Why are specialist services for black and minoritised women and girls escaping violence so important? And why have the voices of those organisations been erased from the discussion around Child Sexual Exploitation (CSE) cases in Rotherham and other northern cities? Sophia Siddiqui travelled to Rotherham to find out.

‘For Rotherham’ was scrawled on the ammunition of the gunman who killed at least fifty people in a white supremacist attack at a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand earlier this year. Rotherham as a place has become stigmatised, inescapably yoked to the child sexual abuse scandal that has been used by the far Right (and the mainstream) to fuel anti-Muslim racism.

Three days before the attack, in Rotherham, a number of Pakistani survivors of domestic abuse performed a play. In the opening scene, a 13-year-old schoolgirl sits with her head in her hands as the words ‘Paki’, ‘bomber’, ‘paedophile’, ‘rapist’, ‘terrorist’ are played, ‘all the words that my community can experience on a daily basis’, explains Zlakha Ahmed, founder of Apna Haq, a specialist service for minoritised women and children escaping violence in Rotherham. The play brought home the local impact of a racialised narrative on child sexual exploitation cases, demonstrating how the Pakistani community as a whole has been blamed for the crimes of a few.

‘When you talk to local women, mothers and young girls, they have shared how their 7-year-olds have been called paedophiles and rapists in the playground. Being spat at, stared out, called names or having your headscarf ripped off are things that my community expect to happen, all the time,’ Zlakha told me. But as well as fuelling racism, the toxic racialised narrative around child sexual exploitation (CSE) has erased BAME survivors who don’t fit the white female victim/Asian male offender stereotype. ‘One of the things that I’m forever challenging again is the concept of which children get abused.’ CSE can affect all children – regardless of gender identity, sexuality, ethnicity, faith or economic background – and across various contexts.

Apna Haq: an organisation on the front line

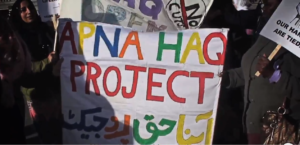

It is in this context that Apna Haq operates. Founded by Zlakha Ahmed, who is herself a survivor of CSE, Apna Haq (which means ‘our rights’ in Urdu) has been working towards the early intervention and prevention of violence against women/girls for the past twenty-five years. Building on the continued legacy of organisations such as Imkaan and Southall Black Sisters, Apna Haq is one of the few BAME specialist services left in the UK. The organisation takes a holistic approach that is both anti-racist and feminist – for women and children who experience racism and sexism simultaneously, one cannot be dealt with without the other.

It is in this context that Apna Haq operates. Founded by Zlakha Ahmed, who is herself a survivor of CSE, Apna Haq (which means ‘our rights’ in Urdu) has been working towards the early intervention and prevention of violence against women/girls for the past twenty-five years. Building on the continued legacy of organisations such as Imkaan and Southall Black Sisters, Apna Haq is one of the few BAME specialist services left in the UK. The organisation takes a holistic approach that is both anti-racist and feminist – for women and children who experience racism and sexism simultaneously, one cannot be dealt with without the other.

As well as offering safety and protection, Apna Haq is committed to raising awareness and challenging the silence around violence against women and girls (VAWG) and challenging racism on the ground. This has involved putting together two three-day courses (now a certificate level diploma to be launched in October), for practitioners who have a very simplistic understanding of the issues, and for communities, in order to challenge the victim-blaming of girls and the excusing of men’s behaviour. ‘Until we have those discussions, we’re not going to change anything.’ These are practical, educational steps that Zlakha is hoping to take out across the country in order to challenge the root causes of violence, rather than simplistic solutions that say ‘these are the signs, look for these signs, report them’ which ultimately lead to carceral ‘solutions’ that don’t change anything.

Compounding oppressions

For racialised women and girls, violence is often experienced at the intersection of state and interpersonal violence. The traumatic experience of domestic violence is further compounded by (eg,) insecure immigration status, poverty, inadequate housing and heavy-handed policing, which make it more difficult to leave an abusive relationship. And the particular vulnerabilities of BAME women (who are more likely to live in a deprived area, in poverty, experience the state care system, and are more likely to experience recurring forms of violence) means that specialist services are absolutely crucial.

Apna Haq has intervened in a range of cases in which victims are faced with social workers, police officers or teachers who take a blanket approach, which does not recognise the complexity of multiple overlapping oppressions. For instance, a social worker that was adamant to immediately inform a 16-year-old’s parents that their daughter was coerced into sex by a boyfriend, without having met the girl or taken care to listen to how her siblings had been forced to marry their partners. A social worker demanding a mother of three move from her home with a leaking roof, without recognising that there was domestic violence in the relationship and her husband had never applied for her immigration stay, which meant that if she moved home she would effectively become an ‘overstayer’. Once Apna Haq supported her through the immigration process, she was able to move home.

‘We’ve had numerous cases where we feel the police have gone into homes in a really, really heavy-handed way, when there are vulnerable children involved’, Zlakha added. In one case, a police officer took a mother and a daughter in for questioning; leaving a 15-year old with severe learning difficulties at home alone until 10.30 at night – this was despite the family being known to the police because of domestic violence call-outs in the past.

Prevent exacerbates stigmatisation

Zlakha also mentioned a case in which a teacher made a Prevent referral resulting in a multi-agency child protection meeting being called after a 13-year-old with learning difficulties described the area she lived in as a ‘terraced house’ and ‘a bridge’, which the teacher misheard as ‘terrorist on a bridge’.

We know the damaging and long-lasting psychological harm that Prevent referrals (which are often made on vague, non-evidence based ‘instincts’) can have on Muslim children who are rendered as ‘criminal’ and ‘suspect’. And for young people who are already caught in a nexus of domestic violence, insecure immigration status and housing, disabilities and mental health issues, the statutory agencies that are supposed to protect them are totally insufficient, and government counter-terrorism policies like Prevent further exacerbate the stigmatisation they already face. It’s in this crisis that specialist services are so essential in order to support vulnerable people to escape domestic violence, but also to navigate through ‘hostile environment’ policies, counter-terrorism policies and austerity measures which make life so difficult, as well as through the racism they face on the streets, on the bus and in their classrooms, which is ultimately the conclusion of a state-sanctioned structure.

Fighting to exist in the face of austerity

Despite the essential work that Apna Haq does, its council funding was cut in 2015, and the tender was awarded instead to a generic organisation, Rotherham Rise. This is part of a bigger trend towards cost-cutting and a ‘one size fits all’ approach in VAWG service contracts, at the expense of specialist services for minoritised women and girls. Since 2012, 50 per cent of shelters in the country for BAME women have been forced to close due to government funding cuts. Only last month, London Black Women’s Project, which has been supporting women and children in Newham for the past thirty-two years, lost its funding for its refuges.

The irony is that despite many specialist service providers receiving little or no local authority funding, statutory agencies continue to rely on these services. Despite losing its state funding, Apna Haq is still fighting to exist through heritage lottery funding and various grants, like so many other specialist services across the country.

Last year, domestic violence homicides reached a 5 year high, and in 2016/7 alone, 13,000 child rapes and tens of thousands of other child sexual offences were recorded (which is likely to be only the tip of the iceberg as studies suggest as little as 3-15 per cent of child sexual abuse is reported). ‘I’m saying, get over the shock because this is reality’, stated Zlakha. We must support these frontline specialist organisations that challenge interlocking systems of oppression on a daily basis and fight to support these vital lifelines.

Related links

Watch a short film ‘Nothing about us without us’ by Dorett Jones which shows the protests that took place in support of Apna Haq in 2015.

The Jajoo award for beygerati goes to apna taarak. Well done