A free to download selection of Race & Class articles, compiled by Deputy Editor Sophia Siddiqui, by or about community activists on the black tradition of self-help and mutual aid which enunciates some of the principles now making a come-back as people reclaim self-reliance during the pandemic.

What the Covid-19 pandemic has put into sharp focus is how embedded race and class inequalities place some communities at higher risk of death than others. But we have also seen a welcome upsurge of solidarity in the form of thousands of mutual aid groups springing up across the country, filling urgent needs that have been neglected by a neoliberal, racist state. Groups set up in the community on the basis of mutual aid, not ‘charity’, such as people organising for migrants with no access to public funds, sex workers self-organising a collective hardship fund, groups distributing masks to food-banks, care homes and homeless shelters, all recognise that our strength lies in looking after each other as a way of responding to structural violence.

The principles of self-help in the community – of recognising the importance of caring for each other, not viewing each other as competitors in a capitalist fight but sharing our resources, and maintaining, above all, a commitment to the community outside of the state – has a long history here in the UK, a tradition led by black working-class communities which has been overlooked. The impact of oppressive policing, state neglect, racial violence and poverty wages may be starker during the pandemic, but racialised and working-class communities have been living this reality in the UK for decades, and have often, by necessity, responded with collective resistance.

The principles of self-help in the community – of recognising the importance of caring for each other, not viewing each other as competitors in a capitalist fight but sharing our resources, and maintaining, above all, a commitment to the community outside of the state – has a long history here in the UK, a tradition led by black working-class communities which has been overlooked. The impact of oppressive policing, state neglect, racial violence and poverty wages may be starker during the pandemic, but racialised and working-class communities have been living this reality in the UK for decades, and have often, by necessity, responded with collective resistance.

This free to download Editor’s selection of key Race & Class articles over the last thirty years provides context on this history of self-help community activism, that organised to meet vital needs that were either neglected by a racist state, or engendered by it, whilst also pushing for a more radical ‘normal’.

Self-reliance, self-sufficiency, solidarity

The collection begins with a tribute to ‘Brother’ Herman Edwards, who, after arriving in Britain from Antigua in 1955 as a skilled builder, went on to construct the edifice from which the tradition of self-help in the black community flourished. At a time when ‘racism was raw, stark and unmediated’, Brother Herman saw how alienated black youth perpetually fell into vicious cycles of being forced onto the streets or imprisoned in jail. In Islington in 1969 he set up Harambee, meaning ‘working together’ in Swahili, which provided a range of services for young people including prison visiting, educational programmes, bail hostel accommodation and encouraged young people to gain practical tools to help themselves and each other. The article details Herman’s principled vision of self-help, meaning self-reliance and self-sufficiency, outside of the state: ‘No one expected a racist government to provide; no one wanted a racist social worker or teacher or race professional to intervene’.

Other self-help initiatives in the black community in the 1960s-‘80s included supplementary schools set up across the country, bookshops such as New Beacon, community newspapers including the Black Liberator and Flame, arts centres like Keskidee. One unsung hero of these self-help movements, remembered by Michael Romyn in the next article in the collection, is Jimmy Rogers. Rogers used basketball as a way of engaging disaffected young black children in Liverpool 8 and Brixton, at a time when black young people living in inner-cities were pathologised as ‘criminal’, particularly after the ‘riots’ in 1981.

Jimmy Rogers recognised that a generation of black working-class young people were being left behind. These conditions have continued to worsen in recent years, with the decimation of youth services and the disproportionate number of black students excluded from schools, the impact of which is sure to be exacerbated during the pandemic. Youth workers today are operating remotely and with scarce funds to stay connected to young people during the pandemic.

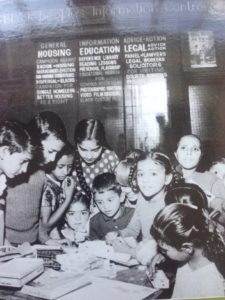

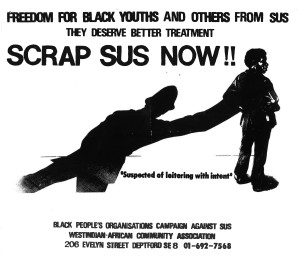

The next piece in the editor’s selection is an interview with long-time campaigner, politician and activist Martha Osamor. The interview documents the community work of United Black Women’s Action Group (UBWAG), which began in Campsbourne estate in north London, through residents getting together and setting up an after school club for children, and developed into several campaigns against the exclusion of black children from schools, the categorisation of young people as ‘educationally sub-normal’, as well as against the SUS laws, which were used to prosecute young black boys before a crime was committed. Although the Greater London Council funded some of these projects later, ‘they started with nothing – from just educating people to be conscious and to do what needed to be done’.

The interview documents the impact of violent policing, from the wounding of Cherry Groce in Brixton in 1981 to the police killing of Mark Duggan in 2011. Today, whilst the state encourages people to report their neighbours to the police for anyone breaching social distancing rules, it’s worth remembering histories and present-day realities of racist policing. Calling the police on young or vulnerable people who may have a reason for being outside is likely to cause harm.

When ‘home’ is not a place of safety

What are the implications of home isolation when children across the country do not have safe homes, and depend on schools and youth clubs, now closed, as a place of sanctuary? Slogans calling for people to ‘stay home, save lives’ overlook the fact that many do not have access to safe homes – people trapped in abusive homes, the incarcerated, the homeless, families given inadequate asylum housing and communities who continue to be dispossessed through gentrification.

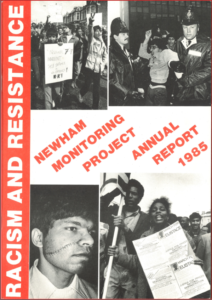

Safe housing is a fundamental necessity for survival. In a republished speech on ‘racial harassment, housing and community action’ by Unmesh Desai on behalf of Newham Monitoring Project in 1987, the author uses cases of racial harassment of the Asian people in their own homes by neighbours in Newham, and the total lack of police or local authority response. It was pressure through grassroots organising that led to the first eviction of a white family who persistently abused their Asian neighbours, rather than rehousing the victims as was common practice at the time. The piece articulates the tensions and contradictions of working with the local authorities, ‘using the tools of the system to fight the system’ – similar challenges facing many mutual aid groups today. As Desai documents, Newham has ‘a long and systematic history of racial terrorism’ directed at the Asian community. Today, Newham’s population is over 70 per cent BAME, with some of the highest rates of child poverty and overcrowding in England along with very poor health outcomes. The borough has been hit the hardest by coronavirus, with the worst mortality rate in England and Wales.

Meaningful solidarity across lines of power

It is clear that the consequences of Covid-19 are not indiscriminate. Low paid members of the workforce – bus drivers, care-home workers, hospital staff, retail and delivery workers – are on the frontlines carrying out essential work, and are more likely to catch the disease as they are more exposed. Low-paid migrants continue to provide essential services for all, often working without adequate PPE, and with no guarantee that their immigration status will be secured after the crisis is over.

Sometimes, they give their lives – on 4 May, we heard of the death of Emanuel Gomes, a cleaner at the Ministry of Justice who continued to work in near-empty offices with Covid-19 symptoms fearing loss of income. In the an important piece by Julie Hearn and Monica Bergos written in 2011, the authors document Latin American cleaners’ fight for survival at the University of London, struggles which continue today, both inside and out of the university, highlighting the importance of solidarity, between cleaners, other workers, students and staff that kept the fight going. It reminds us that mutual aid does not stop at running errands for our neighbours – standing in solidarity with issues of precarity, borders and poverty wages must also be central and part of a deeper process of social transformation that does not end when the pandemic is over.

‘We starved, but we shared’

What happened to the tradition of self-help in the community that flourished in the 1960s-‘80s? In an interview conducted by Kwesi Owusu – the final article in the editor’s collection – leading analyst on black politics and the founding editor of Race & Class A. Sivanandan contextualises the fragmentation of this tradition of self-help. Funding policies meant that groups began fighting on an ethnic basis, in part driven by the state’s multiculturalism policies and the break down of Black unity. In this wide-ranging interview, Sivanandan discloses his own principles of responsibility to one another, instilled in him from growing up in an arid village in Ceylon; ‘we starved, but we shared’. A key principle of the basis of mutual aid is to not viewing each other as competitors, however much the state encourages this, but sharing resources, however scant, between us all.

Featured articles all free to download, from 8 May 2020, for the next month:

- Brother Herman: tribute to a founder of black self help in Britain, vol. 37 no. 3 (1996)

- ‘We could be anything we wanted to be’: remembering Jimmy Rogers by Michael Romyn, vol. 61, no. 2 (2019)

- ‘It has to change’: an interview with Martha Osamor,by Harmit Athwal and Jenny Bourne, vol. 58, no. 1 (2016)

- Racial harassment, housing and community action by Unmesh Desai, vol. 29, no. 2 (1987)

- Latin American cleaners fight for survival: lessons from migrant activism by Julie Hearn and Monica Bergos, vol. 53, no. 1 (2011)

- The struggle for a radical Black political culture: an interview with A . Sivanandan by Kwesi Owusu, vol. 58, no. 1 (2016)

Thank you so much for this timely gift of history and inspiration. It’s good to be reminded that we stand on the shoulders of giants, that we created communities that starved and shared and struggled and celebrated together.