Following a Supreme Court judgment that the joint enterprise doctrine has been applied incorrectly for three decades, Patrick Williams and Becky Clarke reflect on their groundbreaking research on joint enterprise, racism and criminalisation.

Dangerous Associations: Joint enterprise, gangs and racism highlights the complex relationships which contribute to the collective punishment of young Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people to lengthy custodial sentences for offences that they did not commit.  The findings emerge from analysis of a survey of 241 prisoners who were serving Joint Enterprise (JE) sentences and official criminal justice data sources. The study provides a rare insight into a series of interconnected yet concealed criminalising processes driven by a construct of BAME people as being disproportionately involved with gangs and serious violence. This short commentary provides an opportunity to reflect upon the research process and the subsequent public and political response to the report.[1] In particular, we hope to articulate the conceptual barriers and mechanisms that we faced and how such barriers have perennially conspired to both silence and repress the latent racism and discriminatory practices which serve to over-punish increasing numbers of BAME young people throughout England and Wales.

The findings emerge from analysis of a survey of 241 prisoners who were serving Joint Enterprise (JE) sentences and official criminal justice data sources. The study provides a rare insight into a series of interconnected yet concealed criminalising processes driven by a construct of BAME people as being disproportionately involved with gangs and serious violence. This short commentary provides an opportunity to reflect upon the research process and the subsequent public and political response to the report.[1] In particular, we hope to articulate the conceptual barriers and mechanisms that we faced and how such barriers have perennially conspired to both silence and repress the latent racism and discriminatory practices which serve to over-punish increasing numbers of BAME young people throughout England and Wales.

Disproportionality, overrepresentation and ‘strategic silences’ [2]

Racialised disproportionality is an intrinsic feature of the contemporary Criminal Justice System (CJS) of England and Wales. The latest publication of Statistics on Race in the Criminal Justice System illustrates the durability of this fact by again highlighting acute ethnic disparities throughout the ‘system’. Yet, in terms of proposing strategies to reverse ethnic disproportionality, the document offers nothing. The publication simply regurgitates what we have always known. The findings are not an indication of levels of BAME people’s involvement with crime, but are a proxy of criminal justice practice. With reference to the most recent report the reader is informed that ‘no causative links can be drawn from these summary statistics‘. Throughout, the report is positioned as an analytically neutral document, representative of a value-free approach. Whilst replete with complex infographs and running to some 105 pages, the report is implausibly silent on explanation, deftly sidestepping the fundamental question: what are the factors that contribute to the (over)representation of BAME people within the CJS? Such omission of analysis attests to a strategic silence which, concealing processes of criminalisation driven by racist stereotyping, results in the over-policing, conviction and collective punishments of predominantly young Black people.

Approach, Analysis and Categorisation

Dangerous Associations is the result of a collaborative, co-produced study involving support from campaigners, researchers and critical policy analysts. From the outset, the report was conceptualised around a desire to understand anecdotal evidence that the legal doctrine of JE was disproportionately used in cases against young BAME people. This view was also proposed by the House of Commons Justice Committee in 2014, which called for ‘a rigorous consideration of the relationship between the disproportionate application of collective punishments/sanctions and in particular, JE upon BAME individuals and groups’. At its core, Dangerous Associations was set out to illuminate the processes that conspire to associate and (wrongly) convict groups of BAME people for serious violent offences. However, rather than empirically validating the disproportionate use of JE, we wanted to understand the precise policing and prosecution mechanisms, strategies and practices which facilitated this injustice. In terms of method, there was a need to hear the voices of those men, women and children who were serving JE sentences. Added to this, the study necessitated the analysis of official CJ data sources pertaining to the composition of gang databases and the characteristics of those perpetrating serious violence in Manchester and London.

Findings

It has often been said that the omnibus classification of ‘people of colour’ into the singular BAME group conceals particular experiences of state regulation by the penal system. Such an approach assumes a homogeneity which masks the specificity of racialisation. So, whilst our analysis found that the gang discourse was evoked in the prosecution of JE cases for BAME people, further analysis showed that the gang label was particularised to young Black British, Black Caribbean, Black African and dual heritage (Black and White British) men. This finding supports our previous research which demonstrates that police gang databases are in the main populated by Black people.[3] Clearly, for the police and their prosecution teams, the gang is Black.

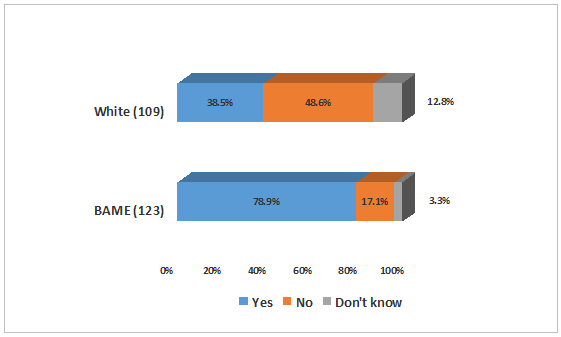

Figure 1: Was the ‘gang’ invoked in the prosecution of your court case?

In Dangerous Associations we unearth evidence that in both Manchester and London, it is non-Black people who are more likely to be convicted for the commission of serious violent offences. Yet, analysis of the survey data found that the Black gang was consistently used as a device to demonstrate common purpose in the prosecution of JE cases. Survey respondents spoke of the use of gang and geographical place names which are synonymous with Black people. For example, ‘St. Anns’ in Nottingham, ‘Gooch’ from the Moss Side area of Manchester, the ‘Burger Bar’ and the ‘Johnson Crew’ from Birmingham were cited within the court arena. We also found that prosecution teams developed elaborate ‘evidence-building’ strategies presenting social media images and text messages of young Black men at parties or on family holidays, where for white JE prisoners there was ‘no evidence’ to support gang involvement. The above was also accompanied by reference to ‘Hip Hop’ music and online ‘rap videos’. Feedback from JE prisoners highlights the appropriation of the imagined violent tendencies of the hyper-masculine Black male reportedly ‘sending soldiers out for revenge’ or ‘protecting turf’. Such dangerous associations invoke the image of the menacing Black ‘other’ parading outside of the normative boundaries of British society and posing a ‘risk’ to members of the public.

Such racist stereotyping serves to convince the jury of common purpose in the prosecution of JE cases involving young Black men. The appropriation by the criminal justice system of the Black gang provides the jury with ‘evidence’ of both foresight and intent. As such, individual culpability becomes collectivised to the secondary parties of the ‘gang’ who are arbitrarily defined by the police as criminally associated with the principal offender.

On 18 February 2016, the Supreme Court ruled that Joint Enterprise has been used incorrectly for the past 30 years. As authors of Dangerous Associations, we welcome this finding. Foresight alone is no longer enough to secure convictions for serious violent offences which carry sentences of life imprisonment. This ruling should now place a requirement on police and prosecution teams to demonstrate and evidence ‘intent’.

On 18 February 2016, the Supreme Court ruled that Joint Enterprise has been used incorrectly for the past 30 years. As authors of Dangerous Associations, we welcome this finding. Foresight alone is no longer enough to secure convictions for serious violent offences which carry sentences of life imprisonment. This ruling should now place a requirement on police and prosecution teams to demonstrate and evidence ‘intent’.

Despite the optimism aroused by the ruling, the racialised gang has consistently been used as a mechanism through which to demonstrate ‘intent’. The Supreme Court ruling should now be used to galvanise a resolve for researchers, campaigners and community activists to disrupt the gangs discourse and the accompanying gangs industry as a means to undermine the use of JE. Firstly, gang databases are shrouded in secrecy. For example, how individuals become registered and deregistered to such databases is still unclear. Added to this, there is little information as to the experiences of policing and/or regulation for those young people who are registered to gang databases. Secondly, there is a need for access to such databases to enable an evaluation of the ‘risks’ that gang registered individuals are purported to pose. Of most importance, there is a need to evaluate the intelligence mechanisms and processes which allocate individuals into ‘gangs’. Within our report, some JE prisoners informed us that they did not know the individuals with whom they were (gang) associated.

- ‘They said we were a drugs gang but I only knew one of my [co-defendants].’

- ‘I didn’t even know the alleged shooter before my arrest. No link to him whatsoever.’

- ‘We knew each other from school and two of my [co-defendants] I’d never met.’

Conclusion

The salient finding to emerge from Dangerous Associations is that many young Black men are serving lengthy custodial sentences not for the commission of violent offences, but for their association to an imagined blackness. Whilst we welcome the Supreme Court’s decision it is essential that we guard against and continue to challenge, resist and disrupt the serious implications that accompany the application of the gang label to young Black people and communities.

RELATED LINKS

Download Dangerous associations: Joint enterprise, gangs and racism, by Patrick Williams and Becky Clarke and published by the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, here (pdf file, 1.67mb)

Joint enterprise Not Guilty by Association (JENGBA)

Centre for Crime and Justice Studies

IRR News: Joint enterprise in action

IRR News: Second joint enterprise inquiry to examine impact on BME communities

IRR News: Joint enterprise, racism and BME communities

IRR News: Joint enterprise: the long and winding road to reform

IRR News: JENGbA welcomes call for reform of joint enterprise