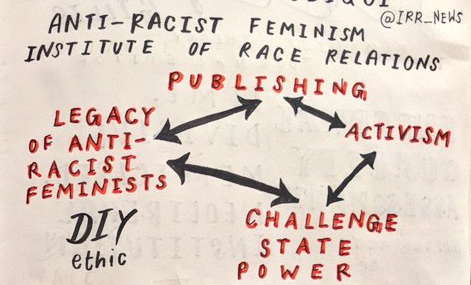

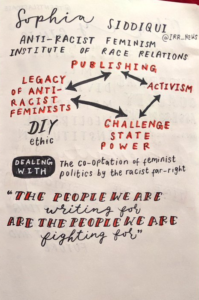

In a republished speech given at a Feminist & Women’s Studies Association event, IRR’s Sophia Siddiqui asks if publishing can be a form of resistance.

It’s clear that our current moment is a moment of crisis – state racism permeates all aspects of life for many communities, the rhetoric of the far Right has become normalised, solidarity can feel tenuous in the face of a neoliberalism that atomises us. But these crisis points are also times of political awakening and an opportunity for social transformation – and publishing has a role to play in this, particularly grassroots self-publishing and DIY cultures, that challenge racism and sexism.

Roots of struggle

One of the most important practices of publishing is to actively engage with histories of anti-racist feminist struggles which have put down strong roots. This does not mean looking at the past in a static way. Seeing the past in relation to the present and understanding how the work we do today builds upon a legacy of feminists before us, can be a source of strength.

Two key books that tell the struggles of working-class black and Asian women in the UK are Finding a Voice by Amrit Wilson (1978) and Heart of the Race by Stella Dadzie, Beverly Bryan and Suzanne Scafe (1985), both originally published by the feminist press Virago and republished in 2018. These two books never set out to be seminal texts; they were written by and for a community – demonstrating how publishing is not just as an individual endeavour but a collective process. The authors’ involvement in OWAAD (the organisation of women of African and Asian descent), and Awaz (the first feminist Asian women’s collective) provided the material conditions for these books to have been written, and the books themselves fed back into activism on the ground.

Publishing and activism were not seen as separate spheres – but they were intrinsically linked. For instance, in Finding a Voice, Amrit Wilson documents the horrific virginity testing that some migrant women were subject to by immigration officers, in the voices of the women themselves. This documentation did not provide evidence in the pages of a book, but it led to direct action – in 1979, OWAAD and Awaz organised a powerful picket protesting virginity testing at Heathrow Airport. Many people don’t know of the horrors of virginity testing, but recalling this history is crucial in order to understand the long legacy of racism that is written into our immigration laws. Women seeking asylum continue to face routine sexual abuse in detention centres like Yarl’s Wood.

No rape, no racism

For publishing to be a form of activism, as well as making historical connections, it must challenge state power, actively seek out justice and resist racialised stereotypes, whilst amplifying grassroots resistance. This isn’t easy. When writing with an anti-racist feminist praxis, you’re treading a contested line – saying that we will not stand for racism and sexism at the same time. But why is this so difficult to maintain? The far Right often racialises sexual violence and co-opts the issue to push a racist agenda, and the mainstream media is central is promoting this toxic narrative – and yet abuse still occurs across communities. In Rotherham following child sexual exploitation cases, this has resulted in Pakistani survivors being erased from the narrative, and the Muslim community being collectively blamed. The impact of this has been daily racism – in 2015, 81-year old grandfather Mushin Ahmed was murdered on his way to the mosque by two men who shouted ‘groomer’ at him.

We must take back the narrative on sexual violence into our own hands through our own words, not by racists who co-opt the issue for their own agenda. This means talking to people on the frontlines who are working to end violence against women and girls and amplifying the voices of survivors. (Read a recent IRR News interview with Zlakha Ahmed who founded Apna Haq, a specialist services for BAME women escaping violence which explores some of these issues).

The co-option of sexual abuse is a narrative that we can see across Europe, as an emboldened far Right continue to make gains on the back of Islamophobia. Now, more than ever, publishing needs to move from the local detail to the transnational – actively creating links to other countries across Europe, as seen in the women’s strikes across Italy, Spain, Poland and the US and beyond earlier this year.

At the heart of feminist activism must be the foregrounding of resistance – women of colour are still and always have been resisting gendered racism and racialised patriarchies. And it’s under the harshest of conditions – in the gig economy, in detention centres, in precarious and exploitative employment – that many struggles are being fought and won. Amplifying these voices is one the most crucial aspects to feminist publishing today, as well as ensuring the language we use is accessible. As the late founder of IRR Sivanandan said, ‘the people we are writing for, are the people we are fighting for’.

DIY cultures

Publishing as activism is not just via the written word. Campaigns led by young people such as ad-hacks on the tube by Education not Exclusion, the creation of zines such as Daikon* (a platform for the south east Asian diapora) and oral history projects such as ‘Fighting sus’ all demonstrate the creative ways new generations are responding to urgent issues today, often by harnessing the power of DIY cultures to explore alternative forms of publishing, outside of capitalist co-option and outside of the academy. The active participation that is integral to DIY cultures brings people together, forming a community. Through events, workshops and discussions, young people are coming together to collectively self-publish their views and make crucial interventions.

By taking a broader view of feminist publishing, and ensuring that it challenges racism, we can build on the struggles of black women, anti-racists and women of colour across the word to work towards a more inclusive feminism, what Nancy Fraser calls ‘a feminism for the 99%’, which stands for all those who are oppressed and exploited in order to transform society as a whole.

Read a review article in Race & Class, ‘Anti-racist feminism: engaging with the past’ (October 2019) that explores these issues further.