If Boris Johnson’s government survives, the chaos of the immigration system it plans to impose will lead to untold misery.

During the Tory leadership campaign, Boris Johnson set out his approach to immigration policy: to make it easier for highly skilled migrants to enter, and tougher for those who ‘abuse our hospitality’ – the usual bipartisan ‘good immigrant, bad immigrant’ dichotomy espoused by leaders from Tony Blair on.[1] But in his first appearance in the House of Commons as prime minister, what caught the eye of the media was his signalling of support for an amnesty for undocumented migrants. The expulsion of up to half a million people living and working here for many years, without having committed any criminal offence, was a legal anomaly, he said, in response to a question by MP Rupa Huq, and ‘we need to look at … the economic advantages and disadvantages’ of granting legal status and allowing them to pay taxes. Johnson first expressed support for an amnesty as London mayor, but when he raised it as a minister, he said, Theresa May opposed the idea.[2]

The suggestion provoked predictable ire from anti-migration groups such as Migration Watch. But they have nothing to fear from Johnson. As Karma Hickman explained on the Free Movement blog, and as Johnson himself acknowledged, the Home Office has provided regularisation schemes and rules for decades, to clear asylum backlogs or recognise ties built up over lengthy residence, and the criteria he has most recently set out for an amnesty – fifteen years’ residence and a ‘squeaky clean’ record – are comparatively tough.

As he made clear in his response, Johnson’s concern is not with the human, but the economic cost of undocumented work. Perhaps the unspoken rationale is to signal to employers his intention to retain the large number of (undocumented) migrant workers in the low-pay, low-skill areas of the economy – care, construction, agriculture, food processing, hospitality and catering, at least for long enough to find an alternative low-skilled labour source after Brexit drives out the low-paid, low-skilled EU migrant workers. After all, the National Farmers’ Union (NFU) had already warned of a 20 per cent shortfall in agricultural workers because of existing immigration restrictions, and dire warnings about labour shortages in many other fields have been circulating.

Radical reform?

Johnson’s speech was, of course, mainly about delivering Brexit. But he did say that he intended a ‘radical rewriting’ of the immigration system. This ‘radical rewriting’, though, had nothing in common with the reforms called for by Amnesty International, among others, to repair a ‘broken and inhumane’ immigration system. All Johnson proposed was an ‘Australian-style points system’ awarding points for professional and personal attributes such as experience, earnings, age and qualifications – a system to which the UK’s points-based system for work visas, set up by Labour in 2009, bears a strong resemblance. His scrapping of the May/ Cameron pledge to reduce immigration to the ‘tens of thousands’, confirmed by a spokesman, was probably done not with the intention of increasing immigration levels, but because it was a permanent hostage to fortune, never achieved, a constant reminder of the folly of unfeasible pledges.

Not so much a radical rewrite, then, as a lot of bluster and no real change. And nothing said or done since gives cause for hope. To the boat people crossing the Channel in dinghies, he has said ‘we will send you back’. ‘You are an illegal migrant and I’m afraid the law will treat you as such.’ Never mind that anyone seeking asylum must be treated as a refugee first, unless proved otherwise.

Dream team – or nightmare?

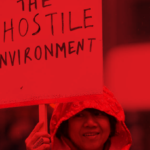

The direction of Johnson’s thinking can be seen most clearly through his appointment of Priti Patel as home secretary. The daughter of immigrants from Uganda who set up a corner shop which developed into a chain of businesses, she was forced to resign as international development minister under Theresa May over secret meetings with senior Israeli politicians about using UK aid to fund Israeli ‘humanitarian’ operations in the occupied Golan Heights. Patel is not human-rights friendly, voting in 2016 to repeal the Human Rights Act and in 2018 against retaining the Charter of Fundamental Rights after Brexit. She also voted against giving asylum seekers the right to work after six months, and in favour of strengthening hostile environment measures by criminalising the provision of housing or banking facilities to undocumented migrants. On her appointment, Patel chose the Mail on Sunday to vow a ‘tough rewrite’ of the immigration system where ‘we decide who comes here based on what they have to offer’, with priority given to ‘brilliant scientists, academics and highly-skilled workers that we want to see more of’.

EU citizens’ rights up in the air

What about everyone else, those who are not brilliant scientists or academics? In particular, and most pressingly, what about all the EU citizens living and working in the UK, and their families? In his 25 July speech, Johnson assured the ‘3.2 million EU nationals now living and working among us’ that ‘under this Government they will have the absolute certainty of the right to live and remain’. But less than a month later, on 19 August, Johnson threw that absolute certainty into confusion by saying that free movement from the EU would end on 31 October in the event of no deal, thereby disowning Theresa May’s pledge that, in the absence of a deal, EU nationals would retain free movement rights until the end of 2020. Although no one has spelled out exactly what Johnson’s announcement means, a spokesperson said that tougher criminality checks would be imposed immediately, although ‘nothing will change for the three million EU nationals already in the UK’.

How can these statements sit together? Only for those of the three million who are ‘squeaky clean’, who stay put and/ or can provide evidence of their pre-Brexit working life here, it seems – and perhaps not even for them. Critics pointed out that those EU nationals living here who have not yet applied under the EU settlement scheme (and fewer than one-third have applied) will face similar difficulties as the Windrush generation did when they try to return to the UK following absence abroad, or when they try to change jobs, access NHS hospital care, benefits or housing.

How can these statements sit together? Only for those of the three million who are ‘squeaky clean’, who stay put and/ or can provide evidence of their pre-Brexit working life here, it seems – and perhaps not even for them. Critics pointed out that those EU nationals living here who have not yet applied under the EU settlement scheme (and fewer than one-third have applied) will face similar difficulties as the Windrush generation did when they try to return to the UK following absence abroad, or when they try to change jobs, access NHS hospital care, benefits or housing.

Already in March, a Joint Human Rights Committee report warned that the Immigration and Social Security Coordination (EU Withdrawal) Bill going through parliament stripped EU citizens in the UK of their rights, including to social security, with no legislative protection in place to guarantee those rights, and nothing has been put in place since then. Meanwhile, law centres and advice bodies have reported that many hundreds, perhaps thousands of EU citizens living in the UK are wrongly being refused universal credit under ‘habitual residence’ benefit rules, and although the vast majority win on appeal, the average 40-week wait is rendering them homeless and destitute.

As for those EU nationals who seek to enter the UK after 31 October, Johnson’s announcement suggests that they will immediately be subject to the same rules as non-EU nationals (although as yet, there is nothing on the Home Office website to indicate whether or not this is the case). This would indicate that, from 1 November, skilled workers from the EU will only be able to come here if they have a job offer from an employer registered with the Home Office, and can speak English, while the entry of unskilled workers will be conditional on its impact on the labour market here. It is not clear how much of the 2018 White Paper, with its treatment of EU nationals as ‘low-risk’ nationalities for the purposes of visits, study and work, will survive.

What is clear is that the workload of the Home Office and of immigration officials will be massively increased from 1 November onwards, with the introduction of visas and immigration checks for EU nationals, the administration of the EU settlement scheme, and the enforcement of EU overstaying. From past experience, it is evident that administrative chaos will ensue.

‘Unfit for purpose’

It has been accepted for over a decade, even by ministers, that the Home Office is ‘unfit for purpose’. When ministers used the phrase, they did not mean that it has failed to regulate migration in accordance with so-called ‘British values’ of fairness and respect for human rights – if this was the test, the Home Office has been unfit for purpose since at least the 1960s, which saw racism institutionalised in legislation through the 1962 and 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Acts. What ministers meant by ‘unfit for purpose’ was lost files, miscommunication, slow and poor decision-making and general inefficiency, resulting in failure to consider foreign offenders for deportation (the 2006 ‘foreign prisoners’ scandal’ that led to home secretary Charles Clarke’s resignation). This inefficiency combined with institutional racism to produce the Windrush and TOIEC (language test) scandals, both exposed in the past year – pensioners branded illegal immigrants, rendered homeless and destitute, sometimes deported, after fifty years’ residence, and as many as 35,000 international students branded cheats and frauds and told to leave the country with no right of appeal.

In fact, of course, the legendary inefficiency of the Home Office is as much a byproduct of institutional racism as is the hostile environment, the exorbitant fees and the ‘culture of disbelief’ permeating official decisions on asylum, family reunion, student visas and residence rights. A lazy contempt for ‘immigrants’ underlies the endemic loss or mislaying of files, the destruction of important evidence, the months, sometimes years-long delays in decision-making in vital areas such as asylum, keeping those affected in a cruel limbo. And it is getting worse. The number of asylum claimants waiting over six months for a decision increased 58 per cent in the past year, to 17,000 in June 2019, while the total number of unresolved immigration and asylum cases has almost doubled in five years to over 100,000. The response of the Home Office to these delays has not been to redouble efforts to improve decision times, but to abandon the six-month target to decide asylum claims. Delays are spreading through the system – now, citizenship applications take over six months to process. Systematic data sharing with HMRC and DWP, trumpeted in the 2018 White Paper as a way of ensuring error-free real-time immigration checks, has been a shambles. So has outsourcing of visa applications to French firm SopraSteria, which has resulted in thousands of complaints from students and medical staff forced to pay hundreds of pounds extra for ‘premium’ document scanning and biometrics services to ensure applications are submitted in time.

In fact, of course, the legendary inefficiency of the Home Office is as much a byproduct of institutional racism as is the hostile environment, the exorbitant fees and the ‘culture of disbelief’ permeating official decisions on asylum, family reunion, student visas and residence rights. A lazy contempt for ‘immigrants’ underlies the endemic loss or mislaying of files, the destruction of important evidence, the months, sometimes years-long delays in decision-making in vital areas such as asylum, keeping those affected in a cruel limbo. And it is getting worse. The number of asylum claimants waiting over six months for a decision increased 58 per cent in the past year, to 17,000 in June 2019, while the total number of unresolved immigration and asylum cases has almost doubled in five years to over 100,000. The response of the Home Office to these delays has not been to redouble efforts to improve decision times, but to abandon the six-month target to decide asylum claims. Delays are spreading through the system – now, citizenship applications take over six months to process. Systematic data sharing with HMRC and DWP, trumpeted in the 2018 White Paper as a way of ensuring error-free real-time immigration checks, has been a shambles. So has outsourcing of visa applications to French firm SopraSteria, which has resulted in thousands of complaints from students and medical staff forced to pay hundreds of pounds extra for ‘premium’ document scanning and biometrics services to ensure applications are submitted in time.

Until recently, EU citizens were largely unaffected by this, with the inevitable exception of eastern Europeans, and in particular Roma, who have borne the brunt of xeno-racist regulation (‘right to reside’ tests for social security, brought in to curb alleged ‘benefit tourism’) and practice (the treatment of rough sleeping as an ‘abuse’ of EU freedom of movement justifying detention and deportation – until ruled unlawful by the High Court).

However, since the Brexit vote, as well as the surge in wrongful refusal of benefits mentioned above, there have been increasing reports of EU nationals receiving letters telling them they have no right to be in the UK and must leave. It is likely to get much, much worse – even in the event of a withdrawal agreement and an orderly Brexit, never mind the nightmare no-deal scenario. It is hard to envisage the extent of the likely chaos and misery around the corner for EU citizens who have lived in the UK for years, but have not made settlement applications or whose applications ‘go astray’ in the Home Office, as they too are treated as ‘only immigrants’.

Related links

Read a Home Office media factsheet on EU citizens and freedom of movement.

I am impressed with this website, rattling I am a fan.