A leaked document reveals the government is preparing to withdraw its emergency coronavirus funding for homeless accommodation – a fleeting reprieve that rescued many, whilst those with fewer rights remained destitute. At this juncture, Jessica Perera reviews an important book that interrogates vagrancy as a social crisis that urgently needs addressing.

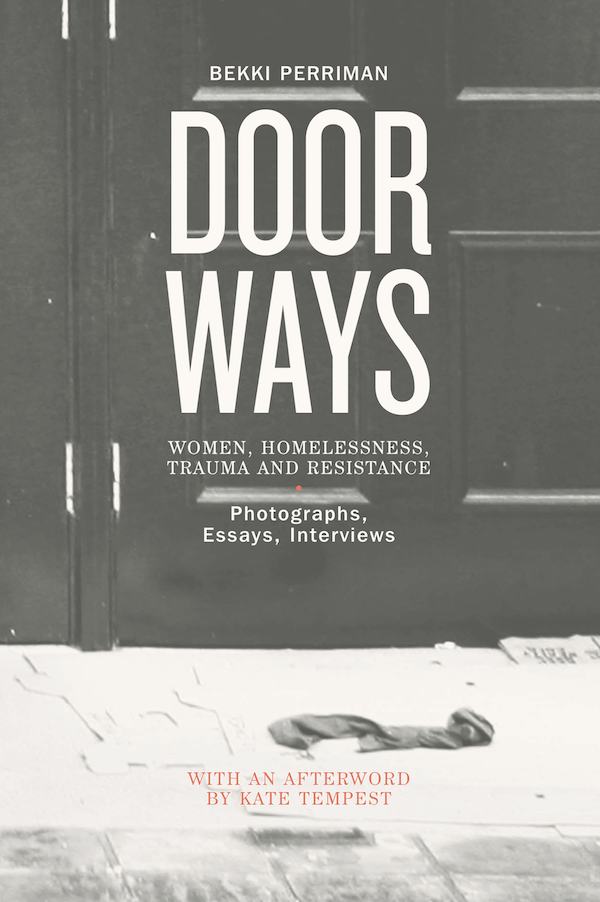

Bekki Perriman’s anthology Doorways: Women, Homelessness, Trauma and Resistance is an extension of a 2014 photography project that captured the crevices where the homeless shelter across Britain. But this is not, as two contributors to the book testify, mere poverty porn to be gobbled up by a cultural capital obsessed city-class elite, which walk past the dispossessed on their way to a gallery. The book has an honest, if not brutal lucidity, because it is born out of Perriman’s lived experience as a destitute young woman; this is art taking a political punch.

The book is comprised of photographs, poetry, interviews, personal histories and ten essays covering a range of topics that delve into vagrancy as it relates to: the neoliberal housing crisis and privatisation; austerity; the lack of adequate support services for women; ‘art’ under capitalism, and more. The interviews are highly affecting accounts which call the reader to listen. As Janna Graham puts it, these are ‘the voices of vanishing people’ who speak, not as participants in an art or research project commissioned under the dictate of capitalist enterprise but, as people with war stories.

Haunting images

Nine images depicting the derelicts doorways preface the collection. For Perriman, these replicate the recessed sleeping spaces she and others would use to provide shelter, warmth and to block out the wind. There is something purposeful that haunts the book. One of the images shows a balustrade guarding an attractive flowerpot; the caption reads ‘I used to sleep here. It was sheltered and tucked away. I’ve noticed they have now put a massive flower pot in this space to keep the homeless out’. Sadly, cities make use of more than just flowerpots. Metal spikes and legal Public Space Protection Orders (PSPO) are just some of the other measures taken by private businesses and public councils to keep the homeless from resting.

Housing crisis

The housing crisis is at the crux of vagrancy, argues urban geographer Andrea Gibbons in her chapter, which puts Thatcher in the firing line for dismantling the post-war consensus around decent, comfortable homes as a right for the working classes. The market forces unleashed in 1979 have ravaged the housing sector, removing all necessary checks and balances to keep people without power, from burning to death or dying on the streets. We can never forget the tragedy of Grenfell Tower, which claimed the lives of seventy-two people and has rightly received much public attention and an official inquiry. Yet, the deaths of 726 homeless people across England and Wales in 2018, has passed without comment. Gibbons argues that ‘to be homeless means to be violently categorised as a thing among other things, a situation instead of a person: a statistic’. She argues that the scale of destitution is so enormous it is becoming easier to ignore, however, it is also indicative that there is something fundamentally wrong with the system.

Decimating local government

A report from the Local Government Association shows that councils have lost £16bn in core funding from central government since 2010, the year the Tory-Lib Dem coalition took power and the year since the number of rough sleepers increased by more than 250 per cent. It beggars belief, that central government during the coronavirus outbreak requested all councils to find emergency accommodation and therefore funding, to house the homeless. Under normal circumstances, London authorities have found that the cost of homelessness prevention and relief, a measure that was introduced under the Homeless Reduction Act 2017, is up to five times higher than the government predicted. But for some this is opportunity! Between 2018 and 2019, in the top fifty homeless black spots in England, private companies providing temporary accommodation to local authorities have amassed profits of more than £215m.

Controlling spaces

The recent 2020 budget suggests that Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak has renewed Thatcher’s war on local government. The spatial justice implications of this assault is elucidated in academic Anna Minton’s chapter which considers how local democracy won in the nineteenth century – the result of widening the franchise – enabled communities to protest against, for example, the gating off of large parts of London. Today, after years of neoliberalism and ‘creeping privatisation’, it is difficult to imagine how people would stage similar battles, given that hundreds of public city spaces and places have been alienated from ‘the people’, through the implementation of Business Improvement Districts, Privately Owned Public Spaces and Secured by Design policies, among others.

The collective agenda of these schemes, Minton tells us, is to keep cities ‘clean and safe’, though this could quite easily be read as banishing vagrants and preventing public protests. Redesigning areas ‘where behaviours and activities are strictly controlled and access is conditional, open only to those who observe the rules’ has created vast defensible spaces. It was, Minton explains, an architect researching crime in New York’s housing projects in the early 1970s that pioneered ‘environmental determinism’ – the theory which posits the physical environment can influence human behaviour. In the 1980s, the theory mutated in Britain as the Secured by Design (SbD) private-public police initiative. SbD standards are placed on all new developments in the UK, including, housing, schools and public buildings and spaces, Minton’s discussion of how this manifests now in the built environment as prison fencing and anti-ram bollards is instructive.

Changing minds

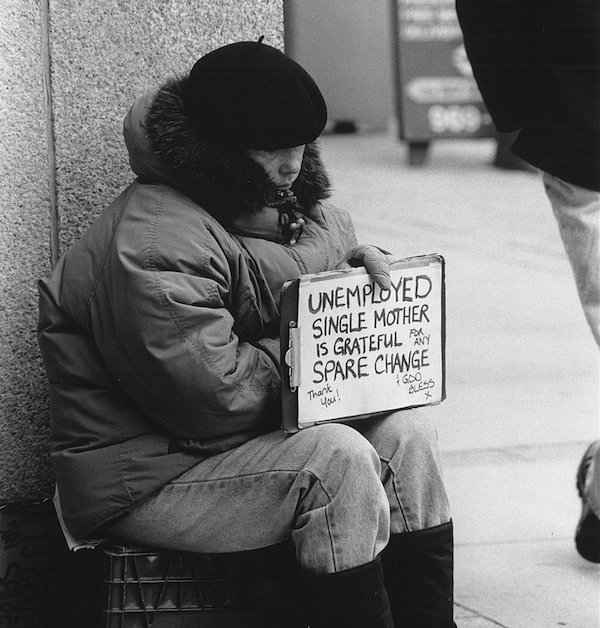

Campaign posters (that use behavioural psychology to ‘nudge’ the public into action) are analysed by artist Mary Paterson as integral to the built environment, influencing how people should spend their money on homeless causes. This is a powerful indictment of advertising among councils and charities, which often ask the public to give to large charity-pots and not to individuals in immediate need. As Paterson argues, the point of such posters are to sever human connections between the public and ‘the roofless’, portrayed as a group of social pariahs out to steal from people’s purses. She positions the moneyed classes as voyeurs who merely observe the penniless and pass judgment on their perceived inhuman identity. But weaves compassion into her polemic, by showing that the roofless adopt the identity of homeless as a form of survival, thus deploying new meaning to downward gazes, dirty fingers and dithering language. ‘Homeless culture’, which draws on common experiences of ‘childhood abuse, war, mental health problems, family breakdown, poverty, unemployment, or a complex combination of these’, engenders solidarity.

Women with complex needs

Services and professionals that cater to women with complex needs are either non-existent or catastrophically failing them, campaigner Lisa Rafferty and psychotherapist Pippa Hockton tell us in separate essays. For Rafferty, the model of the traditional refuge has become obsolete given the increasing demand for intersectional facilities; the scarcity of options are leaving more women destitute or dying in their homes at the hands of abusive partners when they are unable to leave and find alternative accommodation. Hockton draws on casework by Street Talk, a drop-in centre for women involved in street prostitution, to argue that mental health professionals are undiscerning in their evaluations and routinely diagnose conditions such as personality disorder, without explaining the meaning of the diagnosis and how it can be treated. Indeed, this structural violence waged against the poor and precarious is also seen in the reduction to alcohol and drug related treatments across England since 2013/14. As the personal testaments in Doorways reveal austerity is often silent killer, unless you can hear the screams of rough sleepers sheltering in waste bins before they meet their death by crushing.

Race and homelessness

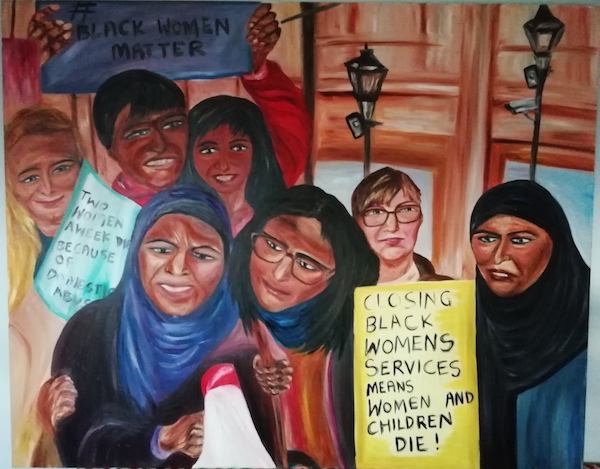

This is an excellent and moving book – with one distinct lack. There is almost no discussion of homelessness or the risk of homelessness, compounding the immigrant and racialised working-class experience. This collection would have significantly benefitted from listening to the voices of those who the Home Office tries to disappear from the streets. In particular, agents have been caught infiltrating ‘immigration surgeries’ set-up in charities – like St Mungo’s – and places of worship to deport homeless immigrants. In general, immigrants and sans papiers are more likely to be made destitute as they are have no recourse to public funds – meaning they are barred from accessing housing benefits due to their unresolved immigration status. And, as John Grayson has shown time and again, refusal to accept appalling overcrowded, unhygienic accommodation that is offered to some asylum seekers and their children, leads to threats of homelessness (as well as risk of contracting covid-19). Yet, private companies such as Serco, callously change the locks of homes for refused asylum seekers. Finally, when reading about the inadequate support services available to women, it is important to recall the specific decimation of refuges catering to the needs of ethnic minority women; with just thirty-four across the UK, the result of austerity.

We are left to imagine the war stories of destitute refugees and the racialised, but, given the often brutal circumstances surrounding their arrival to the UK, it is clear they experience a double baptism of fire.

Interesting, thank you for this perspective.