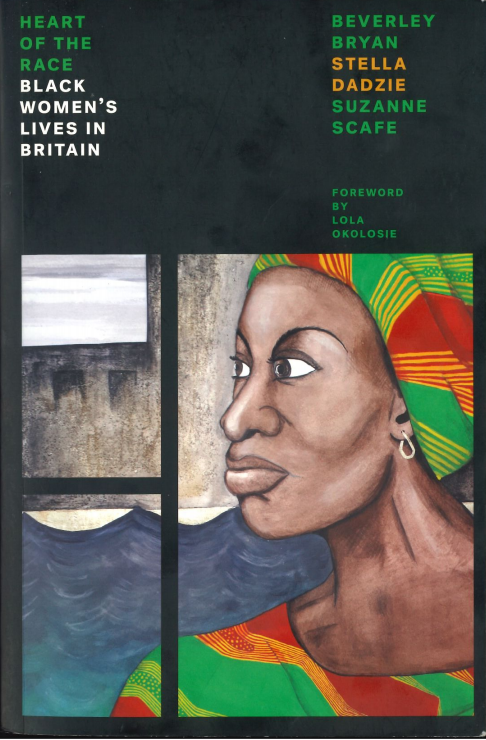

A seminal radical black feminist text, first published in 1985, which tells the story of black women’s experiences in Britain, has now been republished by Verso, at a time when we need it more than ever.

Born out of anti-colonial, feminist politics and black solidarity, young generations of activists have much to learn from The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain – about our history of anti-racism, the praxis of organising and a commitment to working collectively against racism and sexism.

From 1985 to 2018

Reading the book more than thirty years after it was first published, it is still (depressingly) as relevant as ever. As Lola Okolsie reminds us in the opening foreward to this new edition, ‘the struggles succinctly captured in The Heart of the Race continue to plague black communities in the twenty-first century’:

‘Black Caribbean and mixed white/black Caribbean pupils are three times more likely to face permanent exclusion from school…three quarters of young black men… have their DNA profiles in the Police’s national DNA database…unemployment rates among black women have continued to be consistently higher than for their white counterparts…most of the children living above the forth floor of England’s tower blocks are black or Asian.’

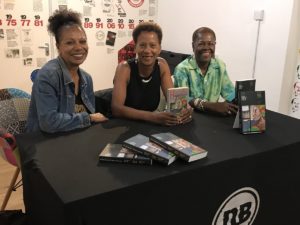

But at the book launch at New Beacon Books last week, there was a sense of hope, urgency and a feeling of having the collective power to change the world. All three authors, Beverly Bryan, Stella Dadzie and Suzanne Scafe were leading the discussion, chaired by Michelle Asantewa, co-founder of Way Wive Wordz, with a packed audience of both young and old, including Althea LeCointe, who was a leader of the British Black Panther Movement.

The collective ‘we’

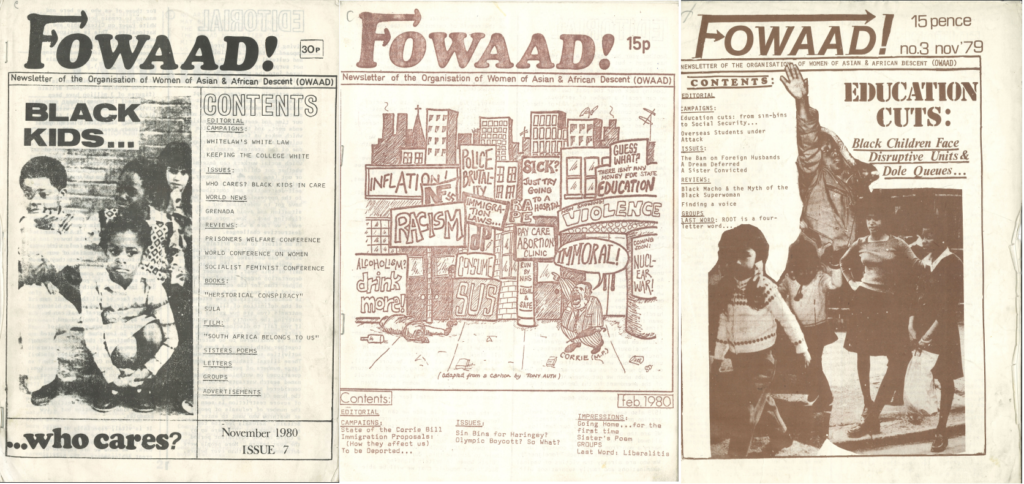

Organised into five chapters on women and work, women in education, women in health and housing, the history of women’s organising and questions of identity, the structure of the book is born out of discussions held by the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD), which all three authors were part of.

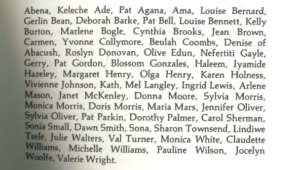

OWAAD was an umbrella organisation that campaigned from 1978-1982 on issues including immigration, domestic violence, policing, and health. The voices of many of the women involved with OWAAD and other community organisations such as Brixton Black Women’s Group were part of the collective effort to create the book – ‘the voices of Black women who have suffered because of racist and discriminatory practices in this country speak on every page’.

Images of OWAAD’s newsletter from IRR’s Black History Collection.

The Heart of the Race did not set out to be a seminal text, it was written by and for a community of women to tell their own story, ‘to give black women a voice when we had no voice’. The collective ‘we’ that speaks throughout the book is not only the voices of the authors and the women interviewed, but, as Suzanne Scafe noted at the book launch, ‘all the women that the book speaks to are also part of the book’.

Making clear the politics of solidarity that was rooted in an anti-colonial, anti-imperialist framework, the book shows how the commonality of experiences of imperialism and colonialism brought people together to fight a common cause. Racism comes in many forms, whether it be being subjected to virginity testing, as was the case for Asian women on arrival to the UK in the 1970s, or the administration of the contraceptive Depo-Provera (which can have serious long-term side-effects) to black women in the UK, the US and Third World countries ‘in the interests of controlling the numbers of “unwanted” black babies’, Asian and black women were united (and continue to unite) in the fight against racism and sexism.

‘It wasn’t about the individual, it was about working together’, academic Heidi Safia Mirza notes in the afterword of the new edition. Beverly Bryan echoed this at the book launch, ‘it’s not about the personal, it’s about the issue’.

‘It wasn’t about the individual, it was about working together’, academic Heidi Safia Mirza notes in the afterword of the new edition. Beverly Bryan echoed this at the book launch, ‘it’s not about the personal, it’s about the issue’.

‘Gains made are always momentary’

The issues the book raises are very much alive, and in many cases, the impact of state racism has intensified. But what has changed, as Stella Dadzie notes in an interview with the authors printed in the new edition, is that ‘you’ve got more visibility at the other end of the spectrum… more black women who are deemed to have made it’:

‘It’s as if people have lost sight of the class struggle. Yet if you look at women who are at the bottom of society, they’re still there, they’re still predominately black, they’re still dispossessed and they’re still…coping with the same old issues.’

What struck me when reading the book is the extent to which the conditions of oppression for people ‘on the margins’ – but who are fundamental to the working of society – have stayed the same. ‘Black women are still in unregulated jobs, still working in the caring stream without permanent contracts. Many of them are undocumented workers on zero-hour contracts they have no rights at all’, notes Suzanne. In many ways the conditions remain the same in 2018, but have shifted to affect an expanded group of people, mainly migrant women.

The chapter, ‘The Uncaring Arm of the State’ reveals the historical origins of racism in health and welfare systems. ‘We are today witnessing a growing erosion of our individual right to confidentiality’ in terms of health records, welfare and social security data, ‘hospitals now record our medical history and our immigration status’’ It’s chilling reading this now, when data sharing has intensified through ‘hostile environment’ policies, which are increasingly turning doctors into border guards.

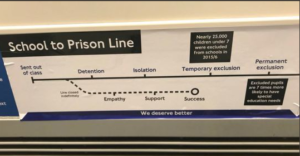

As state racism intensifies, so does the resistance, and the countless campaigns that have developed since the book’s genesis sprung to mind as I read it. The chapter ‘Learning to Resist’ exposes institutional racism in schools and particularly school exclusions that ‘entrench our position at the bottom of the ladder of employability’. The same structures exist today, but resistance has sprung up in new forms. Education not Exclusion put up ‘school to prison line’ posters on the Northern line on GCSE results day, a recent ad-hack which demonstrates the different ways young people are harnessing powers of design and social media to affect change.

The Heart of the Race gives a huge amount of insight into black women’s agency and activism in British history, and what we as young activists can learn from it. It underscores how black feminism must look beyond our own backyard and connect to global issues impacting black and brown women across the world. The anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist grounding is still urgent today. As Stella Dadzie notes in the closing chapter to the new edition:

‘In these crucial times we need to remember who we are, remember what we’ve come from, remember what we’ve achieved, and never let that be forgotten, because it gives us power, strength and vision. This is what feeds the enthusiasm and the energies of the next generation.’

Related links

The Heart of the Race, £6.00 special offer until the end of September

Find out more about the history of OWAD

Consult the Black History Collection