Jenny Bourne, long time anti-racist campaigner and editor of the IRR’s journal Race & Class, writes about the 1965 Race Relations Act and assesses the fifty years since it was passed.

How should we be evaluating the impact of the race relations acts, the first of which became law fifty years ago?

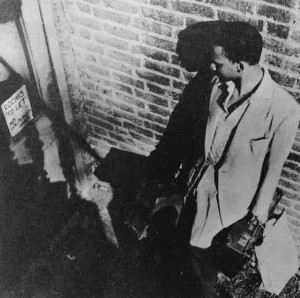

Fifty years ago, on 8 December 1965, race discrimination was outlawed in Britain from clubs and pubs. Fifty years on, black women are mounting a campaign against DSTRKT club for barring their entry on grounds that they are ‘too fat’ and ‘too dark’. So nothing has changed? Plenty has, but for good or ill?

Fifty years ago, on 8 December 1965, race discrimination was outlawed in Britain from clubs and pubs. Fifty years on, black women are mounting a campaign against DSTRKT club for barring their entry on grounds that they are ‘too fat’ and ‘too dark’. So nothing has changed? Plenty has, but for good or ill?

Linking race and immigration

It is fashionable now to insist in political circles that ‘race’ and immigration are not linked. But this was not the case historically. In fact black critics used to argue that every race relations act presaged a new immigration control act. The government of the day could, on the one hand, appear to be non-discriminatory when bringing in immigration controls, by emphasising its willingness to work for the ‘integration’ of those already here, while on the other hand ignoring the fact that those same immigration controls, directed specifically at New Commonwealth immigrants (i.e. ‘darker’ people), were enshrining discrimination in statute.

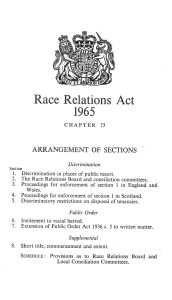

That immigration controls and anti-discrimination legislation were linked in the government mind was quite clearly set out in the announcement on 9 March 1965 by prime minister Harold Wilson. It had three prongs: intensified immigration controls, proposals for central coordination of integrative activities and equal treatment for Commonwealth immigrants once in Britain. The 1965 White Paper on Immigration cut down on the issuing of employment vouchers (established in the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act) and extended checks and controls on dependants. The Race Relations Bill, published subsequently in April 1965 was ‘to prohibit discrimination on racial grounds in places of public resort; to prevent enforcement or imposition on racial grounds of restrictions on the transfer of tenancies; to penalise incitement to racial hatred; and to amend section 5 of the Public Order Act 1936.’

The legislation had been announced in the 1964 Labour manifesto. But party thinking dated back to 1952 when the Commonwealth Sub-committee of the National Executive Committee asked for advice from a former solicitor general and an anthropologist Professor Kenneth Little (author of one of the first books on ‘race’ in Britain). The latter was keen on the type of machinery such as the Fair Employment Practices Commission in the USA. From 1950, private members had pressed for anti-discrimination legislation, and in 1956 radical anti-colonialist Fenner Brockway introduced the first of nine annual Bills. All failed.

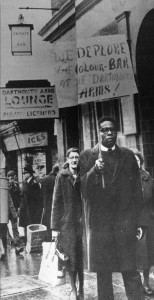

Brockway (later Lord Brockway) himself was influenced by the community-based lobby against what was then termed a ‘colour bar’ in Britain. It was spearheaded by people like Frances Ezzreco who, with Claudia Jones, led a deputation of black organisations after the killing of Kelso Cochrane, to lobby Rab Butler, Conservative home secretary, in 1959 about racism. Claudia Jones, in November 1961, was to write a lead article in the West Indian Gazette denouncing the impending 1962 Immigration Act as a colour bar, i.e. discriminatory, as it would be applied to black people, not white. Prophetic indeed!

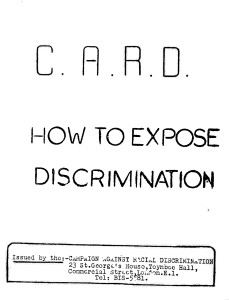

In 1964, when Labour started drafting the Race Relations Bill, incitement was seen as the main subject and stern penalties were suggested as well as making discrimination in public places a criminal offence. Meanwhile a minority group within the Society of Labour Lawyers, led by Anthony Lester, called for civil laws to cover all areas of discrimination, drawing on the US and Canadian experiences. These suggestions were also adopted by the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) the main lobby group. Eventually the 1965 Act, instead of imposing stringent criminal penalties, brought in a Race Relations Board to act as a conciliatory body, without full investigative powers and enforcement powers remaining with the Attorney-General. The scope of the law was not enlarged to cover crucial areas of discrimination in housing and employment. Effectively by restricting the scope of the Act to public places, it gave the green light to discrimination in all other areas.

In 1964, when Labour started drafting the Race Relations Bill, incitement was seen as the main subject and stern penalties were suggested as well as making discrimination in public places a criminal offence. Meanwhile a minority group within the Society of Labour Lawyers, led by Anthony Lester, called for civil laws to cover all areas of discrimination, drawing on the US and Canadian experiences. These suggestions were also adopted by the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) the main lobby group. Eventually the 1965 Act, instead of imposing stringent criminal penalties, brought in a Race Relations Board to act as a conciliatory body, without full investigative powers and enforcement powers remaining with the Attorney-General. The scope of the law was not enlarged to cover crucial areas of discrimination in housing and employment. Effectively by restricting the scope of the Act to public places, it gave the green light to discrimination in all other areas.

Of 309 complaints received between the implementing of the Act and 31 March 1967, only eighty-five actually fell within its scope, the rest relating to employment, housing or financial services.[1] The result was an immediate campaign by the newly-created Race Relations Board and groups like CARD to strengthen the Act and extend its scope. CARD created a Complaints and Testing Committee in 1966 to increase complaints to the Board and used black and white students in a Summer Project to provide proof of discrimination via how a white and a black person were treated at factory gates and in housing provision.

The Race Relations Act was in fact derided by activists, for whom it was a great let-down. Many people like IWA organiser Vishnu Sharma, who had lobbied through CARD, described it as ‘toothless’. Sivanandan in an interview called it not just toothless, but gumless.

Strengthening race legislation

But it was not until 1968 that race legislation changed and this time as a sop to the notoriously racist 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants’ Act which was passed in a record seven days (in March) by a Labour government to prohibit British passport-holding Asians expelled from Kenya (as the country became ‘Africanised’) from coming to the UK on the grounds that they were non-patrial (ie did not have a father or grandfather born here). Which raised the question as to when a British citizen was not a British citizen. Caught in a cleft stick, the government passed the 1968 Race Relations Act extending the scope of the 1965 Act by making it illegal to refuse housing, employment, or public services to a person on the grounds of colour, race, ethnic or national origins and created the Community Relations Commission (CRC) to promote ‘harmonious community relations’. Note that it was the second reading of the 1968 Bill on 23 April, that occasioned Powell to make his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in which he cited a constituent who worried that ‘the black man’ would now ‘have the whip hand over the white man’. (Read an IRR News article: The beatification of Enoch Powell.)

But it was not until 1968 that race legislation changed and this time as a sop to the notoriously racist 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants’ Act which was passed in a record seven days (in March) by a Labour government to prohibit British passport-holding Asians expelled from Kenya (as the country became ‘Africanised’) from coming to the UK on the grounds that they were non-patrial (ie did not have a father or grandfather born here). Which raised the question as to when a British citizen was not a British citizen. Caught in a cleft stick, the government passed the 1968 Race Relations Act extending the scope of the 1965 Act by making it illegal to refuse housing, employment, or public services to a person on the grounds of colour, race, ethnic or national origins and created the Community Relations Commission (CRC) to promote ‘harmonious community relations’. Note that it was the second reading of the 1968 Bill on 23 April, that occasioned Powell to make his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in which he cited a constituent who worried that ‘the black man’ would now ‘have the whip hand over the white man’. (Read an IRR News article: The beatification of Enoch Powell.)

Sections of the Labour Party and their affiliates, including black organisations, had lobbied for extending race legislation, but, with the passing of what became termed the Kenyan Asian Act, many anti-racists despaired of Labour. And in the years to come, pressure to strengthen anti-discrimination legislation was by and large to come from within the quasi-governmental set-up of the CRC and Race Relations Board. The Act brought in in 1976 outlawed indirect (as well as direct) discrimination, and combined the functions of the Board and CRC into one Commission for Racial Equality (CRE). And the 2000 Amendment Act (brought in as a result of the Macpherson Report which found institutional racism in the police) extended the outlawing of race discrimination to public authorities, till then excluded from the scope of anti-discrimination laws, and placed on them a general duty to promote race equality.

The downward path

That was indeed the heyday of legislation and its enforcement, especially when Herman Ouseley was chair and chief executive of the CRE from 1993 to 2000. He told IRR News: ‘During my stint at the CRE, we were not afraid to use the 1976 Act in a very elastic way to support individuals in the Tribunals and courts, to challenge employers and public bodies, to undertake formal investigations fearlessly into bodies such as the MoD and generate support to fund public awareness advertising campaigns focused on the effects of racism.’

The big shift came around 2004/5 with Blair’s new-found enthusiasm for ‘light touch regulation’. By then, Ouseley says, the government felt ‘that they had discharged their responsibilities for implementing the measures arising from the Macpherson report into the killing of Stephen Lawrence’ and wanted ‘to demolish the CRE and absorb it into the Equality and Human Rights Commission … a symbolic edifice for equalities’ high-level blue-sky waffling’.

Now that one organisation is there to act (or not, its budget fell from £70 million in 2009/10 to £17 million in 2014/15) over a whole host of discriminations – age, disability, gender, gender realignment, sexual orientation, religion and race – the specificity of each is lost in the general and the fight against racism undermined. According to Lord Ouseley, ‘there is no relationship with local BME communities or support for individuals’. What support there is consists of a helpline (which does not provide legal advice) subcontracted by the EHRC to the Equality Advisory Support Service which is itself run by the private company Sitel, a telemarketing and outsourcing business headquartered in Nashville. (Fairness is now a global commodity.)

Now that one organisation is there to act (or not, its budget fell from £70 million in 2009/10 to £17 million in 2014/15) over a whole host of discriminations – age, disability, gender, gender realignment, sexual orientation, religion and race – the specificity of each is lost in the general and the fight against racism undermined. According to Lord Ouseley, ‘there is no relationship with local BME communities or support for individuals’. What support there is consists of a helpline (which does not provide legal advice) subcontracted by the EHRC to the Equality Advisory Support Service which is itself run by the private company Sitel, a telemarketing and outsourcing business headquartered in Nashville. (Fairness is now a global commodity.)

Ouseley describes ‘the deathbed Equality Act of 2010’ as ‘a Labour legacy of lost opportunities, light touch regulatory activity and a deficient framework for tackling discrimination across all the equality characteristics’. It provided, he feels, the basis for the Coalition and present governments to do what they like, without challenge, rolling back the gains made in tackling discrimination in the workplace. ‘Employees now find it almost impossible to challenge discriminatory behaviour by an employer through the Tribunal process without attrition and desperation, unless they have a lot of money and time to fight for justice or are not afraid to be bankrupted in pursuit of justice!’ The fees imposed by the coalition government to bring a Tribunal case are well over a thousand pounds – £250 when submitting a form and £950 for a hearing.

Changing the climate

But as Sivanandan had pointed out anti-discrimination laws were not so much ‘to chastise the wicked or to effect justice for the blacks’ as to change public attitudes and thus pave the way to ‘integration’. The 1968 Act, he wrote, ‘was not act but attitude’.[2] In that sense of attitude, the defeat of a strong race body and lobby by 2010 allowed for the establishment’s turn away from multiculturalism. And the defanging of the CRE took place on the watch of Trevor Phillips, head of the organisation from 2003. His position was perhaps summed up in his controversial 2005 ‘sleepwalking into segregation’ speech in which he seemed to place much of the blame on some BME communities for their self-segregation, rather than institutions for their discriminatory practices. The mood music had changed, providing prime minister Cameron the opportunity in 2011, during a speech on security in Munich, to publicly attack ‘the doctrine of state multiculturalism’ and stress the need for ‘British values’. It may not have had the crudity of the ‘black whip hand over the white man’ but it smacked nonetheless of the cultural whip hand.

But as Sivanandan had pointed out anti-discrimination laws were not so much ‘to chastise the wicked or to effect justice for the blacks’ as to change public attitudes and thus pave the way to ‘integration’. The 1968 Act, he wrote, ‘was not act but attitude’.[2] In that sense of attitude, the defeat of a strong race body and lobby by 2010 allowed for the establishment’s turn away from multiculturalism. And the defanging of the CRE took place on the watch of Trevor Phillips, head of the organisation from 2003. His position was perhaps summed up in his controversial 2005 ‘sleepwalking into segregation’ speech in which he seemed to place much of the blame on some BME communities for their self-segregation, rather than institutions for their discriminatory practices. The mood music had changed, providing prime minister Cameron the opportunity in 2011, during a speech on security in Munich, to publicly attack ‘the doctrine of state multiculturalism’ and stress the need for ‘British values’. It may not have had the crudity of the ‘black whip hand over the white man’ but it smacked nonetheless of the cultural whip hand.

The changed cultural whip hand, and of course the unchanging obsession with appearance in the seeking after profit are arguably exactly why a chic London nightclub might, as of nature in 2015, pick and choose its clientele.

Where are we then after those fifty years since the first Race Relations Act? Without doubt the educative function of race laws has worked: generally speaking the threshold of what is tolerable in a liberal society has risen. But at the same time, and as liberal society gives way to market values, there is an insidious creep of the idea that we are now in a post-racial world. There is a largely unspoken view from politicians and opinion-formers that we have done our bit, in fact we may have gone too far in allowing them their rights. Now their demands risk changing society as we want to see it.

Meanwhile and make no mistake about this, in areas where racism and poverty intersect, discrimination is still palpable. In March 2015, while 5 per cent of white working-age people were unemployed; 13 per cent of black working-age people, 9 per cent of Asian and 10 per cent of those from other ethnic backgrounds were unemployed.[3] In March 2015, the proportion of 16-24 year olds from BAME communities unemployed for over a year had increased by almost 50 per cent since the Coalition government was formed. For their white counterparts, there had been a decrease of 2 per cent.[4] In 2015 the ethnic group least likely to be paid below the minimum wage was white males (15.7 per cent); and that which was most likely was Bangladeshi males (57.2 per cent). 38.7 per cent of Pakistani males were paid below the minimum wage, 37 per cent of Pakistani women, and 36.5 per cent of Bangladeshi women.[5] On 30 June 2013, 26 per cent of the prison population was from a minority ethnic group, though they comprise around 14 per cent of the general population. Muslim prisoners accounted for 13.4 per cent of the prison population while they represented 4.2 per cent in the 2011 Census. There are proportionately many more young BAME male prisoners than older ones, with BAME representation in the 15-17 age group the highest at 43.7 per cent.[6]

Cameron’s recent answer to such deep inequality is name-blind application forms!

The fight for racial justice that the Claudia Joneses, Frances Ezzrecos and Vishnu Sharmas began some sixty years back, goes on – and now in a context where the dominant discourse makes it that much harder to argue for equality, justice and an acceptance of difference. Back to the future.

Excellent retrospective piece. One question – did CARD, as an organisation actually place a role in the passage of the 1965 Race Relations Act?

CARD was a lobby group demanding anti-discrimination legislation in Britain. But its particular proposals (drafted by the Society of Labour Lawyers, Anthony Lester [now Lord Lester]being an original member of CARD) were ignored by the Labour Government which amended and weakened the Bill at Committee Stage – no criminal penalties etc. CARD would have had no power in terms of the actual passing of the law in parliament. In fact CARD was composed of people, groups and parties which had differing and often contradictory ideas about what CARD should do . There were strains between those who wanted it to be just a lobby group (akin to the Civil Rights Movement of the US) and those that wanted it to be a national organisation representing New Commonwealth Immigrants. There were strains between those who wanted it to be a Black organisation and the role that white liberals, especially Labour Party people, were obviously playing. There were strains between those who had a mainstream and those who had a revolutionary political programme. Ultimately there were differences as to whether CARD members should work with or against government ‘race’ structures, then in their infancy.

https://www.change.org/p/human-rights-campaign-jamie-button-the-general-chiropractic-council-gcc-s-registration-manager-must-resign-now-20061adc-6e28-4b48-9b9d-a56dcc4e8fb6/dashboard?cs_tk=AjRUjGetABhfPH5lvV0AAXicyyvNyQEABF8BvEdF089qzNwql_-zacPIjyw%3D&utm_campaign=d87a1005fffd494caa5ff366df4764aa&utm_medium=email&utm_source=petition_published_onboarding_0&utm_term=cs

How do we see the references to this informative article?

Hi Judy, footnotes for articles are currently not displaying due to a website update but we are working on this. Will let you know when we get them back up. Many thanks

Hi Judy, you will see the footnotes are now back

Worst piece of Legislation in English History.