Asylum campaigner John Grayson examines the appalling conditions in privately contracted housing for asylum seekers in south yorkshire.

Ann was showing me round her G4S terraced house, on the inner ring road in Doncaster, on a Sunday afternoon in late October. A few days earlier, Ann had been to the local advice ‘drop-in centre’ for asylum seekers, and told them of her problem with rats in her house. I had received a message from a worker at the drop-in:

‘Am in Doncaster with woman who has rats in her house. She has 6-year-old son who is terrified. She contacted council who came once and put poison. But rats still in oven.’

‘Yes, there was a rat in that oven again on Friday,’ Ann said, ‘My husband took photographs on his phone.’ Mike joined us to show me the picture. ‘There are holes everywhere in the kitchen, at the back door, in the bathroom. We have been trying to stuff things in them for months, then G4S blocked them, but the rats are still here.’

‘Four years ago, when we came here we thought we saw a rat, but it was this year when it started. I came down one morning to look for some shoes for my son David, in the box where we put shoes. His shoes had been eaten at the edges by rats … all the shoes had been eaten. I threw them all away. After that, I saw rats running around my kitchen, and I killed three … maybe four rats this summer. I rang G4S, and told their worker, but they did nothing. I told the council and they came and put poison down.’

The family were from North Africa and Ann and her then baby son had claimed asylum, late in 2011. David was three months old when Ann was put in a mother and baby hostel in Stockton. ‘It was very clean there, but it was too hot and a very small room for us, it was like a prison, so I got out and went back to London.’ I told Ann that I had spoken to women in the hostel around that time and they, just like her, had described their rooms as ‘cells’.

In London, Ann was joined by her husband, Mike, and for eighteen months they tried to survive. ‘We could not pay the rent and had to go to the council. They got us back on support, and we were sent up here to this house in Doncaster. Then last year the police came banging on the window and door, and my husband spent two months in prison for working. Our lawyer is trying to get him support again. Next year David will have been here seven years – that’s our only chance of asylum.’

Ann showed me round the house, clearly in need of urgent repairs – a corner of the living room with damp crumbling plaster, a bathroom with exposed pipes and a damaged bath. ‘I have asked for another house many times. I really do want to move,’ she says.

‘David didn’t speak for many years, now he can’t stop,’ said Ann. David told me ‘I don’t like rats. Yes, I am frightened.’ David showed me his bedroom with a makeshift safety bar across his window. ‘My friend lives there,’ he said, pointing across the back yards, ‘I walk to school with him.’

Ann tells me ‘It’s half-term and David can’t play out the back – the rat holes are by the back door. At the front, there is the road just across from the door.’

The actions taken against the rats did not seem to recognise the fact that a hyperactive six-year-old was living in the house. Normally, a closed rat bait box is used, but G4S also used crude and very unsightly yellow expanding foam to block some of the many rat holes. David was made constantly aware of the rats. David has spent his whole life in the UK asylum system.

I have encountered rats in G4S houses before, In the spring of 2016, a father sent me a video of rats running across the yard where his children should have been playing. In Huddersfield in 2013, I reported rats running round a house for five months with a five-year-old. There were rats running upstairs into a kitchen with a three-year-old child in Sheffield in 2015.

Suzy was pale and ‘looked as if she had not slept well for ages’

Three-year-old Suzy went with her mother, Dorothy, to the Red Cross advice centre in Barnsley. Staff at the advice session were extremely worried about Suzy. One advice worker rang me and said, ‘The child was really pale, with bags under her eyes, she looked as if she had not slept well for ages.’

I went to see the family in their basement flat, down some steep stairs, through the only entrance door. Dorothy and Sam welcomed me and thanked me for coming. They had come from eastern Europe to claim asylum and had been in the flat for three years. Suzy was born in the UK and had lived her whole life in the flat.

The flat felt humid and damp; there was no through ventilation. There was a very small window in the bedroom area which did not give any ventilation or natural light. Sam, Suzy’s father, pointed into the bedroom. ‘We all sleep there in two beds pulled together.’

Dorothy showed me their bathroom. ‘There’s a leak, which never stops, from the bathroom above.’ The bathroom was directly off the main bedroom and had no window. This combination of poor ventilation and leaks was apparent in the peeling ceiling in the bathroom shower.

‘Suzy always has breathing problems,’ Dorothy explains, and shows me Suzy’s medication. ‘We also go to hospital because of Suzy’s hip.’ I see a letter which says Suzy is being treated at the Trauma and Orthopaedics Department at Barnsley Hospital. I remember the steep stairs down into the flat and wonder what will happen to Suzy as she gets older.

Both Dorothy and Sam think the main problem is the constant noise throughout the night from the G4S asylum house above them. ‘There are ten men up there and often thirteen or fourteen with their friends. None of us can sleep, but it is worse for Suzy.’ There is clearly little sound insulation between the flats.

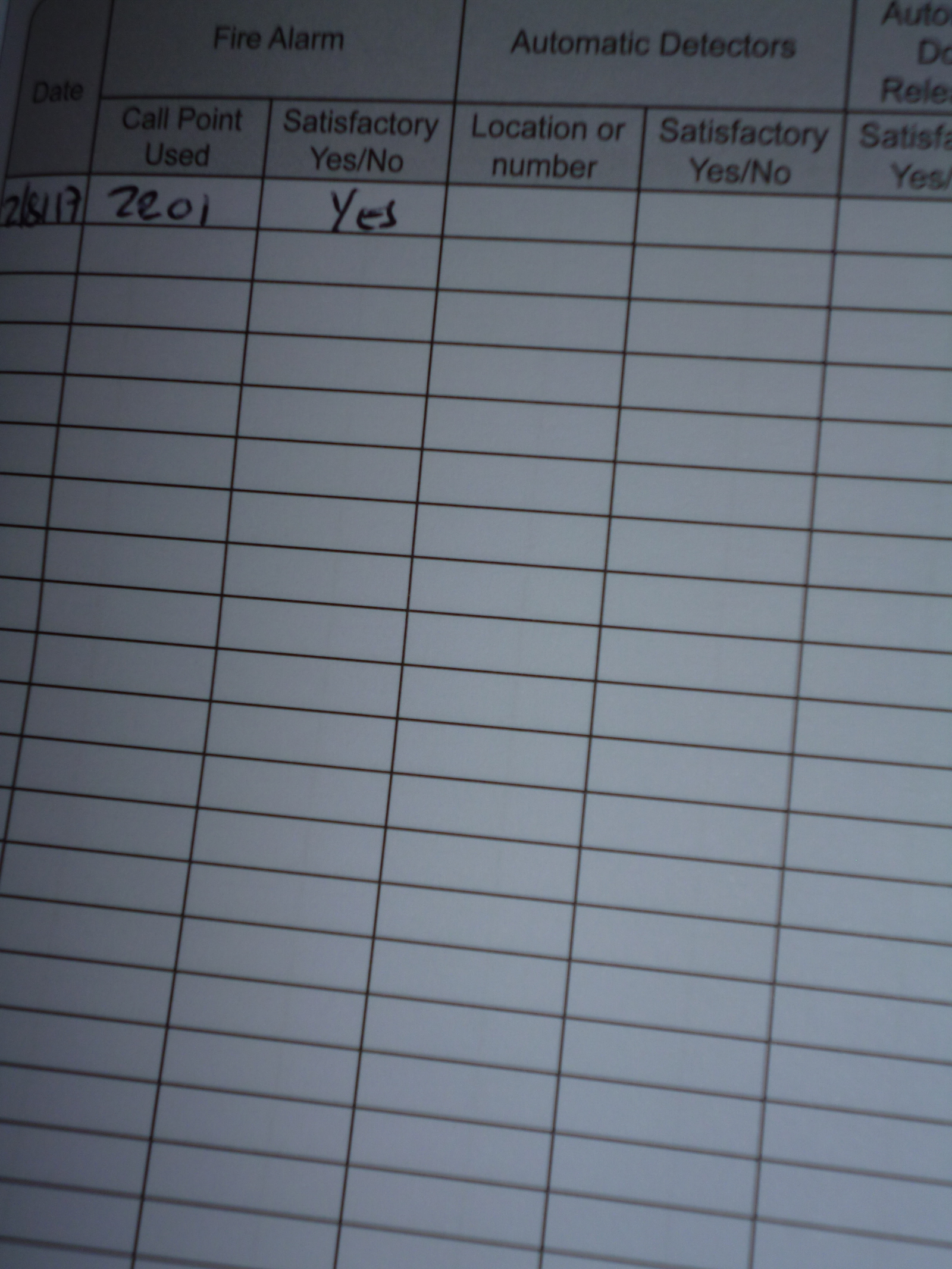

I check the fire safety signs and a fire safety logbook. There are multilingual signs but only one alarm test logged in the book (on 2 August 2017). I did not have time to check thoroughly, but it was clear that the small window in the bedroom was not an adequate escape route.

Both G4S and the Home Office have statutory duties, not only to protect refugee children from discrimination in the asylum process, but also to safeguard them and to ‘promote their welfare’. All the medical and welfare professionals in Suzy’s life have written to the Home Office and G4S. They are unanimous that the family should be moved.

Who will be given asylum housing contracts in the future?

G4S, the largest security company in the world, won a slice of the £1.7 billion UK Home Office COMPASS (Commercial and Operating Managers Procuring Asylum Support) contract in June 2012, with two other security companies, Serco and Reliance, none of them with experience of housing.

On 31 January 2017, the latest UK Home Affairs Select Committee report on Asylum Accommodation found ‘vulnerable people in unsafe accommodation … children living with infestations of mice, rats or bed bugs’. Ten months on from the Inquiry, the Guardian reported on 27 October that asylum seekers were still living in ‘squalid, unsafe slum conditions’.

In December 2016, G4S, Serco and Clearsprings were given a two-year extension to their asylum housing contracts, to September 2019. In August 2017, the Home Office started to advertise for new contracts worth £600 million from 2019. Campaigners will make sure that this time, international security companies like G4S and Serco will not get the contracts to house vulnerable refugee children.

This is an appalling state of affairs. Who is overseeing G4S and the other government funded organisations? Where does responsibility lie for gross maladministration?