An IRR News researcher speaks to scholars and campaigners across the country about the disproportionate use of Tasers on over-policed BME communities, as the IOPC announces an inquiry into widespread police discrimination.

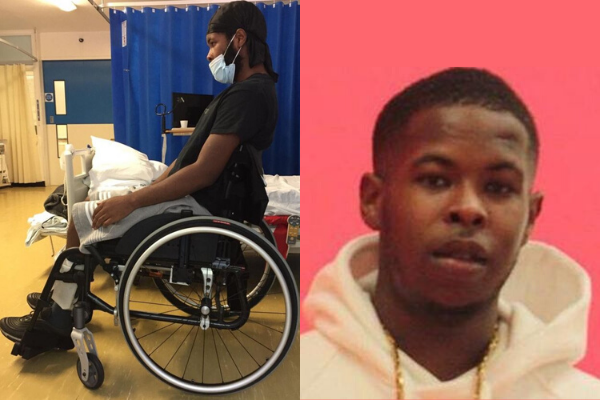

On 4 May in Haringey, the police tasered Jordan Walker-Brown, a then 23-year-old black man they were trying to detain as he jumped over a wall, leaving him paralysed from the waist down. Just two days later, a video circulated showing the police tasering another black man, Desmond Ziggy Mombeyarara, in front of his young son in Greater Manchester, who distressingly screams ‘Daddy’ whilst watching his father fall to the ground. Then, on 9 June, rapper Wretch 32 shared bodycam footage of the police entering the Tottenham home of his father Millard Scott in search of a suspect on 21 April. The footage shows the police tasering Mr Scott at the top of the stairs, resulting in the 62-year-old falling head-first down the flight of stairs. After the incident, the police said that the raid on Mr Scott’s home was ‘part of a long-running operation to tackle drugs supply linked to serious violence in the borough of Haringey’ – but the family maintain that the police did not search the house for drugs. Moreover, Mr Scott was not the suspect the police were pursuing – nor did he fit the description. Mr Scott is, however, black. This seemed to be justification enough to taser him, and therein lies the issue.

These three incidents are not isolated. Rather, they are emblematic of three key concerns: that Tasers are being disproportionately deployed against the black population; that Tasers have long-term, permanent consequences; and that Taser usage is rapidly increasing.

Disproportionate deployment of Tasers against the black community

Tasers were first introduced to the UK in 2003 for use by firearms officers ‘to fill the operational gap between the baton and the gun’, and were rolled out to non-firearms officers called Specially Trained Officers four years later. Since then, the UK has witnessed a rapid increase in the number of Taser-trained police whereby in 2019, 17,000 out of 123,000 police officers were Taser-trained in England and Wales. However, since their first appearance, the disproportionate use of Tasers against the black population has been an enduring issue. Across England and Wales, new analysis of Home Office figures found black people almost eight times more likely to have Tasers deployed against them compared to white people. Moreover, the increasing deployment of Tasers on BME children is a progressively disturbing matter, with 2019 statistics indicating that minors in 74 percent of Taser deployments in London were of BME background.

Disproportionate Taser usage against black people can be attributed to a combination of factors, namely: the persistence of racial stereotypes relating to black criminality; the over-policing of BME communities; and institutional racism in policing – all of which can be grouped together under the banner of structural racism. The potency of the black criminal stereotype is epitomised by the case of Judah Adunbi, a black race relations adviser for the police who was tasered by his own police force after being mistaken for a wanted man – and who, a year later in 2018, was mistaken by the police for the same wanted man again. Taking this into account, we see how racially disproportionate Taser deployment can be understood as both a product and an intensifier of structural racism. The way in which Tasers entrench structural racism is evidenced in a recent analysis by Dr Michael Shiner, associate professor at LSE and member of StopWatch, which demonstrates that disproportionality between black people and white people is markedly higher when the police use high-degree force, such as Tasers and firearms, compared to low-degree force.[1]

There has also been significant controversy over the growing use of Tasers against those with mental health problems, given the significant pain (the UN Committee Against Torture determined that the pain inflicted by Tasers is intense enough to be considered a form of torture), distress and health problems they can induce. In fact, in the year from 1 April 2017, Tasers were used against mental health patients in healthcare settings 96 times. It is a well-known fact that black people are overrepresented in mental health statistics and systems, illuminating how multiple forms of inequality coalesce in the experiences of black Britons, rendering them increasingly exposed to the dangers of Tasers. Addressing how Tasers exacerbate intersecting inequalities, Dr Kerry Pimblott, lecturer at the University of Manchester and member of Resistance Lab, said, ‘Tasers are used by police in ways that reinforce systemic racism and other interlocking inequalities with disproportionate and potentially lethal consequences for black communities and individuals with mental health conditions in particular.’[2]

The long-term impacts of Tasers

The recent case of Mr Walker-Brown, paralysed by a Taser, demonstrates the fact that Tasers can result in lifelong injuries – contradicting the Metropolitan Police’s definition of Tasers as a weapon which ‘temporarily interferes with the body’s neuromuscular system’. The Metropolitan Police also define Tasers as a ‘less lethal’ ‘single shot weapon’ – yet 18 people in the UK have died after being tasered since 2003, and coroners have identified Tasers as having caused or contributed to the deaths of Marc Cole, Jordan Begley and Andrew Pimlott. Clearly then, Tasers are indeed lethal, and when not lethal, can engender long-term health problems. Potential long-term impacts of Tasers include injuries from uncontrolled movements and Taser probe penetration of sensitive body parts.

It is important to note that Tasers can cause not only long-term physical harm, but also long-term psychological trauma for the individuals affected and the communities they belong to. As such, Tasers contribute to existing police practices such as stop and search which induce trauma collectively, principally within BME communities. In an open letter to the Greater Manchester Police regarding the Taser incident involving Mr Mombeyarara, the Northern Police Monitoring Project highlighted the issue of collective trauma, saying that the ‘The taser appears to be deployed without warning or justification, and without any regard to the lasting impact that witnessing such events will surely have on the child, and our wider communities – particularly those that are already familiar with police violence.’ Similarly, a parent articulated to the NGO ‘Kids of Colour’ how the incident added to extant trauma within the black community:

As a mother, I would like to say that it has really traumatised me. It’s really made me feel as a mother of 3 black sons aged 21, 15 and 10 that there’s no protection or support for them. I just feel very scared and fragile at a time like this, that certain systems are not taking accountability of these behaviours. We keep seeing these behaviours over and over again, and the trauma it has for our children and young boys in the community, we need to find a better way that police are responding to young black males. It’s out of hand, it’s disrespectful. My son is really upset by it, he’s 15.

In an interview, Dr Rebekah Delsol, Programme Manager for the Fair and Effective Policing Project at the Open Society Justice Initiative and member of Stopwatch, remarked on the worrying near-absence of research concerning the psychological trauma Tasers cause to BME communities. In light of this, she called for research to be carried out on the diverse ways in which Tasers engender trauma within over-policed BME communities, stressing that research should be realised by BME academics embedded within those communities.

Policing: inertia and impunity

On 24 March 2020, rights groups Open Society, Inquest, Stopwatch and Liberty announced their resignation from the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) independent Taser advisory group in protest, stating that no significant steps are being taken to address the disproportionate use of Tasers against BME people. In a joint resignation letter to the NPCC, the rights groups explained, ‘We are increasingly concerned that the NTSAG [National Taser Stakeholder Advisory Group] is now regularly sidestepped, while the group’s existence is relied on to legitimise current use of Taser.’

The fact that three Taser incidents – in Tottenham, Greater Manchester and Haringey – occurred within six weeks of the rights groups quitting the police body underscores the police’s continual refusal to acknowledge and tackle the excessive discharge of Tasers against the black community. Part of the reason for the police’s inertia to concerns regarding disproportionality can be attributed to their apparent impunity in unjust Taser usage. The statistics show that police officers are practically never suspended or arrested for wrongful use of Tasers. In fact, since 1990, 1,745 people have died in police custody in the UK, but not one police officer has been successfully convicted of homicide or assault.

Concerning the Taser incidents involving Mr Walker-Brown and Mr Mombeyarara, the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) has stated that it will conduct criminal investigations into both cases. Regarding the Taser incident involving Mr Scott, the Metropolitan Police’s review found ‘no indication of misconduct’ and said the incident did ‘not meet the criteria for a referral to the IOPC’. Despite Wretch 32 sharing the footage on Twitter, which gained nearly 2 million views, drawing widespread criticism from the likes of Sadiq Khan and Amnesty International UK and leading the IOPC to reassess the incident, the IOPC ultimately decided on 15 July that they will not conduct a criminal investigation into the Taser incident of Mr Scott.

Though the cases of Mr Walker-Brown and Mr Mombeyarara will be investigated, it should be noted that an IOPC criminal investigation does not necessarily mean that criminal charges will follow – and given that police are rarely held accountable for their actions, the likelihood of this occurring is not promising. Thus far, none of the police officers involved in these three cases have been suspended. Deborah Coles, the director of Inquest, said, ‘The test of the IOPC will be what comes out of those investigations and whether or not it results in anybody being held accountable.’

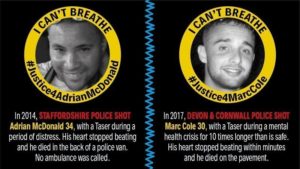

Considering the police’s resistance to address disproportionate Taser usage combined with their evident impunity, it becomes clear that institutional racism is deeply embedded within the structures of policing as well as within the bodies that regulate it. Speaking about how the IOPC has consistently let down the families of those who died in police custody, Lisa Cole, sister of Marc Cole, who died after being tasered whilst suffering a mental health crisis in 2017, said,

‘There’s no accountability. That comes back to the government. The government protects these officers at all costs. And I’ll say it again, it’s another example of state violence. You know, it’s the systemic refusal and the systemic discriminatory policing practices [that] are protected by institutionally racist systems. We cannot talk about policing and accountability unless we talk about the systems that deliberately protect them.’

Growing frustration about the failings of the IOPC coincided with the Black Lives Matter protests in the UK, part of the worldwide movement since the death of George Floyd. As a result, the United Families and Friends Campaign, a coalition of family and friends of people who died in state custody, of which Lisa Cole is a member, drew up a plan calling for the abolition of the IOPC, amid concerns that it is not truly independent, and for the immediate suspension of police officers implicated in deaths until investigations are concluded.

The paradox: increasing Taser usage

Despite the deaths caused by Tasers, evidence of racially disproportionate use, and the severe lack of research on their physical and psychological impacts, in September 2019 the government announced that it would be spending £10 million on arming 10,000 more police officers across England and Wales with Tasers. This is cause for great concern, as the use of Tasers increased by 39 percent in 2019 alone as more officers were equipped with them.

The government’s mass Taser roll-out plan has been widely condemned by rights groups. Rosalind Comyn, policy and campaigns officer at Liberty, drew attention to how greater Taser usage will drastically change the nature of policing, stating that the increase ‘risks escalating, rather than reducing, violence on our streets and will further corrode the fractured relationship between police and the communities they serve.’ This point is highlighted by a 2018 study which demonstrates that police officers carrying Tasers are causally linked to a 48 percent increase in the use of force. In this vein, many groups, such as Liberty, Amnesty International UK and StopWatch, have highlighted the need to limit Taser usage to ‘highly-trained specialist officers’ and ‘critical situations’.

Rights groups, academics and family campaigns have also questioned the government’s decision to allocate £10 million to a Taser roll-out scheme as they argue the money could be better spent investing in oft-neglected areas such as health, education and housing services of vulnerable communities. Speaking through the concept of defunding the police, Rebekah Delsol, Lisa Cole and Deborah Coles all emphasised that spending £10 million on a Taser roll-out scheme will further perpetuate violence within deprived and BME communities, whilst investing holistically in those communities would address the underlying causes of violence, thus reducing it.

Towards change?

Responding to the recent spate of Taser deployment against black men and mounting pressure from rights groups and the Black Lives Matter movement, on 12 June the National Police Chiefs Council announced that it will commission an independent review into racially disproportionate Taser usage. Whilst an independent review may signify a step in the right direction for some, there is still a great deal of doubt amongst the family members of those who died in police custody. Lisa Cole voiced her mistrust, questioning how independent the researcher appointed would be, saying, ‘Anybody who says they’re independent and working on behalf of investigating the police or independent reviews, we seriously question. How independent are they?’ Deborah Coles added that it is imperative that the chosen researcher in any review consults the families of those who have died or suffered lasting injuries after being tasered, in order to understand and address their concerns.

Moreover, mirroring David Lammy’s recent call to implement changes recommended by Angiolini, Baroness McGregor-Smith, Lammy’s own and the Home Office Windrush Review to tackle structural racism in the UK, Lisa Cole stressed that beyond reviewing disproportionate use of Tasers, it is absolutely crucial that the recommendations are implemented. To this effect, the families of Marc Cole and Adrian McDonald started an ‘End Taser Torture’ campaign in June 2020 to demand the enactment of policy changes, such as the prohibition of ‘prolonged and multiple Taser Electrocution’ on vulnerable persons and the complete revision of police Taser training. In an interview, Wayne McDonald, brother of Adrian McDonald, also stated that the police should seek medical assistance immediately for anyone tasered longer than five seconds. This is absolutely critical for Wayne McDonald, as Adrian was tasered for 25 seconds according to his family, and died in the back of a police van unattended to, begging for assistance whilst saying ‘I can’t breathe’.

Reflecting on the views of researchers, family members and campaigners who talked to IRR News, it is clear that disproportionality is not the only issue related to Taser usage. In and of itself, it is evidently a problematic feature of British policing that unequivocally necessitates further scrutiny and immediate systemic change. Taking a step further, Resistance Lab and Northern Police Monitoring Project have expressed their support for abolishing Tasers altogether, citing their lethality and ‘an ever-growing body of evidence that the police simply cannot be trusted with such power, particularly where Black and Brown communities are concerned’.[3] If no action is taken, then it is inevitable that the incidence of Taser-induced injuries, deaths and trauma will rise. In the words of Wayne McDonald, ‘We have to do something, and now is our time’.

In 2009 Howard Swarray was tasered by police because he wouldn’t comply with commands. He was in the grip of an epileptic fit.

In 2012 Colin Farmer was tasered by police because they thought he had a weapon. He was blind and had a white stick.

In 2013 Andrew Pimlott was tasered by police who knew he was in the grip of a mental illness episode because he had doused himself in petrol. He died in hospital.

They simply turn to the heaviest weapon to hand.

The author has meticulously presented the plight of the ethnic minorities and highlighted the trauma experienced by them. It is unfortunate that the law enforcement machinaries in the developed countries are also adopting third degree techniques to combat criminals leave alone aggressive criminals. Police brutality is a common phenomenon all over the world which has to be properly investigated and the erring officers charge sheeted and see that it culminates in the trial and conviction. The victim should also be a party to those proceedings so that they have a say and compensated duly at the end of trial.

I, endorse 100%with the view expressed by

Mr. T.S. Subramanian.

A very sad state of affairs existing in U K. P police which I have never imagined. I genuinely thought they were friendly.