A racialised justice system providing second-class protection to Muslims can be challenged.

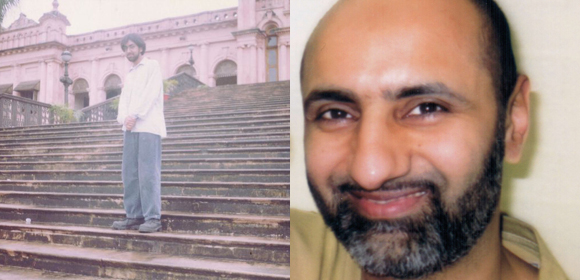

So rare is it to encounter a human, non-racist attitude to Muslims accused of support for terrorism, that a judge’s reasonable and evidence-based approach to the sentencing of Babar Ahmad and Talha Ahsan took everyone by surprise. On 17 July, Connecticut chief judge Janet Hall sentenced Ahmad and Ahsan to twelve and a half and eight years respectively for ‘material support for terrorism’, allowing Ahmad’s release in around a year and Ahsan’s immediate release (although he remains in immigration detention pending his deportation to Britain). These sentences, although striking for their length, were far less than the twenty-five and fifteen sought by prosecutors.

Arun Kundnani and Jeanne Theoharis reported that the judge ‘noted Ahsan and Ahmad’s characteristics of empathy, generosity and wide community of support and accepted that they were motivated not by fanaticism but a desire to end oppression’. She also rejected prosecutors’ assertions of any support for al-Qaida on the website set up by Ahmad, on which Ahsan provided six months of clerical support ending in August 2001. This nuanced approach, recognising the humanity of the defendants and the limits of their culpability, has been largely lacking to date in the judicial, political and media treatment of Muslims caught up in the War on Terror.

The pair’s extradition to the US to stand trial for allegations of conduct in the UK took place with no examination of the evidence,[1] and defied both expert evidence of inhuman conditions for defendants in supermax prisons and a 140,000-strong petition supporting the men’s demand to be tried here. It was emblematic of the second-class justice afforded to British Muslims, who have been extradited when non-Muslims have been spared.

A relatively unreported aspect of the men’s case was the plea bargain which they accepted under enormous pressure. As Richard Haley points out in his analysis for Scotland Against Criminalising Communities, ‘those who refuse a plea deal and are then convicted are likely to receive much harsher treatment than those who agree … for the innocent and the guilty alike, the stakes attached to a not-guilty plea are just too high.’ These pressures mean that just 3 per cent of cases in the US District Courts go to trial. One concern which the House of Lords Select Committee on Extradition Law (currently sitting) should be examining is the use of extradition to subject British Muslims to the US plea-bargain system, bringing this in to our criminal justice system ‘through the back door’.