Finally, an official report on deaths in police custody which places the experience and perspective of the bereaved families at its heart.

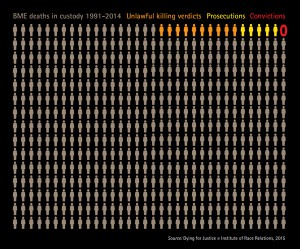

In 2015, the IRR published Dying for Justice, the result of an examination of over 500 cases of BAME deaths in custody which had led to only five prosecutions and not a single conviction of an officer or official, seriously undermining families and communities’ faith in the police and the criminal justice system. It is heartening to see how closely the conclusions and recommendations of Dame Elish Angiolini’s review into deaths in custody,[1] published this week, correspond with our own concerns and findings.

In 2015, the IRR published Dying for Justice, the result of an examination of over 500 cases of BAME deaths in custody which had led to only five prosecutions and not a single conviction of an officer or official, seriously undermining families and communities’ faith in the police and the criminal justice system. It is heartening to see how closely the conclusions and recommendations of Dame Elish Angiolini’s review into deaths in custody,[1] published this week, correspond with our own concerns and findings.

Dame Elish’s report is in some respects narrower than ours, covering as it does only deaths in police custody and not in prison or immigration detention, and in some respects it is wider, looking at all deaths, not just those of BAME individuals. She finds that a disproportionate number of people who died following police use of force were from BAME communities, and that such deaths, in particular of young Black men, resonate with the Black community’s experience of systemic racism, reflecting wider concerns about discriminatory over-policing, stop and search, and criminalisation. She notes, too, the wider social and political context, which includes the stereotyping of young Black men as ‘dangerous, violent and volatile’, misinformation in the media about the deceased and their family, and the lack of real accountability on the part of the police. (A strange and anomalous error in the report is the repeated mis-naming of Sir Iain McPherson, instead of Sir William Macpherson, as the author of the groundbreaking Macpherson report on the police investigation of the death of Stephen Lawrence – although Dame Elish is clearly familiar with Sir William’s conclusions on institutional racism.)

In her report, she includes the recommendation that ‘where there is evidence of racist or discriminatory treatment or other criminality or misconduct, police officers must be held to account through the legal system’. She also calls for statistics on use of force and restraint to include ethnicity, as they did before 2009, and for Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) monitoring of ethnicity in relation to arrests, use of force and deaths, with the inclusion of Gypsy Roma and Traveller communities in ethnic monitoring.

End preferential treatment for police suspects

The introduction to the report has a quote from Rev. Jesse Jackson as its epigraph: ‘Those who have the most power must be the most accountable’. The report goes on to demonstrate how that situation is often reversed when it comes to deaths in custody. It carries a strong recommendation that police must be held to account, on an individual and corporate basis, where restraint is unnecessary, disproportionate or excessive. Accountability is to be achieved operationally through mandatory recording of each use of force, including methods, and the ethnicity and mental health of the subject. Police engaging with the public should wear body cameras, and CCTV should be introduced nationally in vans. Failure to ensure proper functioning of cameras should be a disciplinary offence. In the chapters on the IPCC and on investigation of deaths, the point is repeatedly made that police suspects should not be treated more advantageously than civilian suspects – in matters such as pre-interview disclosure and lengthy delays in interviewing police, enabling officers to confer on the evidence they present when they are finally interviewed. The report recommends interviews with officers (who would have a duty of candour, unless they are formal suspects) as quickly as possible after the events, and separation of officers with a ban on communication with each other until they have made statements. It also recommends that disciplinary action be made more transparent, pursuing officers after retirement if necessary (this has been legislated for in the Policing and Crime Act 2017); local forces should justify decisions to keep officers in post pending proceedings; and sanctions for misconduct should be meaningful, to avoid the impression that officers are above the law.

The fact that there has not been a single successful prosecution of a police officer for murder or manslaughter, despite a number of inquest verdicts of unlawful killing, ‘does not prove’, the report says, ‘that the criminal justice system has failed to deliver justice, but it goes to the heart of why families so often feel let down by the system’. Dame Elish discusses reasons such as unconscious pro-police bias or fatalism (‘juries won’t convict police’) for Crown Prosecution Service decisions not to prosecute in the face of unlawful killing verdicts or clear evidence of wrongdoing, but makes no finding. She does point out however that the CPS has not yet used the Corporate Manslaughter Act, which came into force in September 2011, to charge a force, although a prosecution would draw attention to systemic failures and ensure accountability at senior levels.

The fact that there has not been a single successful prosecution of a police officer for murder or manslaughter, despite a number of inquest verdicts of unlawful killing, ‘does not prove’, the report says, ‘that the criminal justice system has failed to deliver justice, but it goes to the heart of why families so often feel let down by the system’. Dame Elish discusses reasons such as unconscious pro-police bias or fatalism (‘juries won’t convict police’) for Crown Prosecution Service decisions not to prosecute in the face of unlawful killing verdicts or clear evidence of wrongdoing, but makes no finding. She does point out however that the CPS has not yet used the Corporate Manslaughter Act, which came into force in September 2011, to charge a force, although a prosecution would draw attention to systemic failures and ensure accountability at senior levels.

Recommendations

There are 110 recommendations in all. The report considers, and makes detailed recommendations for ensuring recognition and proper and safe treatment of severely intoxicated people, those with mental health issues, those at risk of suicide, children, women and other potentially vulnerable detainees, and on the sharing of responsibilities for protection and care between police and NHS workers.

Important recommendations include:

- Police practice and training must recognise that all restraint, particularly of mentally ill or vulnerable people, can kill. A whole chapter is devoted to the dangers of restraint, particularly prone restraint which continues to be used, and causes death through positional asphyxia, despite repeated reviews and warnings;

- The Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC, to be renamed and rebooted in January 2018 as the Office for Police Conduct) needs to demonstrate real independence from the police by phasing out the employment of ex-police officers as lead investigators;

- Investigative delays need to be reduced, and the quality of investigation enhanced. Measures to achieve this include the creation of a specialist Deaths and Serious Injuries unit within the IPCC; urgent attendance of an IPCC officer at the scene to preserve the integrity of evidence, as would be done in other homicide investigations; separating the officers involved until they have made statements, and prohibiting conferral, to prevent collusion; setting deadlines for evidence gathering; early and regular liaison between relevant supervisory bodies, eg, the IPCC, the CPS and the Health and Safety Executive, to decide on prosecutions;

- The experience of families needs to be improved. Measures to achieve this include prompt notification of the death, timely and regular communication of information (including on specialist support and legal rights); provision of bereavement counselling; free, non-means-tested legal advice and representation for the immediate family of the deceased; involvement of families in police training and awareness exercises;

- A national coroners’ service and specialist coroners dealing with deaths in custody, ensuring expertise, independence, promptness, disclosure of relevant documents to families, and consistency of service.

Another important finding is the failure by statutory agencies to learn lessons from previous deaths. Dame Elish notes the importance of coroners’ Preventing Future Deaths reports, but observes that they are not widely disseminated, are not easy to find on the judiciary website and have no mechanism for follow-up to check that recommendations have been acted on. She recommends a national framework for the dissemination of PFD reports and thematic reports by eg, the IPCC, the Independent Advisory Panel on Deaths in Custody (IAP) and the College of Policing, with a follow-up mechanism to ensure that practices change as a result.

Learning from bereaved families

This report owes a huge amount to the families of those who have died in police custody or at the hands of the police. As Dame Elish acknowledges, their campaigns to find out the truth behind the death of loved ones – which started following the death of Blair Peach in Southall in 1979, and led to the formation of Inquest as a charity which would help and support such families – have led to many reforms in police training and awareness, the investigation of deaths in custody and the establishment and improvement of accountability measures. Inquest, whose director Deborah Coles was appointed expert adviser to the inquiry, ensured that the experience of families was central to the inquiry, both through its own evidence and through two Family Listening Days, when families spoke of their experiences at each stage, from the delays in being told of the death of their loved one right through to the endless delays in investigation, lack of communication, lack of disclosure of evidence, difficulties in getting legal aid and representation for the inquest, hostile and aggressive cross-examination by police barristers, and above all, the lack of accountability for the death, and the one-sidedness of the process. All of this finds its way into the report, which recommends the use of families’ experience in training for police and statutory agencies and includes as an annex Inquest’s report of the family listening days, vividly recreating the families’ callous treatment at the hands of officials so concerned with self-protection they forgot basic humanity.

The government response

Though the Home Office sat on the report for over ten months before publishing, its own response, published on the same day as the report’s release, does commit it to implementing some of the recommendations:

- For families: A presumption is to be created in the legal aid guidance that bereaved families will be entitled to legal aid for death in custody inquests. The recommendation not to means-test legal aid in such cases is not followed; instead, legal aid authorities (who have a discretion to disregard the means test in individual cases) will be asked to consider the distress of bereaved families in having to produce evidence of means. The Lord Chancellor will further consider legal aid and means-testing for inquests next year. Other measures to improve the process for families include working with coroners to ensure they are notified of the post-mortem, are able to have access to the body as soon as possible, are provided with the fullest possible information on legal and practical matters and availability of support services;

- Limiting use of police cells: The use of police cells as ‘places of safety’ for mentally distressed minors is to be banned (already legislated for in the Police and Crime Act 2017), and their use for mentally ill adults limited as much as possible;

- IPCC: The IPCC (to be renamed the Independent Office for Police Conduct in January) is to have more powers and greater autonomy and independence from the police, with the right to initiate investigations and to reopen them, and powers to debar former police officers from specified roles (all these measures are contained in the Policing and Crime Act 2017, not yet in force);

- Independence: Independent legally qualified chairs have already been appointed for police misconduct proceedings, with greater independence in decision-making in such cases, and legislation will require future determinations of proceedings to be published in full;

- Pursuing the police: Misconduct proceedings will be initiated or continued after an officer has left the force, and a Police Barred List will be published to prevent former officers obtaining police employment elsewhere (in the Policing and Crime Act 2017, not yet in force).

The government is also developing a new duty of cooperation with IPCC investigations for police officers, to ensure a full and clear account, and supports Dame Elish’s no conferral recommendation, although makes no commitment on separation of officers.

Of the report’s other findings and recommendations, those relating to police training and monitoring on use of force and restraint are met by reference to new training on safe restraint and a new emphasis on ‘containment’, including de-escalation, and the collection of improved and more inclusive use of force data since April 2017 (including ethnicity of the subject, as well as the type of force and reason for it). The response details training in dealing with the vulnerable groups identified in the report. A ministerial council will consider further recommendations on healthcare, inquests and support for families, and on issues such as learning from previous case reports.

Campaigners’ responses

In a press release issued simultaneously with the Angiolini report, INQUEST director Deborah Coles described the report as ‘seminal’ and a hugely important opportunity to bring about changes that could save lives. She pointed out that ‘The value of this report must ultimately be judged by the changes it brings about.’ The United Families and Friends Campaign (UFFC), which has campaigned for decades for many of the changes recommended by Dame Elish, made a similar point in its statement: ‘the report and its findings are not worth the paper they are written on unless meaningful action is taken. Time after time we hear the police say ‘lessons will be learnt’ but yet avoidable deaths in custody keep happening.’ UFFC called on home secretary Amber Rudd to convene an urgent meeting between the families of those who have died in police custody and the ministerial council which is meant to take matters forward.

It was Theresa May’s meeting, as home secretary, with a number of bereaved families that led to this review. Full and wholehearted implementation of its recommendations could transform policing, massively reduce deaths in custody and ensure speedy, thorough, independent investigations and appropriate, transparent criminal and/or disciplinary action, with the full involvement of bereaved families, in a system inspiring confidence.

People should not die at the hands of police. If they do, their families should not be subjected to the anguish of a slow, tortuous process in which the deceased is vilified, they are given no or little information, investigation appears designed to exonerate police rather than find out the truth, they are forced to spend life savings or sell property to have the legal representation at the inquest that the other parties have for free, and even inquest findings of unlawful killing result in no further action to bring officers to account. It isn’t rocket science. But unless the government really does take this report seriously, and is prepared to put resources into remedying the systemic flaws identified here, this burning injustice will not go away.

Related links

United Families and Friends Campaign

United Families and Friends Campaign on Facebook

United Families and Friends Campaign on Twitter

IRR report: Dying for Justice