from the MIB and family campaigns believe that the struggle for the narrative and winning over public opinion is important. Nordine and Samir both state that ‘the second victory is successfully establishing the truth… this is a political victory… You search for the truth, and you must obtain it no matter what.’ While the MIB is generally pessimistic about winning the battle in the courts, it believes that through this struggle to reveal the truth, the pursuit of justice is put into the hands of the affected communities.

Mechanics of the struggle

When asked by the Angles Morts about the support that the MIB is able to provide to families, and how others, particularly within local communities, can help the families in their search for justice, Baaloudj focuses on the financial demands of the legal process. While there is a system of means-tested legal aid in France, it is the families who are assisted financially by the MIB to find a lawyer, who have had the most successes in court. The families themselves cite varying difficulties that they face during their ordeals, from financial problems, to police harassment (often leading to the prosecution of protesters), to a lack of wider support on demonstrations.

Ramata Dieng, the sister of Lamine Dieng (25) who, on 17 June 2007, died of asphyxiation after police officers used a chokehold on him, details the work of the Truth and Justice Committee for Lamine that family and friends set up. Such a committee and that for Abdelhakim Ajimi, too, allow for solidarity across campaigns, for experiences of the police and legal struggles to be exchanged and to learn from past struggles, the French equivalent of the family campaigns in the UK which make up the United Families and Friends Campaign (UFFC).

The parallels in the book with what happens to families in the UK are uncanny – but not surprising. What Ramata and others discuss here is the difficulty of maintaining support from the public and wider communities. While directly after a death, it is easy to mobilise hundreds if not thousands on the streets to show their opposition to the police violence that tears through communities, it is more difficult to sustain the momentum over the months and years. Such frustrations were aired last October at the UFFC annual procession from Trafalgar Square where members of family justice campaigns called for more people to join the UK struggles for justice, outside the Crown Prosecution Service, at court supporting families, and on wider demonstrations. As the editors of the book write, ‘In the face of this impunity that authorises the police to continue to spread their violence, only self-organisation and struggle have at times brought about justice.’

Struggles for justice today

Because the book only describes six cases of deaths in France, albeit in vivid detail, it does not discuss the most contemporary ones. In just over a month, a criminal court in Rennes will announce its verdict in a high-profile case involving two police officers in the deaths of Zyed Benna (17) and Bouna Traoré (15).

On 27 October 2005, Benna, Traoré and Muhittin Altun (17), who had finished playing football and were walking to their homes for iftar (Ramadan meal) in Clichy-sous-Bois, on the outskirts of Paris, were chased by police, and subsequently hid in an electricity substation. Benna and Traoré were killed by tens of thousands of volts of electricity, and Altun survived with severe burns. The police officers are being charged with ‘non-assistance to a person in danger’ and could face up to five years in prison and a €75,000 fine for allegedly failing to come to the boys’ aid and to notify the energy company that they were in the substation.

Throughout, the legal process has been a struggle for the families, who say that they have been unable to grieve and are still seeking the truth and closure. An initial investigation recommended that the police officers face trial, but the state prosecutor appealed this decision on the basis that the police officers had committed no crime; the case was dropped. The families of the two boys fought the decision in higher appeal courts, finally bringing the case to a five-day trial in March this year. In spite of the difficult ten years that the families have waited for the case to be brought to trial, the prosecution requested an acquittal, and the judge remarked to the officers, ‘I salute your courage … you are a testament to how much the Republic would be weakened without its police force.’ Here the words of Farid El-Yamni, the brother of Wissam El-Yamni who was beaten and tear gassed by police officers, thrown unconscious into a police cell, and later died in hospital in 2012, are most pertinent: ‘You promised us your Republic, you promised us values, now it is clear that it was all a farce.’

Related links

Buy the book here

Download an IRR report: Dying for Justice

A toutes les victimes des Etats policiers

Résistons Ensemble contre les violences policières et sécuritaires

Thanks for this book review on what’s happening in France! And for your work on deaths in custudy in Britain. For France, it makes the demonstration after Charlie Hebdo, where thousands scanded “We are the police” even more disgraceful. The US with it’s ongoing process of impunity and militarisation of the police aren’t far away. Luk, Brussels, Belgium