An eyewitness account of the ongoing struggles of the Gilets Noirs in Paris

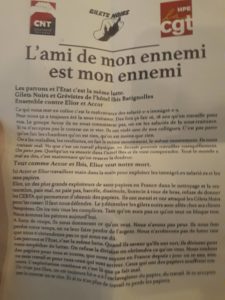

On 19th January, dozens of undocumented migrants filled the lobby of Hotel Ibis Paris Bastille Opera, just outside the centre of Paris, and declared an occupation. They were members of the Gilets Noirs, a collective of sans-papiers (so called ‘undocumented’ migrants, or those without the necessary documents to legally remain and work in France). Their name is a reference to the anti-austerity Gilets Jaunes movement and their actions centre around highlighting the exploitation of migrant workers and demanding immigration papers for all. Among them were around two dozen striking chambermaids—workers at the Hotel Ibis Batignolles in Paris, part of the Ibis chain which is owned by multinational hotel group Accor and which subcontracts its workers to cleaning and catering multinational Elior—as well as a handful of students, and supporters from the chambermaids’ union, the CGT.

‘Papiers et dignité pour toutes!’

‘Papiers et dignité pour toutes!’

Two days previously, the chambermaids of Hotel Ibis Batignolles had marched through the city to mark six months since the beginning of their indefinite strike, a response to being outsourced to Elior which they say is ‘abusive’ as it allows Hotel Ibis to cut costs at the expense of their wages and creates a two-tier workforce. The strike was also a protest against the sexual assault of one of their co-workers by the former hotel manager last year and the denial of the female workforce’s dignity.

The demands of the Hotel Ibis occupiers, announced to occupants of the hotel lobby over a mobile sound system and released as a press statement online, included ending the exploitation of all Hotel Ibis Batignolles workers, reinstating those fired during the strikes, and bringing them all in house. These are not modest demands; but they go further. They are also asking Elior to commit to providing the necessary documents for the workers to obtain ‘papers’ (the documents that denote a legal right to reside and work in France) and to commit to ending its collaboration with sites in which migrants are tortured (detention centres, prisons, police stations, courts). The announcement concluded with chants of ‘Papiers et dignité pour toutes!’ (‘Papers and dignity for everyone!’), which morphed into a brief ‘Pas de policiers!… des papiers!’ (‘Not cops, papers!’) at the arrival of the police. In the impromptu speeches that followed, occupiers expanded on the precarity they experience at the nexus of labour exploitation and border control, explaining that their struggle against bosses and the state is ‘the same struggle’ because ‘both want us to die.’

Throughout the afternoon, members of the Gilets Noirs stressed the neocolonality of their position: the French state imposes controls on their lives in France by denying them papers and driving them into precarious and exploitative labour, while simultaneously imposing itself upon their home countries in Francophone Africa through the arrangement of corrupt governments and harmful trade deals, giving them cause to migrate in the first place. A statement circulated by the Gilets Noirs online after their occupation of the Elior tower in June 2019 identifies other targets as ‘Total and Areva who plunder Africa, Suez which steals its water, Société Générale which steals its money and which finances pollution from Africa with coal-fired power stations, from Thales who built the weapons with which they wage war there.’ As A. Sivanandan’s aphorism goes, ‘We are here because you were there.’

Reproducing and profiting from precarity

According to the French Minister of the Interior, the total number of undocumented migrants in France is around 300,000, but the real number may be much higher: fake, shared, or rented papers are commonly used by those in work (Verso). Outsourcing allows firms to avoid accountability for employing workers who lack the right to work by shifting the blame further up or down the supply chain, while still profiting from the workers’ precarious status by underpaying their labour. As Kanouté, a founder of the Gilets Noirs, told Luke Butterly, ‘Lots of companies go for undocumented migrants over other workers… because they know they can exploit them.’

This exploitation isn’t the only way in which these companies profit from border control. France has one of the most widespread immigration detention regimes in Europe, which migrant rights groups warn will increase following the introduction of a new law raising the maximum detention period from 45 to 90 days. The French state contracts Elior, the same company contracted to employ Hotel Ibis chambermaids, to provide cleaning, catering and laundry to several detention centres. Migrants, who compose the vast majority of Elior’s workforce, are employed to clean the very same detention centres, courts, and airports in which they are detained, judged, and deported, while Elior reaps the profits.

The route to regularisation

The route to regularisation

While the situation is dire for undocumented migrants in France, there is also hope. The relationship between labour struggles and migrant justice struggles is relatively strong; the CGT union claims to have 10,000 undocumented migrants among its membership. Historically, the strike has been one of the most effective means to obtaining secure immigration status in France. In 1980, seventeen Turkish textile workers in Paris, supported by the CFDT union, went on hunger strike over poor working conditions and demanded immigration papers. This turned to mass demonstrations, and eventually resulted in the regularisation of 3,000 workers (W. Pojmann, 2008, p. 82).

More recently, a group of 26 sans-papiers, outsourced to Chronopost, a subsidiary of French postal service La Poste in Paris, have declared victory following a seven-month strike. Taking action against their own precarity and the job’s ‘backbreaking and dangerous conditions’ in June last year, they occupied the Chronopost headquarters until they were evicted, and then set up camp outside the Chronopost Alfortville warehouse, southeast of Paris. Joined by other sans-papiers, they totalled around 150 occupiers. On 2nd January this year, all 26 strikers were given the necessary papers to remain and work legally in France. The struggle of the chambermaids of Hotel Ibis Batignolles meanwhile continues. As one worker Sylvie told French news outlet Reporterre, ‘When there is money in the pocket, there is still courage.’

Related links:

Donate to the CGT strike fund to support the Hotel Ibis chambermaids here.

Follow the Gilets Noirs on Twitter: @Gilets_Noirs

Read ‘I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!’: a guide to the Gilets Noirs here