Two creative initiatives – one just finished, the other ongoing – demonstrate the transformative power of the arts in giving voice to the perspectives of marginalised groups.

Little Amal, the 12-foot puppet of the young Syrian refugee, has in The Walk taken the story of refugee journeys across Europe, from south-east Turkey to Manchester, by way of Greece, Italy, France, Switzerland, Germany and Belgium. In the cities and towns she has passed through, from July when she set off from Gaziantep to 3 November, when she arrived in Manchester, she has been greeted by thousands of people, in events coordinated with hundreds of local creative, artistic and refugee groups. She was welcomed by the Pope and by mayors and dignitaries, but mostly by large crowds of local people, some themselves former refugees. Preparations for her welcome have often involved local schools, with children learning songs of welcome, making flowers such as Damascus roses from plastic bags, and sometimes learning to ask questions like ‘Why can’t refugees get on planes and boats? Why do they have to walk?’

The idea for Little Amal, a production of the Good Chance Theatre Company, came from the company’s earlier production The Jungle. In 2015, Good Chance had built its first theatre in the Calais Jungle as a space for residents’ and visitors’ creativity and as respite from the harsh living conditions. The play The Jungle, commissioned by the National Theatre and staged at the Young Vic and then the West End and on to the US, told the stories of some of those stuck there, with actors who had themselves made the journey and had been granted asylum. One of the characters in the play was a young Syrian girl, Amal (whose name means Hope). Thousands of young refugees have made the arduous and frightening journey across Europe, and the company decided to have Amal do it, producer David Lan said, ‘to take the experience of people who are quite brutally marginalised and put it in the centre’, for people to ‘imagine what it would be like to be her’. To make her visible, they made her big: the Handspring Puppet company, makers of the War Horse puppets, made Little Amal, the girl whose Aleppo home was destroyed and who is looking for her mother, who she believes is in Manchester.

Amal was not welcomed everywhere: far-right protesters in Greece pelted the puppet with stones; local councillors in northern Greece refused entry to a monastery village for the ‘Muslim puppet’; and the right-wing mayor of Calais objected to her presence. But hostility was confined to a small minority.

The Walk celebrates resilience, courage, creativity and humanity. It does not purport to be political. But it has become political in the sense that what it is built around – refugees’ odysseys across Europe, and the networks of solidarity that have grown up to support them – have increasingly been criminalised. It is bitterly ironic that in Greece, the coastguards welcoming Amal with a fanfare perform violent pushbacks of refugees into Turkish waters, and those acting in solidarity with refugees, like Seán Binder and Sara Mardini, are prosecuted. Binder and Mardini face trial on 18 November on charges related to their rescue and first-responder activities on Lesvos.

At an Oxford reception, Lan expressed the hope that the 8,000km marathon of street theatre would ‘change the weather’ for refugees in Europe. In its spectacle, the delight it brought to many thousands and the connections it made between artists, refugees, local schools and communities across the continent, such a hope does not seem unrealistic.

‘Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters’

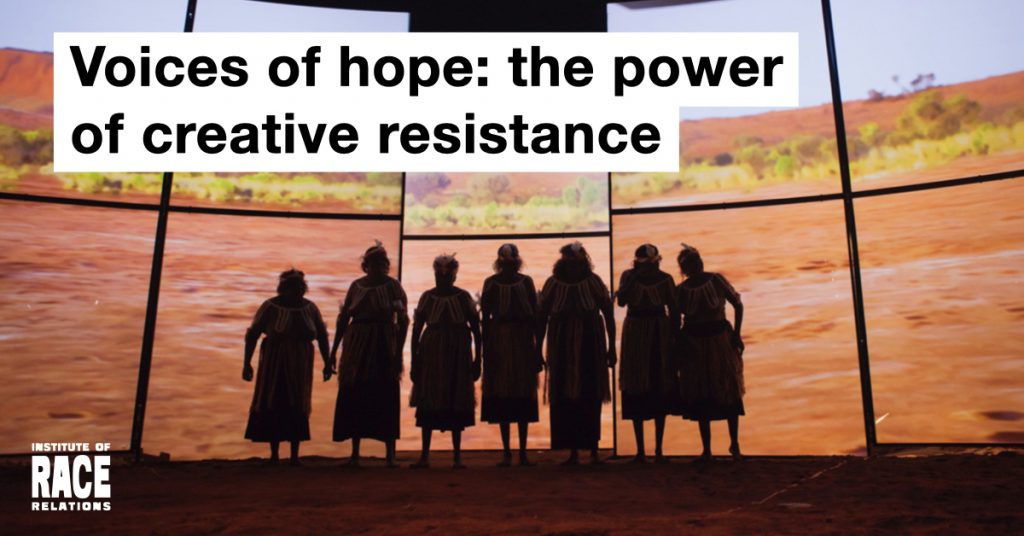

A marathon journey of a different kind is on display at the Box Museum in Plymouth, where Aboriginal artists from Australia are exhibiting their ‘songlines’, in a unique attempt to facilitate a firsthand account of their culture. Through paintings, diagrams and artefacts created in community art centres, supplemented by video enactments of the stories in narrative and dramatic formats, Aboriginal knowledge systems and traditional pre-colonial culture and history are revealed. This contemporary version of knowledge-blending techniques introduces viewers to methods initially created in pre-colonial Australia and used by the then 250 language groups and ‘Countries’. They were simultaneously spiritual, scientific and philosophical thinking systems; methods for creating social moral rules and cohesion; methods of land management, location and geographical guidance; and much more. As one spokesperson for a community arts project explains in the exhibition, We believe that through our paintings, we are creating a bridge, from Anangu people to white people; through the different lines and symbols of our paintings we are making visible to white people our culture and our stories. (Inawinytji Williamson, 1998)

Importantly, this Aboriginal arts movement was and is bound up with ongoing Land Rights campaigning. For example, the establishment of Maruku Arts in 1984 coincided with land rights negotiations with the Northern Territory government. And in recent decades, Songlines ‘have been “translated” and “interpreted” by experts, including historians and anthropologists, for use in land claims under the common law and have been recognised as symbols of land ownership.’[1]

But the main importance of the exhibition is that it allows Aboriginal voices to be heard, unlike most exhibitions relating to Australia, such as the 2018 British Library ‘James Cook: The Voyages’ exhibition which featured no Aboriginal accounts, either of Cook’s legacy or of Aboriginal history and culture.

The exhibition runs until 27 February 2022. As visiting may be difficult for those outside the south-west, much of the exhibition can be accessed via youtube and internet websites. Below are a few suggestions.

Thanks to Danny Reilly for details on the Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters exhibition.

Related Links:

Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters

Songlines Exhibition Virtual Tour

Songlines National Museum of Australia exhibition

Little Amal:

Deserving of supportive comment. Thank you. Provocative arts interventions. ‘Amal’ connects migration with journeys with displacement and the oldest human stories. ‘Songlines’ reconnects with indigenous traditions of ecological responsibility, long displaced by rapacious colonial and capitalist violations.