Radical educationalist Chris Searle examines the response to recent exclusions in the Slovak Roma community in Sheffield in a lecture at the School of Education, University of Birmingham in December 2016.

The conservative restoration continues apace at every level of the British education system, most markedly in our schools. While cuts and austerity policies force local education authorities to become weaker and weaker and more and more comprehensive schools are replaced and consumed by privately-controlled academies and their corporate chains, OFSTED surveillance dominates the working and after work hours of teachers, curriculum development is taken out of their hands, testing and examinations rule supreme from the earliest pupil age, the power of headteacher/managers has never been so extreme and the democratic involvement of teachers and communities has never been so held down and discouraged. Such is the educational landscape nearly three decades after the 1988 Education Act, brought into being by the Thatcher government, yet pursued and institutionalised by successive Tory and Labour administrations.

Yet while such an educational terrain remains the discourse for politicians and academics, life at the very bottom of the education system continues with as much pain and rejection as it has ever generated. There were 3,900 school children permanently excluded from their schools in 2012-13, 4,950 suffered likewise in 2013-14, rising again to 5,800 in 2014-15. These figures do not include those with temporary exclusions or unofficial exclusions who never return to the school system, disaffected and permanent truants or those young people of school age who are working illegally. Yet these ascending figures are the cause of large numbers of school-age children at risk of their own safety on the streets, estates, city centres and shopping malls tempted towards drug addiction, gang activity and violence and petty and serious crime, young people many of whom eventually populate our prison system.

In January 2015 changes were made in guidance with regard to school exclusions, sanctioned by the government, when Minister of State for Education, Nicky Morgan announced that conduct deemed to be ‘detrimental to the education or welfare of others’ is sufficient to have a child excluded from school by the headteacher. The previous threshold required schools to prove that ‘serious harm’ was being caused to fellow students. Thus the option of permanent exclusions being an ultimate sanction, ‘a last resort’ (the expression used for decades about corporal punishment before it was abolished) was removed from the new version of the statutory guidance. Permanent exclusion became an easier expedient for headteachers, particularly as the new guidance removed a further requirement that the student could be permanently excluded without serious or persistent breaches of schools’ behaviour policies.

With the virtual disappearance through austerity, of legal aid for appeals before school governors against exclusion, alongside the lowering of the threshold for exclusion through the new guidance, the school’s advantage in upholding permanent exclusions is powerfully enhanced, and the opportunities of parental success in appeals particularly in struggling neighbourhoods, are greatly diminished. For the main part those who are permanently excluded stay permanently excluded, and rarely find places in mainstream schools again.

A short history of exclusions

The narrative of school exclusion over the past fifty years tells a story of particular communities being disproportionately and systemically affected, especially those communities at the lowest rungs of society, at the bottom of the brazen class system that we were all schooled within. During the sixties, seventies and eighties these were the African Caribbean communities within British inner-cities, and just as it was their youth that were frequently the targets of racist exclusion, so it was their community activists, organisation and street-based scholars who recognised, revealed and exposed the true nature of the damaging effect that this distortion was having on their own sons and daughters.

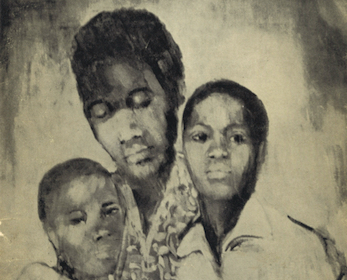

In 1971 the Caribbean Education and Community Workers Association published through the pioneering black community publishing house, the North London based New Beacon Books – an initiative founded by the Trinidadian activist and bookshop proprietor John La Rose – the epochal study by the Grenadian teacher and scholar Bernard Coard, How the West Indian Child is made educationally sub-normal in the British school system.[1] If you want to see an expression of the effect that the truth of Coard’s educational insights was having on an entire community, look at Errol Lloyd’s moving front cover illustration.

In 1971 the Caribbean Education and Community Workers Association published through the pioneering black community publishing house, the North London based New Beacon Books – an initiative founded by the Trinidadian activist and bookshop proprietor John La Rose – the epochal study by the Grenadian teacher and scholar Bernard Coard, How the West Indian Child is made educationally sub-normal in the British school system.[1] If you want to see an expression of the effect that the truth of Coard’s educational insights was having on an entire community, look at Errol Lloyd’s moving front cover illustration.

Coard argued, not from the sheltered confines of a university, but as a black teacher himself in a London school for the so labelled ‘Educational sub-normal’, that there was a grossly disproportionate number of African-Caribbean children being excluded from mainstream education and removed to separate so-called schools for the ‘sub-normal’, in effect exclusion centres where children had none of the educational opportunities of ‘normal’ schools. Coard made five key points which he summarised at the beginning of his treatise. Each point carries powerful now-times relevance and it is entirely applicable to the present situation faced now by other communities at the lowest end of our particularly British class system, and if you substitute ‘children permanently excluded from the British school system’ for the mention of ‘schools for the educationally sub-normal’ his work takes on a powerful contemporary relevance.

‘1. There are very large numbers of our West Indian children in schools for the Educational Sub-normal – which is what ESN means.

2. These children have been wrongly placed there.

3. Once placed in these schools, the vast majority never get out and return to normal schools.

4. They suffer academically and in their job prospects for life because of being put in these schools.

5. The authorities are doing very little to stop this scandal.’

The work of Coard and his fellow activists, scholars and community organisers had a huge influence in raising public consciousness and understanding about the ESN opprobrium and had a direct effect in changing the system during the years that followed.

It also gave other African-Caribbean communities in British cities the inspiration and confidence to tackle the problem of the disproportionate exclusions suffered by their children. In 1985 the Caribbean Times[2] reported that black children across Britain were six times more likely to be excluded from school than their white classmates. The UKAIDI Community Link project in Nottingham revealed a very high level of exclusions of the city’s African-Caribbean children[3]. The Black Parents’ Action Group exposed a similar situation in Reading, as did the Campaign against Racism in Education in Bristol. In the London Borough of Brent, The Parents’ Association for Educational Advance found the same distortion.

In 1984 I was appointed Adviser for Multicultural Education in Sheffield and almost immediately I was faced with the indignation of activists of the Sheffield and District African Caribbean Association (SADACCA) and their belief that disproportionate exclusions affecting their children were happening in Sheffield secondary schools. I persuaded the local education authority (LEA) to organise a survey, and the parents and activists were proved to be correct: there was a distortion. Sheffield Education Department, under the leadership of Bill Walton, a progressive Chief Education Officer who supported a strong anti-racist programme in the city’s’ schools and the Barbados-born Race Equality director, Mike Atkins, created a support team of experienced African Caribbean teachers to bring extra resources into the affected schools to directly help African-Caribbean students. These posts were paid for through Section Eleven of the Local Government Act, whereby the Home Office paid the costs of three extra teachers whose work directly supported black young people, if the LEA was prepared to offer the salary of one teacher. Eventually using this funding method, Sheffield created an entirely new structure, Sheffield Unified Multicultural Education Service (SUMES) comprising 160 new posts, and paid for the training and employment of teams of English as a Second Language teachers, Community Languages teachers of Urdu, Arabic and Bengali, Community Liaison teachers, an educational psychologist and Special Needs teachers, a Translation and Interpretation Service and a curriculum development, library and resources centre with anti-racist resources for all Sheffield schools and teachers. And this was created in the mid-eighties, in the very epicentre of the Thatcher years.

Sheffield: new communities

By the time that the Slovak Roma community arrived and settled in the Page Hall and Darnall neighbourhoods of Sheffield in 2004 when Slovakia became part of the European Union and onwards, these invaluable resources were far gone, depleted and erased by cuts and austerity measures of successive Tory and Labour governments. In Sheffield whole services were lost during the following years from Careers, Community and Youth Services, Educational Welfare posts and Special Needs teams – a whole hinterland of essential services, all of which directly supported and impacted upon disaffected alienated and close- to-the-edge school students, these who were to become the most likely candidates for school exclusion. The Slovak Roma arrivants, quickly settled into low wage, casual and zero-hour employment in factories, fast-food outlets and car-wash enterprises. Their families were frequently housed in unhealthy and slum conditions. Often they became the target of local hostility fuelled by rising xenophobic hysteria, exacerbated during the growth of influence of Ukip and later the crass rhetoric around the campaigning for the EU referendum, which became little more in South Yorkshire than a camouflage barely concealing a plebiscite on immigration. Before and during this process the Sheffield Slovak Roma were the butts of what A. Sivanandan has called ‘xeno-racism’, a form of non-colour-coded racism with a simplistic ideology of ‘our own people first’ and often structured in implacable institutional forms. In her powerfully insightful study A Suitable Enemy[4] the Director of the Institute of Race Relations, Liz Fekete, describes its features in lucid and graphic terms. She quotes Sivanandan’s words which also connect with anti-gypsy racism, one of the oldest forms of the British curse:

By the time that the Slovak Roma community arrived and settled in the Page Hall and Darnall neighbourhoods of Sheffield in 2004 when Slovakia became part of the European Union and onwards, these invaluable resources were far gone, depleted and erased by cuts and austerity measures of successive Tory and Labour governments. In Sheffield whole services were lost during the following years from Careers, Community and Youth Services, Educational Welfare posts and Special Needs teams – a whole hinterland of essential services, all of which directly supported and impacted upon disaffected alienated and close- to-the-edge school students, these who were to become the most likely candidates for school exclusion. The Slovak Roma arrivants, quickly settled into low wage, casual and zero-hour employment in factories, fast-food outlets and car-wash enterprises. Their families were frequently housed in unhealthy and slum conditions. Often they became the target of local hostility fuelled by rising xenophobic hysteria, exacerbated during the growth of influence of Ukip and later the crass rhetoric around the campaigning for the EU referendum, which became little more in South Yorkshire than a camouflage barely concealing a plebiscite on immigration. Before and during this process the Sheffield Slovak Roma were the butts of what A. Sivanandan has called ‘xeno-racism’, a form of non-colour-coded racism with a simplistic ideology of ‘our own people first’ and often structured in implacable institutional forms. In her powerfully insightful study A Suitable Enemy[4] the Director of the Institute of Race Relations, Liz Fekete, describes its features in lucid and graphic terms. She quotes Sivanandan’s words which also connect with anti-gypsy racism, one of the oldest forms of the British curse:

‘It is a racism that is not just directed at those with darker skins from the former colonial territories, but at the newer categories of the displaced, the dispossessed and the uprooted, who are beating at Western Europe’s doors, the Europe that helped to displace them in the first place. It is a racism, that is, that cannot be colour-coded, directed as it is at poor whites as well, and is therefore passed off as xenophobia, a ‘natural’ fear of strangers. But in the way it denigrates and reifies people before segregating and/or expelling them, it is a xenophobia that bears all the marks of the old racism. It is racism in substance, but ‘xeno’ in form. It is a racism that is meted out to impoverished strangers even if they are white. It is xeno-racism.’

This is the racism fostered by the lies and viciousness of politicians and the mass media that surrounded the Brexit vote and provoked an increase of 41 per cent in hate crimes across Britain, with 5,500 racially or religiously aggravated offences in the month after the vote, and the murder of the Polish migrant Arkadiusz Jóźwik in a shopping arcade in Harlow, Essex in August 2016 (the Crown Prosecution Service is not prosecuting the murder as racially motivated). It also affects Sheffield’s Slovak Roma on a daily basis.

The British tabloid press wasted no time in singling out the vulnerable Slovak Roma community in Sheffield for direct attack. Echoing local MP and ex-Blairite Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett’s words that the presence of the Slovak Roma in Page Hall could cause the neighbourhood to ‘explode’ into racial violence, the Daily Star carried its story on its front page in November 2013, with a photograph of Blunkett alongside a headline declaring that ‘Roma migrant Invasion will start UK Riots’[5] The paper’s editorial backed him up:

The British tabloid press wasted no time in singling out the vulnerable Slovak Roma community in Sheffield for direct attack. Echoing local MP and ex-Blairite Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett’s words that the presence of the Slovak Roma in Page Hall could cause the neighbourhood to ‘explode’ into racial violence, the Daily Star carried its story on its front page in November 2013, with a photograph of Blunkett alongside a headline declaring that ‘Roma migrant Invasion will start UK Riots’[5] The paper’s editorial backed him up:

‘David Blunkett is right.

British cities could be hit by rioting because of an influx of Roma Migrants.

Britain has been swamped by immigration in the past two decades.

It’s piled huge pressure on public services like the NHS.

And millions of Brits are out of work as foreigners take cheap jobs here.

We’re at saturation point. Britain is full.

It’s time to close the door.’

As far the young people of the community, Blunkett described them in this way: ‘The Roma youngsters have come from a background even more different culturally because they were living in the edge of woods, not going to school, not used to the norms of everyday life.’ The paper also quoted neighbours claiming that Roma parents ‘will not send their children to school’ and this under another heading attributed to Blunkett on page 4: ‘I predict a riot over UK Roma invasion!’ next to yet another photograph of the ‘loitering’ Roma. (Read an IRR News article: Sheffield’s Roma, David Blunkett and an immoral racist panic)

But what is the true story about the Roma children of school age not being at school? A study of exclusion figures released from the Department for Education describes a very different narrative. They show that in 2015 there were 567 school students in Sheffield schools whose cohort characteristics are described as ‘white Gypsy/Roma’. Of these, in the same year, 148 of these school pupils had been excluded from school, over a quarter of the total school number. When I wrote my book An Exclusive Education[6] which was published in 2001, I sought to document how children from black British and arrivant communities were being unjustly and disproportionately affected by school exclusions. I had no idea that exclusions would ever reach such a grotesque level that now exists against the Slovak Roma community in Sheffield, who live in the very same catchment area of Earl Marshal school where our school in the 1990’s operated a non-permanent exclusion policy. Our policy had the full support of Sheffield’s only black majority governing body, local communities of Pakistanis, Somalis, Yemenis and African Caribbean and even the South Yorkshire Police, whose Chief Constable chose to visit our school to congratulate us for keeping potential excludees in school, and taking in excluded children from other schools, rather than excluding them and setting them loose in the streets to become tempted or compelled into criminal behaviour. When I read the exclusion statistics concerning the mass exclusions of the Slovak Roma children, I had to admit to myself that in fifty years working as teacher, headteacher educationalist and teacher trainer in Canada, Trinidad and Tobago, Mozambique, East London, Grenada, Sheffield and Manchester I had never encountered such outright, blatant and unacknowledged institutional racism in education and it is happening in my home city, Sheffield which has named itself the ‘City of Sanctuary’ and a place of welcome for all arrivant peoples, asylum seekers and refugees from all over the world – except, it seems, if you are a young Roma and you come from Slovakia.

So what has happened to these excluded children; where have they gone? Sent to an LEA exclusion centre, some have been excluded from there. Others have found care and classes at a special ‘inclusion centre’ established by Sheffield’s Yemeni community at their Attercliffe community centre, in the very part of the city where post-war Yemeni migrants worked for three decades in Sheffield’s steel industry. The Yemenis know much about exclusion themselves, and the community have been eager to help the young people of a fellow arrivant community. The young Slovak Roma, over thirty of them, are brought by the Yemeni community minibus from Page Hall to the Attercliffe centre, are given breakfast and lunch, and work at English and Mathematics until the early afternoon, taught by a skilled and dedicated team of teachers and teaching assistants from the Yemeni and Pakistani communities. Attendance is good at the centre, the students speak warmly of its staff and no student has been excluded since its inception two years ago. Even so, the centre has been told that only two of its cohort of students can be considered for re-integration into mainstream school every school year.

I taught English part-time in the centre for a while. Its students wrote about their experiences of exclusion, and I also interviewed them about why they thought they were excluded from mainstream Sheffield schools and what they thought about their present condition and status. Every student that I spoke to was clear in their own mind that their exclusion was the result of their response to racist bullying, baiting and name-calling. These were young arrivant people, in many cases still struggling with using English, yet almost every one of them knew and used the verb ‘provoke’ to describe the causation of their exclusion from school.

‘When I was excluded, this is what happened’, wrote fifteen year old William, ‘I was fighting with other students – Pakistanis and Somalis – because they swore at me. I was proper angry at what they said about my mother. I picked up a chair and threw it’. His classmate George, who has ambitions to become a driving instructor, recounted: ‘Outside the school three Pakistani boys provoked me and threw stones at me. They were swearing at me. They said “fucking go back to your own country” – both white kids and Pakistani kids shouted that to me. So I fought them, I’m not going to let that pass, am I?’

Fifteen year old Sophia told me ‘Some girls at school – English, Pakistani, and Arab – pushed me and swore at me. Even though there are cameras everywhere in that school and every day they were provoking me calling me a smelly Slovak and telling me they didn’t want me in their country, the teachers didn’t stop them. But how can I ignore them? So I had a fight with them. I can’t be friends with them if they don’t want that. One of the boys bruised me in the ear when I had a fight with another girl. He’s still in the school and I’m here!’ She said that she wanted to be a hairdresser and a make-up artist. I asked her if she was getting any careers advice. ‘Yes’ she said. I asked her ‘who from?’ ‘My Mum’ she replied.

One of the most serious and dire consequences of their exclusion is that these children rarely meet and befriend, on a day to day basis, young people from any other community but their own, as they would do if they were still at a mainstream school. This situation is not so different to their segregated experience in Slovakia, where many of them were educated in separate Romany schools. Now they find themselves in a virtual apartheid educational zone in Sheffield, England. 15-year-old Lukas told me that his only friends were ‘my cousins’. Although they live in Sheffield’s most cosmopolitan neighbourhood, school exclusion has meant that their lives have become dangerously ghettoised and restricted solely to companions of their own community.

John is another student who used the word ‘provoking’. He told me: ‘when they call me a “smelly gypsy” and attack me, what am I supposed to do? I have to defend myself don’t I? I’m not going to die. When I was excluded for five days I came back and they provoked me with insults and racism so I fought back again. The only reason that I was fighting was because they hated us and swore at us all the time.’

16-year-old David made similar points: ‘They only wanted to fight, fight, fight and call us “Slovakian bastards”, “gypsy bastards”, “go back to your own country” and all of that. The whole school was on us – English, Pakistanis, blacks, whites. I get emotional when someone calls me those things. The teachers told us, “all right, go back to your classroom, we’ll sort it out” – they told us that every day. But they called us ‘The Slovakian Gang’ and excluded us and kept the ones who attacked us in school. And I don’t like to fight, I like to learn. I want a job.’ He continued with a tear in his eye: ‘You know, I live near the school in Hinde House Lane. Every day in the morning, I looked out the window and saw the ones who provoked us and attacked us going to school in their blue jumpers and uniform, but we were excluded and had to stay at home. I felt how can they go to school, and not me? I didn’t kill no one. I liked the school. I was shocked, I didn’t know that the school and the teachers were so racist. If we are not racist to them, why are they racist to us? If somebody black, white or Pakistani comes to me for help, I help them. I’ve been in Sheffield for eight years, I grown up here, I was six when I came here. It’s not my fault I get angry so easy. My dad just died.’

And finally Anna, aged 14, and with ambitions to become a lawyer, told me her story: ‘The other students were provoking us. They said to us, “you come to England to get the money from us, but you shouldn’t have it” I said, “no, we come here to get a better life.” They said, “this school is not for you. It’s for us, it’s only for the English people”. I know that they all pick on us, the Roma, because we are the newest in Sheffield and when other people come from somewhere else, they will pick on them.’

She told me about her Pakistani friend, Safina: ‘Other kids say to her when she’s with me, that she shouldn’t have Slovak friends, they tried to separate her from me but they never will. She tells the others, “No! She’s my friend and she’s only human like you and me”. They won’t break us up, I know that’.

There are many lessons to be learned from these young people and the grim, anti-social and profoundly retrogressive predicament that they have been placed in. In primary and secondary schools throughout England parents are fined £60 a day for so-called ‘unauthorised absences’ if they take their sons or daughters out of school for an in-term holiday. As I write this, Good Morning Britain has just been discussing the case of parents just returning from Sharm el-Sheikh’s hotels and beaches having to face a hefty fine for their children’s week of absence[7] Yet in Sheffield large numbers Slovak Roma children are not even allowed to step inside a mainstream school, and it is only through the brave efforts of a comrade community that they are receiving any education at all, albeit in a community centre that is just that, with no library, science laboratories, gymnasium, sports pitches, art rooms, few computer facilities or any of the resources that are their right in a mainstream school, and which should be theirs, every school day.

Sheffield community responds

For mainstream schools to permanently exclude children is frequently to do them irreparable harm, particularly in a context when no other mainstream school will accept them through fear of reputation, a perceived damage to examination results or the rumour-mongering amongst some parental groups. Schools need to stand by all their students, giving greater human resources to children, or groups of children, with the most serious and essential needs. The young Yemeni and Pakistani teachers and teaching assistants of the Yemeni inclusion centre who are the real heroes of this story need to be helping the Slovak Roma children in mainstream schools, ensuring their security and success in these schools and acting as a bulwark against exclusion. This should be an absolute priority of these schools. The easy expedient of exclusion harms not only the individual children, but in its wholesale use in Sheffield does damage to families and tarnishes and tortures an entire community. How does a community recover its pride, ambition and momentum when over a quarter of its children are excluded from its local schools?

As for the teachers, conscious and dedicated professionals should never grasp exclusion as an option. An essential principle of comprehensive education is a rejection of exclusion and an embrace of children under particular and seemingly intolerable pressures, such as Slovak Roma children being harassed, bullied, abused and provoked on a daily basis by fellow students. Teaching alienated, estranged and ‘provoked’ children is never easy but is entirely necessary and part of the essential remit of a serious teacher. In his introduction to the pamphlet published by the Institute of Race Relations in 1994, Outcast England: How Schools Exclude Black Children, Sivanandan wrote: ‘Exclusion is seldom the measure of a child’s capacity to learn; it is an indication, instead, of the teacher’s refusal to be challenged.’[8] Challenge is a daily feature of a teacher’s working life: how we measure up to it at every level defines our progress in the profession and our efficacy at fulfilling its tasks.

As for the teachers, conscious and dedicated professionals should never grasp exclusion as an option. An essential principle of comprehensive education is a rejection of exclusion and an embrace of children under particular and seemingly intolerable pressures, such as Slovak Roma children being harassed, bullied, abused and provoked on a daily basis by fellow students. Teaching alienated, estranged and ‘provoked’ children is never easy but is entirely necessary and part of the essential remit of a serious teacher. In his introduction to the pamphlet published by the Institute of Race Relations in 1994, Outcast England: How Schools Exclude Black Children, Sivanandan wrote: ‘Exclusion is seldom the measure of a child’s capacity to learn; it is an indication, instead, of the teacher’s refusal to be challenged.’[8] Challenge is a daily feature of a teacher’s working life: how we measure up to it at every level defines our progress in the profession and our efficacy at fulfilling its tasks.

The example of Sheffield’s Yemeni community and its enthusiasm to help the newest and most abused arrivant community, is a living demonstration of the need for active inner-city communities, who, in a spirit of unity, are determined to help and support each other. While their nation of origin, where most Sheffield Yemenis still retain intimate family links, is being blitzed by British made-bombs dropped by British-made aircraft, where their close families are in daily jeopardy, the Yemenis are providing an education service which the authorities in their own adopted city have virtually abrogated. In a context were the right to attend local schools, to learn, socialise, form friendships and achieve academic success has been taken from them, the young Slovak Roma have learned well that there are also human forces within this foreign city who will loyally stand up for them.

As for the young people themselves, they have learned much in the hardest way, and their experiences of school and non-school have taught them much about survival in the lowest reaches of British society. They recognise that few aspects of life are getting any better, and continue to meet and confront post-Brexit racism on a daily basis. But their stamina and determination are considerable, and not to be easily undermined. As a 22-year-old assistant teacher in a local primary school, Marek Pacan, told a reporter of the Sheffield Telegraph in November 2016 in words signalling hope, consciousness and fortitude: ‘What we have in common is that we are people at the end of the day. The fear of foreign influx is what a lot of people dread. They think “what is it going to be like for my children and grandchildren?” This is why we have had the vote to leave Europe. But what that attitude fails to understand is that this nation has been built on wave upon wave of new people. These new communities bring new energy and new perspectives. As a Roma, I believe I am every-where. I believe I am a hard worker. But we have chosen this place, Sheffield. We are going nowhere.’[9]

Related links

IRR News article: ‘Sheffield’s Roma, David Blunkett and an immoral racist panic‘

IRR News article: ‘The emergence of xeno-racism‘

More valuable perspectives from Chris Searle, thanks.The future looks as bleak as it did in the 80’s and it demands that more individuals ‘stand up to be counted,’ provoke and promote debate and censure through whatever non-violent means possible, primarily the ‘arts’ in its broadest sense and seize every opportunity to identify and join with others.IRR is doing its job by providing the information, the fuel for our action; we need to more effectively co-ordinate it.

Great to see this issue taken up by Morning Star

https://www.morningstaronline.co.uk/a-ff8f-Bullies-Force-Out-Roma-Kids#.WHiqjfCLQdU

and also Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough MP.

Need to keep up the pressure.

Fantastic piece by Chris Searle. These perspectives are so desperately needed.

Just one correction. There is reference to the School Exclusions Guidance 2015 which brought about substantial changes to how pupils could be excluded.

What took place, was that the DfE adopted the new guidance in January 2015 but due to a legal challenge by Just for Kids Law and Communities Empowerment Network, the Education Minister backtracked and reinstated the previous guidance.

Excellent piece detailing the mechanisms of exclusion, which are echoing the systematic segregation of Roma in Czech and Slovak schools (http://www.errc.org/article/slovakia-unlawful-ethnic-segregation-in-schools-is-failing-romani-children/4555).

It would be good if the links to the publications actually connected to these books and reports – clicking on them currently only connects to IRR pages that say the resource cannot be found.

Whilst it’s good to challenge systematic racism, this journal was called Race and Class for a reason. Class discrimination and racism are linked closely. If it’s acceptable for the Conservative government to pursue class discriminatory policies that economically punish the working class, and the so called ‘liberal left’ to pathologically call all white working class people racist, xenophobic and fascist etc ad nauseam, whilst ignoring the growth in economic inequality, journals like this become part of the problem. The ‘liberal’ white middle class in the Anglophone world have become the most wilfully deluded, ignorant and self righteous group of people. Whilst eternally busy calling everyone racist fascist, the PC liberal metropolitan class have become the biggest bigots.