Swiss nativist parties have drawn a new line in the sand, winning the admiration of those campaigning to end EU free movement rights.

Anti-immigration and nativist movements across Europe are increasingly turning their ire on eastern European workers exercising free movement rights under EU foundational treaties. UKIP’s position – that ‘unfettered free movement from the poorest countries on the continent into the more advanced ones with higher living standards and welfare entitlements is unsustainable’ – is now supported by a growing number of mainstream centre-right and right populist parties. The latest standard-bearer for Europe’s anti-immigration movements is the Swiss People’s Party (SVP), the strongest and one of the wealthiest rightwing populist parties in Europe[1]. In February, the SVP/UDC launched a referendum to ‘stop mass immigration’ into Switzerland. Supported by the small ultra-conservative Federal Democratic Union and a number of cantonal-based groups, such as the Movement for the Citizens of Geneva (MCG) and the Committee of Egerkingen, the motion was narrowly passed with 50.3 per cent of the vote.

In fact, despite its catch-all phrase about ‘mass immigration’, the referendum was not specifically aimed at migrants from the ‘poorest countries of the Continent’ (to borrow UKIP leader Nigel Farage’s phrase). Instead, it was directed against all EU workers, including those from the prosperous core countries. The wording expressly called for the ‘reintroduction of quotas for immigrants from the EU’. The fact that Swiss nativists aimed their arrows at ‘natives’ from all other EU countries (including the most prosperous ones) seems to have passed the European extreme Right by. From the Front National (FN) in France and the Progress Party in Norway, to Alternative for Germany (AfD) and UKIP, have come warm words of support for this victory for ‘direct democracy’, and vindication of the true desires (and fears) of the average citizen. According to Farage, the ‘Swiss people have taken advantage of their position outside the European Union to set their own immigration rules in their own national interest and I congratulate them for doing so… Were the British people to be given their own referendum on this issue then the result would be the same – but by a landslide.’

Background to the referendum

Switzerland is not in the EU, but it is part of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) which gives it preferential access to the European single market but only if it adheres to seven agreements, known as ‘bilateral ties’, including an agreement to allow EU/ EFTA citizens to live and work in Switzerland. If any one of these accords is broken, all seven agreements fall. Since the late 1990s, there has been an increase of EU nationals working in Switzerland, particularly skilled workers from the bordering countries of Germany, Austria and Italy. Recently, grassroots movements have formed to oppose cross-border migration, one such being the MCG which has twenty seats in the Geneva cantonal parliament and is cutting into the SVP vote. The MCG campaigns to drive back the frontaliers (cross border commuters), who are blamed for lowering salaries, the real estate bubble, higher rents, and overcrowding on transport systems.

Switzerland is certainly feeling the winds of globalisation. Yet the winds do not all blow one way. Big business and finance capital, not ordinary people, reap the benefits of access to the EU market (Switzerland exports approximately 60 per cent of its goods, including high value exports related to the pharmaceutical and chemical industries, to the EU). Inward foreign investment, cooperative research and the relocation of many multinationals, particularly to Geneva, are all other facets benefiting the Swiss economy. In fact, Switzerland is a very wealthy country, and one whose wealth was built, in the post-war period, on a system that strictly regulated migrant labour. Migrant workers from southern Europe and then the Balkans were encouraged to come to Switzerland after the Second World War, but only as guest-workers; with no rights to settlement and renewable residence permits they formed a classic exploitable reserve army of labour. Swiss attempts to make use of migrant labour while, at the same time, maintaining a system of national preference in employment laws and a strict approach to citizenship (it has the harshest citizenship laws in the EU/EFTA area) came under pressure from the 1970s onwards and gradually reforms were brought in, largely under pressure from the international community as Swiss family reunification laws, in particular, were seen to breach international legal norms.

Another well-known facet of Switzerland is its system of ‘participatory democracy’ (or plebiscitary democracy) under which citizens may petition for a referendum on any subject, which can be put to a referendum if those who initiate petitions amass the required 100,000 signatures. In the 1990s, as the Swiss immigration and asylum system came under increasing scrutiny, the SVP turned to the referendum system in a bid to preserve the status quo and keep immigrants and asylum seekers from the East and South out. There have been at least fifteen referenda on immigration and asylum issues since 1999. One which was condemned by the UN for racism was the 2007 referendum for the deportation of foreigners where the SVP mass circulated a racist poster that showed three white sheep standing on a Swiss flag, with one of the sheep kicking out a black sheep with a flick of its back legs.  In November 2009, Switzerland became the first country in Europe to vote to curb the religious rights of Muslims, following the success of the SVP referendum to ‘Stop the Construction of Minarets on Mosques’ which used posters of minarets portrayed as bayonets attacking the Swiss countryside. If there is a country where referenda have unashamedly been used to institutionalise xeno-racism (as well as break international norms on asylum rights), surely that country is Switzerland. In the latest referendum, national pride was also built into the nativist argument as the EU (as well as the US and the OECD) had angered Swiss financers by attacking illegal practices and the lack of transparency within the Swiss banking sector.

In November 2009, Switzerland became the first country in Europe to vote to curb the religious rights of Muslims, following the success of the SVP referendum to ‘Stop the Construction of Minarets on Mosques’ which used posters of minarets portrayed as bayonets attacking the Swiss countryside. If there is a country where referenda have unashamedly been used to institutionalise xeno-racism (as well as break international norms on asylum rights), surely that country is Switzerland. In the latest referendum, national pride was also built into the nativist argument as the EU (as well as the US and the OECD) had angered Swiss financers by attacking illegal practices and the lack of transparency within the Swiss banking sector.

Different constituencies, different messages

In launching the referendum, the SVP had a veritable ‘war machine’ at its disposal. Its most high-profile politician is the billionaire entrepreneur and former lawyer Christoph Blocher, who donated 2.45 million euros to the ‘Stop Mass Immigration’ campaign. Le Matin has in the past described the SVPas a party with ‘incomparable financial means, dedicated politicians and simplistic but terribly efficient messages’.

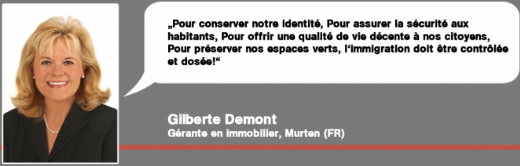

Different messages were taken to different audiences: protect Switzerland from EU social dumping and preserve well-paid jobs and affordable housing; immunise Switzerland from Euro sickness; keep foreigners out; protect Switzerland from floods of Muslim migrants and delinquent foreign criminals. The first major target for the message was the so-called ‘squeezed middle’, the middle classes alarmed by lay-offs in banks, Swiss pharmaceutical companies moving to Germany, a real estate bubble fuelled by rich foreigners buying property, and the OECD attack on the Swiss banking system. The MCG campaign slogan is ‘Neither Left nor Right, Geneva First’.  Its fifteen-point charter outlines a programme of national preference while simultaneously pledging the party to green policies and a redistributive economic and social approach. But while the MCG committed itself to national preference for ‘unemployed citizens’, it promised a tough approach to those who exploited the benefits system and a clampdown on clandestine immigration.

Its fifteen-point charter outlines a programme of national preference while simultaneously pledging the party to green policies and a redistributive economic and social approach. But while the MCG committed itself to national preference for ‘unemployed citizens’, it promised a tough approach to those who exploited the benefits system and a clampdown on clandestine immigration.

The rural/urban divide

Another constituency targeted for the ‘yes’ vote were the rural conservatives, for it was in the countryside that the strongest support for the minaret ban proposal was gained. An analysis of voting patterns in the referendum shows that there was a clear divide between voting trends in rural and urban areas, with rural areas (largely, but not wholly, in the German-speaking east with its power-base of small farmers and craftsmen) predominantly voting to cap immigration and urban, more multicultural areas, predominantly voting against the motion.

With its roots in the farmers and traders movements of the twentieth century, the SVP is particularly adept at manipulating this conservative rural vote. The IRR has previously warned in Pedlars of Hate that a new geography of racism is emerging in Europe, and that the political climate is most explosive in conservative rural areas. This is true, both in Switzerland, probably the European country where the highest percentage of the population live in rural areas, and in France. Here the FN’s renaissance is fuelled by economic decline and feelings of neglect and isolation in disconnected villages.

Despite its attempts to present itself as speaking up for the ‘common man’, the SVP’s base is actually among wealthy rural elites. Residents of Alpine villages may be completely integrated into modern high-tech life, but they have a strong belief in preserving tradition and resist newcomers, sentiments that the SVP exploits to perfection. In its referendum material, the SVP argued that it was the only party capable of speaking up for the ‘masses’, one that could protect the average citizen from a bloated state that cared more for a cosmopolitan elite than traditional Swiss culture. In this way the SVP operates in line with many of Europe’s wealthy anti-immigration political parties that exploit the electorate’s fears of the loss of cultural identity that arises from globalisation and the economic vulnerability of the ‘average worker’. It links declining wages and living standards not to regressive taxation policies or the dismantling of welfare states, or the failure to spread the benefits of migrant labour equally, but to the mere presence of immigrants.

When it comes to analysing why the referendum succeeded, political commentators have also pointed to the weak (or lack of) arguments put forward by the opposition parties such as the FDP, the Social Democrats, as well as the trades unions, all of which opposed the proposal to cap immigration.

It is certainly true that the opposition were complacent; just as with the referendum to ban minarets, they were over-confident that they would win and failed to commit necessary resources to the campaign for a ‘No’ vote. Their arguments, which had no appeal to rural voters, rested on a repeated invocation of the damage that the immigration cap would do to business and the future of the Swiss economy. Some political commentators argued that this just served to alienate rural voters further, pushing them into the pro-motion camp. However, to blame the opposition solely for pushing the rural vote into the ‘Yes’ camp is to ignore the very real appeal of Islamophobia and racism to the rural voter. Indeed, the Committee of Egerkingen even went as far as to call a press conference at which it predicted that there will be one million Muslims living in Switzerland by 2030.

Applause from the extreme Right

The result of the Swiss referendum puts Switzerland on a collision course with the EU. How that will be resolved remains to be seen. Blocher is unrepentant, suggesting that if the EU punishes Switzerland for voting against the ‘catastrophe’ of the free movement of people, Switzerland might reconsider the transit treaty that allows free passage from Holland to Italy, from one sea to another through the Gotthard Tunnel. Meanwhile, the leaders of extreme-right parties, seemingly unaware of the difficulties they may in future face travelling through Switzerland, have been applauding the ‘courage’ of the Swiss people or, in the words of the FN’s Marine le Pen, their ‘lucidity’ in casting their votes. There have also been calls for similar referendums to restrict immigration in other European countries. Heinz Christian Strache of the far-right Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) has publicly stated that, if a similar referendum were to take place in Austria, ‘the majority of people would announce themselves to be in favour of immigration quotas’, echoing UKIP’s Nigel Farage, as well as the Norwegian Progress Party’s (FrP) Mazyar Keshvari: ‘Norway should also organise a referendum on immigration. I’m completely certain that a majority wants to tighten up.’ A dangerous populism is growing, whereby demagogic politicians present themselves as representing the ‘will of the masses’ against out-of-touch, cosmopolitan and urban elites. All this is bound to place more pressure on centre parties to move on to the terrain of the likes of UKIP and the SVP. Already the UK’s Conservative Party has announced its election agenda to restrict both intra-European and international immigration through the enforcement of punitive measures relating to either the restriction of access to welfare and housing benefits, or through the administrative detention of asylum seekers. Cameron is clearly playing to UKIP voters, anxious about the party’s unexpected success in the English local elections in 2013 and the possibility that it will obliterate the Conservative vote in the European parliamentary elections in May. The revelation that the Conservative Party’s election strategist Lynton Crosby had suggested to David Cameron that the party should produce ‘a new policy to curb immigrants and benefits’ every week in the run-up to elections is proof of this bid to bridge the gap between the centre- and the extreme-Right. Just like the British Conservative Party, the French Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) is moving even further to the right on questions of immigration. Rachida Dati, the European deputy and candidate for the UMP, stated in response to the referendum, ‘I am mainly of David Cameron’s position to install immigration quotas, including intra-European immigration.’ With Cameron’s promise of a referendum in 2017 about Britain’s membership of the EU if the Conservative Party win the next general election, with (intra-European) immigration and the Human Rights Act at the forefront of the justification for bringing this motion to referendum, it is clear that the politics behind the Swiss motion to stop EU migration is not unique to Switzerland alone.

RELATED LINKS

Read an IRR Briefing Paper: Eliminating Electoral Racism

Read an IRR Briefing Paper: Direct democracy, racism and the extreme Right

Read an IRR Report: Pedlars of Hate: the violent impact of the European far Right

Read an IRR News story: Back to the future: Racism still rules

Read an IRR News story: How the extreme Right hijacks direct democracy

Read an IRR News story: Unabashed anti-migrant, anti-welfare election strategy

Remove my picture !!!