A review on a powerful exhibition at the British Library on the relationship between Britain and the Caribbean post-Windrush, which refuses to take the usual UK-centric approach.

The recent ‘Windrush scandal’ has woken the nation to the institutional cruelty at the heart of the Home Office’s ‘hostile environment policies’. Now, a brilliant free exhibition running until 21 October in the British Library brings it home in a way that can’t be ignored. Celebrating seventy years since the docking of the Empire Windrush in June 1948, this small but comprehensive, nuanced but expansive exhibition provides chapter and verse on the complex British-Caribbean relationship.

From imperial expansion to slavery to the Windrush Scandal

Despite its modest size, ‘Windrush: Songs from a foreign land’ teems with ideas and connections, with a range of fascinating artefacts and audio-video material that captivates the viewer from the outset. In the central foyer of the British Library, you are drawn into the exhibition with Britain’s fifteenth-century imperial expansion, the ‘discovery’ of America and the Caribbean and the imposition of the slave trade. Travelling through time amongst notebooks, posters, plays, papers and even a man’s shirt printed with Caribbean islands, it makes you feel a little like you are walking through someone’s study – these items are important and impressive, but also personal. It ends in the present day with documentary footage of those affected by the ‘Windrush scandal’.

This is not an exhibition that shies from the uncomfortable or difficult. From the first narration board, it spells out just how brutal conditions were in the Caribbean during slavery, as well as after, and that ‘it was popular pressure that ended slavery, meaning freedom has been contested ever since’. More slaves were transported to the Caribbean than anywhere else in the ‘New World’, in large part due to the high morbidity rates on the islands. The money that was made from the sugar plantations has been integral to Britain’s continued affluence. Many British institutions such as Tate & Lyle, Lloyds Bank and even railways were built on money from slavery and the slave trade.

Not the usual UK-centric approach

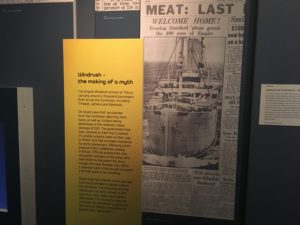

This is no UK-centric exhibition. Key moments in Caribbean history, including independence, are discussed throughout. By telling a much fuller and more in-depth picture of the historical relationship than is usually taught in British schools it refutes the notion that the Windrush generation arrived in Britain as if out of nowhere. Not all Caribbean institutions were supportive of the Windrush generation’s decision to migrate, as shown by clippings from newspapers in Jamaica with one headline reading: ‘Don’t come back’.

It is to be expected that an exhibition on this topic would document the Caribbean contribution to the first and second world wars. But in line with its non UK-centric approach, it foregrounds the Caribbean sensibility, with Harold Moody’s League of Coloured Peoples publication The Keys and C.L.R. James’ The Black Jacobins on display. Less well-known artefacts, such as the 1938 Moyne Report that was suppressed by the British government until 1945, expose the dire living conditions in the Caribbean in part enforced to maintain colonial rule.

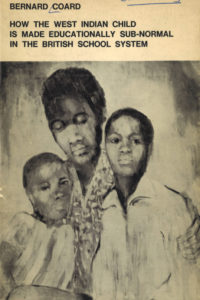

Other items include Bernard Cohen’s pamphlet, How the West Indian Child is made educationally sub-normal in the British school system and Stuart Hall’s 2007 speech which explores how slavery has been remembered and forgotten. By including these items, the curators ask viewers to interrogate their own ways of remembering colonial migration as well as the Caribbean community’s contribution to society.

By highlighting the breadth of Caribbean identities – not just across islands, but across the various ethnic groups – the exhibition refuses to essentialise or homogenise Caribbean communities. Letters written by Indo-Caribbean writer V. S. Naipaul to his brother whilst studying at the University of Oxford describes his feelings of isolation in a Britain that could not accept that someone who looked like him, due to his mixed heritage, was Caribbean.

A female perspective

A number of telling items explore the experience of migration and life in Britain for women. Beryl Gilroy was Britain’s first black head teacher. Her novel, In praise of love and children, though written in 1959 was not published until 1996. In its supporting card, Gilroy explains how she couldn’t get it past the ‘opinionated West Indian males playing the gender game’.

Other items that diverge from the standard Windrush narrative include the pamphlet Marry to Move? which reveals the particular problems some women faced having just married prior to passage. A fascinating glimpse is given of the limits placed on women and just how different society was in the immediate post-war period.

In their own words

In these and many other ways, ‘Windrush: Songs in a strange land’ foregrounds community feeling and activity, whilst never losing sight of British government policy and British media frames. Put simply, it tells the story of the ‘Windrush generation’ in their own words – with poems by James Berry written in ‘invoice’ dialect that won the 1981 poetry prize, a powerful video of Linton Kwesi Johnson performing ‘Inglan is a Bitch’ unaccompanied on the Old Grey Whistle Test, as well as the script of ‘Moon on a Rainbow shawl’ written by Errol John in 1957 to give parts to black actors that were severely lacking.

The exhibition may end with clips from Channel 4’s coverage of summer 2018, but the framing of the whole exhibition illustrates how this is a culmination of the prejudice, discrimination and racism that Caribbean people have always had to contest. On display are North Kensington Police Monitoring Group Rights cards, handed out at Notting Hill Carnival in the early 1980s so that attendees knew their rights around SUS laws. A continuation can be drawn to the use of facial recognition technology used at the carnival last year, showing how little has changed.

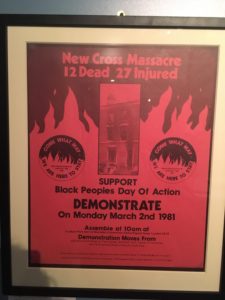

There are also newspapers from the British Defence League, posters for the 1981 National Black People’s Day of Action after the New Cross massacre and, most powerfully, for me at least, a copy of Benjamin Zephaniah’s 1999 poem about the racist killing of Stephen Lawrence. The inquiry into Stephen Lawrence’s death was in the same year as the 50th anniversary Windrush celebrations in 1998.

As well as centring institutional racism and the harsh realities of the Caribbean experience in the UK, the exhibition leaves you with an overwhelming feeling of celebration and pride in the accomplishments made by the British Caribbean communities – despite all that has been, and continues to be, thrown at them.

Related links

Windrush: songs in a strange land

Black Britain and Asian Britain resource at British Library

Race & Class: Catherine Hall, ‘Doing reparatory history: bringing ‘race’ and slavery home’