Is the European Court selling Ahmad out, and the kettled demonstrators before him, for the sake of making peace with a British government determined to get the court off its back?

The Strasbourg court’s judgment in Ahmad and others,[1] ruling that the punitive regime in which four of them are likely to spend many years in the supermax prison ADX Florence, Colorado, US, does not prevent their extradition, comes as a bitter disappointment not only to the families and supporters of those involved but to all human rights activists. The conditions were described by a former warder as a ‘clean version of hell’, a sterile, concrete bunker where animal needs (food, clothing, shelter) are met but human needs for communication, activity and contact are scarcely acknowledged. The court heard evidence that inmates have spent over a decade in solitary confinement there (which the European Committee on the Prevention of Torture said should never exceed fourteen days). UN bodies accept that prisoners spending long periods in solitary confinement are deranged and damaged by it. The court’s own previous judgments have acknowledged that prolonged solitary confinement may violate the ban on inhuman and degrading treatment.

The judges, however, ruled that the regime to which the men will be subjected is not inhuman or degrading and will not violate the ban. In doing so, they chose to prefer the government’s optimistic evidence of how the ADX regime worked, to that of the applicants’ witnesses, who described the reality for the prisoners. They ruled that the men’s isolation would be ‘partial’, and that since the US is a country with a ‘long history of respect of democracy, human rights and the rule of law’, prisoners could petition the courts, and could earn more privileges (more recreation and communication) by good behaviour.

These conclusions sit strangely with the acceptance by the court that there may well be prisoners at ADX Florence whose continuous confinement does violate the prohibition on torture or inhuman treatment. The contradictions evident in the judgment give it the appearance of a cobbled-together piece of work – not a bona fide judicial exercise but a cop-out designed to avoid offending either the British or the US government. As the solicitors for four of the applicants pointed out:

‘It will come as a considerable surprise to the inmates of ADX Florence … and their lawyers who struggle fruitlessly to challenge in the US courts their continuing solitary confinement for 8, 10 or 16 years, that the prisoners’ grim isolation could be considered only “relative” and its continuance as justiciable.’[2]

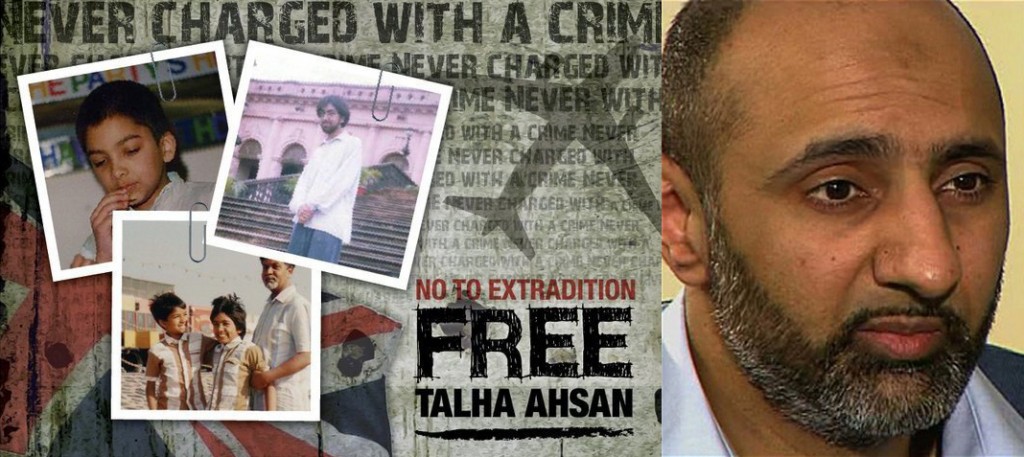

The court simply refused to engage with the alternative to extradition which the men have long called for – their trial in the UK. The judgment, and the proposed extradition, were condemned by the Free Babar Ahmad campaign, while Babar’s sister Nazia told the Independent, ‘My brother has been living in limbo for the last eight years and so have we.’ The younger brother of Talha Ahsan, whose extradition was also upheld in the judgment, said:

‘We shouldn’t let America dominate us unfairly and unjustly – they have been abusive with their power in Guantanamo. The US prison system with 25 per cent of the world’s prisoners and five percent of the world’s population is a disturbing phenomenon in itself.’[3]

Deportation and kettling upheld

On the same day, the court upheld the deportation to Nigeria of a young man convicted of drug-related offences who had been in the UK since the age of three.[4] Moshood Balogun had attempted suicide a number of times following the decision to deport him. The two dissenting judges pointed out that, as a settled migrant who had spent virtually his whole childhood and adult life in the UK, very serious reasons were needed to justify his expulsion. Most of Balogun’s offences had been committed as a minor, and he had no meaningful social, cultural or family ties in Nigeria.

The judgments follow hard on the heels of the similarly disappointing judgment in the ‘kettling’ case, in which the court found that holding demonstrators and passers-by in Oxford Circus with no toilet facilities, food or drink for seven hours without allowing them to leave, was not a deprivation of their liberty.[5]

The rulings come at a time when the British government is seeking to cut down the jurisdiction of the European human rights court in the draft Brighton declaration to be debated by Council of Europe ministers next week.[6] It has repeatedly criticised the court for interfering in its freedom to deport those it wants to deport, and has effectively told the court to concentrate on countries such as Russia and Turkey. David Cameron notoriously called the Strasbourg court a ‘small claims court’ over its upholding of Abu Qatada’s complaint that his trial on torture evidence if deported to Jordan would be illegal as a flagrant denial of justice. It is hard to resist the conclusion that in these judgments the court is seeking to reassure the government that it is listening, and that it is prepared to give the UK authorities its support in deportation and public order cases whenever it can. Not quite the same as giving Gaddafi a present of a dissident illegally rendered from Bangkok – but not a million miles off.