A new history of the far Right shines a light on the culpability of centre-ground politics for fascist gains.

Britain’s far Right is in pieces. The British National Party (BNP) is electorally dead; the English Defence League (EDL) has been fractured by infighting, its figureheads taking cheap potshots at one another while its leader, Tommy Robinson, is serving a ten-month prison sentence for illegally entering the US. But though down, the Right is not out. In the wake of a successful decade for the UK’s most prominent far-right groups, the anti-immigration, anti-European Union and superficially anti-establishment UK Independence Party (UKIP) finds itself providing an electoral home to the politically destitute of the extreme rightwing.

UKIP, despite no formal association with violent street-level tactics or fascist ideology, reportedly has a shady network of associates (although when such connections are found among its membership, they are swiftly, and publicly, removed): former candidates have had past lives in BNP circles;[1] it has links to an array of nationalist, nativist and homophobic groups in Europe; its candidate for Kent council, Geoffrey Clarke, with the frugality of the eugenicist, recently called for compulsory abortions for unborn children with Down’s syndrome or spina bifida, claiming that without such ‘burdens’ the national deficit could be reduced. It is easy to see how UKIP has found itself capitalising on an extreme Right with no home, and a misanthropic Tory Right, disenchanted by what it sees as coalition compromise and, bizarrely, Prime Minister David Cameron’s ‘social democratic’ tendencies. After a surge in support during which UKIP found itself ‘the third force in electoral politics’, and on the back of predictions that it will steal a significant portion of the Tory vote in the next general election, Tory party vice-chair Michael Fabricant advocated an electoral coalition with them, ceding ground on the question of Britain’s EU membership.

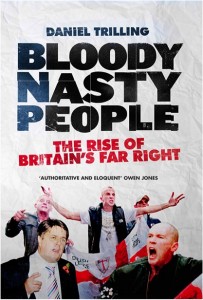

Such a manoeuvre of course is not new. Daniel Trilling’s history of Britain’s far Right, Bloody Nasty People, reveals the parasitic aspects of fascism, its ability to regenerate in new habitats, as well as its capacity to capitalise on those moments of cross fertilisation between the politically extreme and the politically respectable. Drawing on years of experience as a journalist reporting on the far Right for the New Statesman, Trilling draws his readers’ attention to moments when British fascism, despite being at low ebb, found opportunities to regroup and upset the balance at the ballot box.

Trilling, using interviews and archival research, has written a concise and accessible two-part history of the far Right. Part I provides the uninitiated with a solid grounding in the history of fascism in the UK. Trilling recounts the origins of the National Front, which formed from a collection of Nazi sympathisers, charting its rise in the late-1960s (when its policies found credibility in the ‘new racism’ of Enoch Powell), and its fall in the 1980s (after Thatcher had repackaged and absorbed its ideas and made membership to the NF redundant). As factions developed within the NF, its leader John Tyndall founded the modern BNP in 1982, which became the stomping ground for British fascists of every ilk, rising in prominence to the point at which, by the early ‘90s, it had managed to gain a council seat in Millwall, south-east London. But it was later that the BNP was to really unsettle parliamentary politicians, under the leadership of Nick Griffin. Against a backdrop of post-industrial decline, the ‘race’ riots in the summer of 2001 and the war on terror, Griffin set his eye on local government.

Trilling, using interviews and archival research, has written a concise and accessible two-part history of the far Right. Part I provides the uninitiated with a solid grounding in the history of fascism in the UK. Trilling recounts the origins of the National Front, which formed from a collection of Nazi sympathisers, charting its rise in the late-1960s (when its policies found credibility in the ‘new racism’ of Enoch Powell), and its fall in the 1980s (after Thatcher had repackaged and absorbed its ideas and made membership to the NF redundant). As factions developed within the NF, its leader John Tyndall founded the modern BNP in 1982, which became the stomping ground for British fascists of every ilk, rising in prominence to the point at which, by the early ‘90s, it had managed to gain a council seat in Millwall, south-east London. But it was later that the BNP was to really unsettle parliamentary politicians, under the leadership of Nick Griffin. Against a backdrop of post-industrial decline, the ‘race’ riots in the summer of 2001 and the war on terror, Griffin set his eye on local government.

Part I relates a history that is already quite well documented, but by reiterating it, Trilling is able to illuminate the BNP’s rise and electoral gains throughout the 2000s, the focus of the book’s second part. And here he never allows the actions of government and the press to escape his ire. When the BNP won council seats in 2002/03 in the northern towns of Burnley, Calderdale and Blackburn, it pushed debate to the Right. This success was kindled in the embers of the riots that had flared in the region between Asian communities and the police (which had been sparked by the threat of far-right incursion). BNP resentment, according to Trilling, was given credence by a new national narrative, driven by press and government, that Asians were failing to integrate: ‘neither economic deprivation nor white racism was seen to be the root cause; rather it was the deficient culture of an Asian Muslim minority.’

After these successes, New Labour’s response was to try to beat the BNP at its own game. In the months following the riots and in the wake of 9/11, government spokespeople (among them Home Secretary David Blunkett) conflated issues of race with those of immigration, fostering even further the BNP’s thesis that Britain’s whites were being neglected. When the Murdoch-owned national newspaper the Sun joined the fray in August 2003, the war against a ‘horde’ of asylum seekers grew apace with the publication of a series of front-page articles demanding that Labour ‘Halt the asylum tide now’.

Once again, the New Labour government capitulated to the media and the far Right, this time through a policy of triangulation, whereby it adopted the policies of its opponents in a bid to make itself appear above the fray, non-partisan, as though it were putting aside old dogmas for the sake of the national interest. This had helped Labour beat the Tories in 1997 ‘by occupying the space normally held by the right, pushing them further away from the centre.’ Each concession to the Right, however, is met with ever more extreme demands, which in turn enter common political parlance.

One example emerged after the BNP’s 2006 wins in local elections for London’s Barking and Dagenham, which were fought on the myth that asylum seekers were put at the front of the queue for social housing while London’s white poor were left by the wayside. Coupled with the insistence among certain sections of the British media ‘that white working-class people [have] been wronged by multiculturalism’, this became a legitimate topic for debate, pushing the spokesmen of centre-ground government to raise the stakes: ‘What would it mean to “occupy” the space held by fascists? … the [Labour] party should embrace voters’ concerns on immigration and asylum.’ Instead of tackling the argument of the Right and the press and placing the blame squarely on the Thatcher government’s ‘right to buy’ scheme which privatised social housing, Labour accepted ‘the entry of a new character onto the political stage: the white working class’, who were being abandoned as part of a state mantra of multiculturalism, observes the author.

Trilling’s history refutes the dominant version that fascism is somehow cordoned off, simply the domain of separatists who run their groups like rogue states. Rather, he endeavours to trace far-right gains back to the weasel-worded public statements of the mainstream press and ‘respectable’ politicians. Foremost in Trilling’s analysis is a drive to dispel the self-congratulatory half-truth that the British people have always rejected fascism, a stance that lets us off the hook when examining our relationship with the far Right:

In Britain, the far right has often been treated as an aberration, a foreign malady imported into an otherwise tolerant milieu. … [But] by regarding them in isolation, we can also miss what they share in common with the political mainstream, the sources from which their propaganda draws its appeal.

The racist motifs that the far Right embraces, whether they arise as call or response, either initiated by the centre-ground or yielded in response to the Right’s harried demands, are written in the mainstream. They are peddled by the rightwing press, which issues a warrant to shoot the messenger while delivering the message, and by ministers, who condemn the far Right’s demands as they capitulate to its pressure. To understand the racism of the far Right, says Trilling, ‘we must peer into its eyes, even if we risk finding ourselves reflected back’.

Related links

Download an IRR report on far-right violence around Europe: Pedlars of Hate

UKIP expels those found to have extremist connections. The Labour party, on the other hand, welcomes such people – e.g. Maxfield in Darwen, Burke in Milton Keynes.