Rot At The core, a book about corruption and racism in the British Transport Police calls into question the validity of the recent apology from its current Chief Constable.

Last week the Chief Constable of the British Transport Police (BTP), Lucy D’Orsi, made a formal apology to the British African community for both its history of systemic racism and the egregious corruption of former BTP officer Derek Ridgewell. D’Orsi sought to paint the racism of the British Transport Police as belonging firmly to the past, but a June 2021 freedom of information request showed the BTP was still six times more likely to use force against Black people than white people.

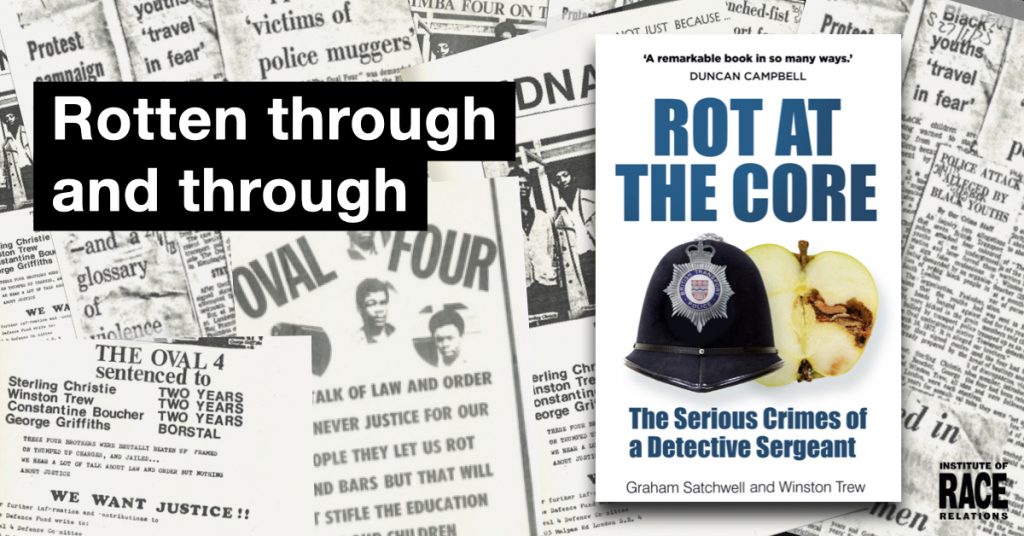

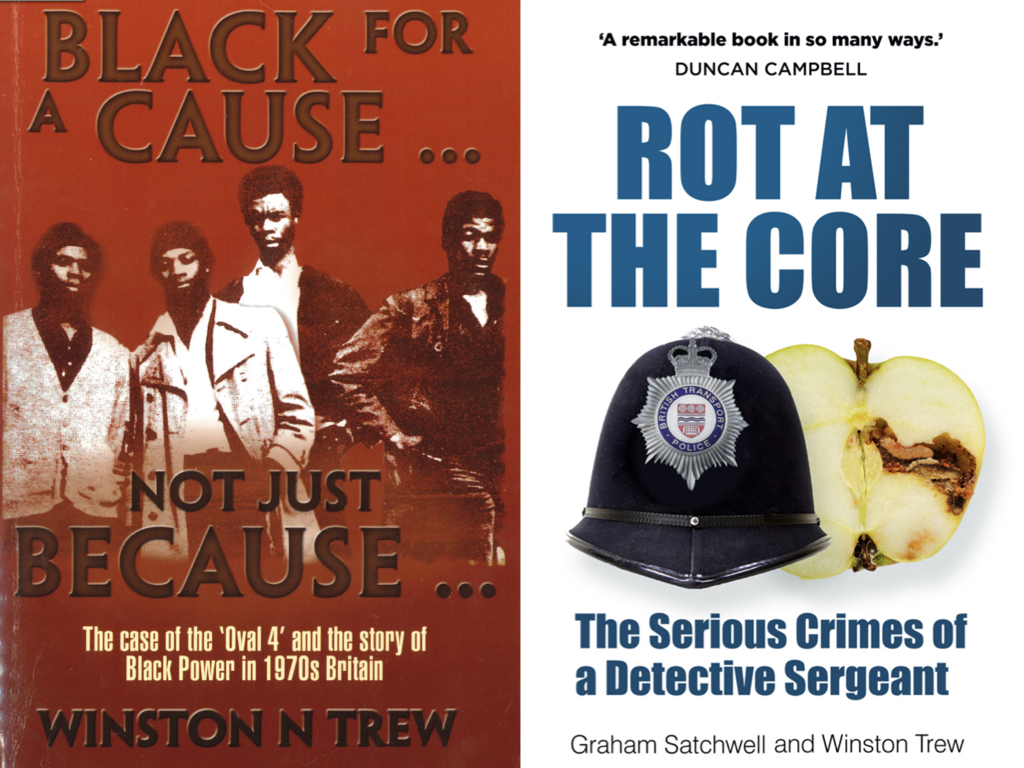

Copious historical evidence of the widespread racism of the British Transport Police, as well as endemic corruption is given in Winston Trew’s and Graham Satchwell’s book Rot At The Core: the Serious Crimes of a Detective Sergeant, published by The History Press. An unusual collaboration – Winston Trew is a former Black Power activist and one of the ‘Oval Four’ and Graham Satchwell a former BTP detective – the book examines the egregious corruption of Det. Sergeant Derek Ridgewell and its impact on the lives of two of his victims, Winston Trew and Stephen Simmons.

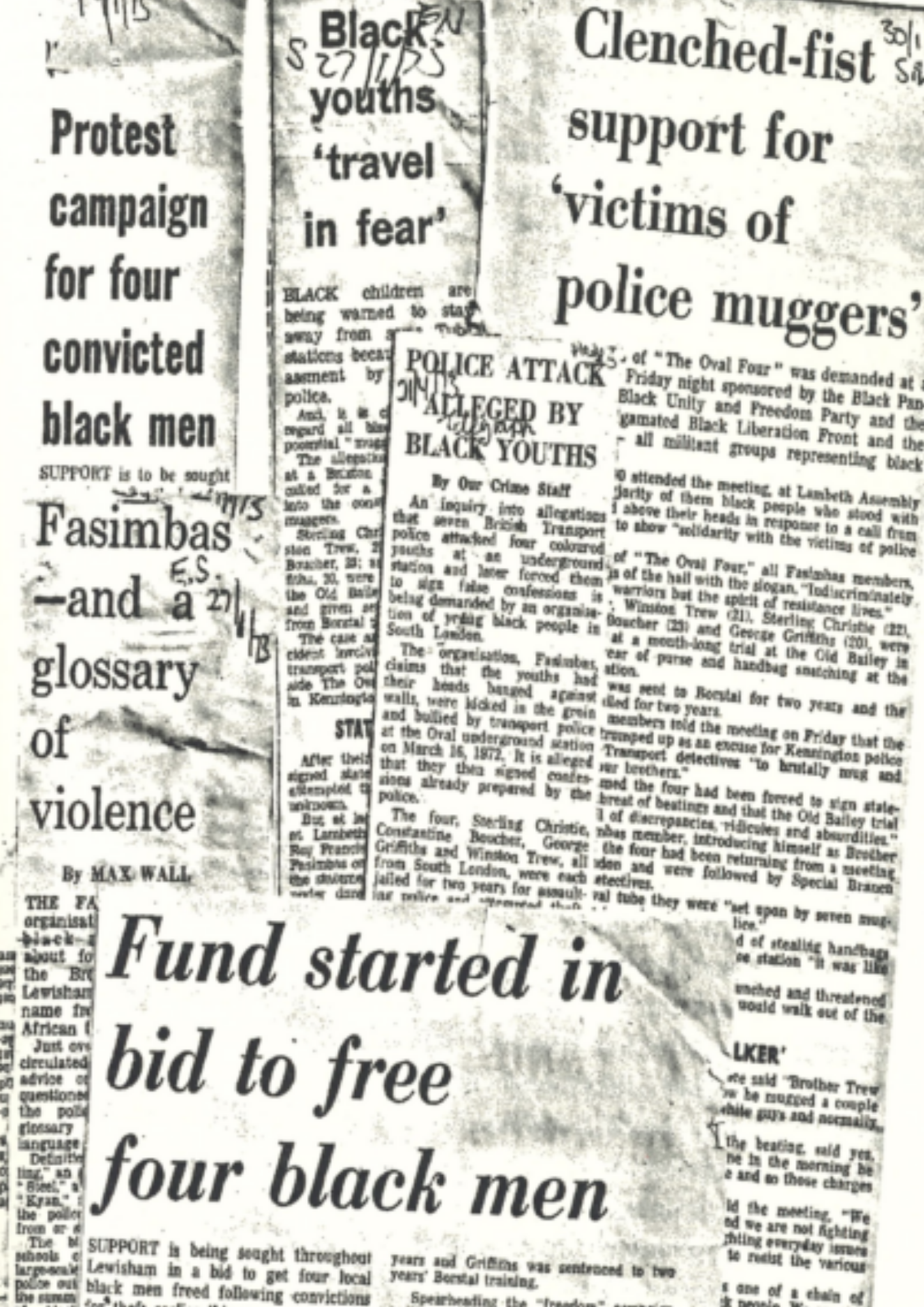

Ridgwell died in prison in 1982, after being convicted of conspiracy to steal mail bags from the railway depot he was supposed to protect, but not before he had ‘fitted up’ at least 16 young black and three white men, 12 of whom were sent to prison. Since 2018, the Court of Appeal has quashed the convictions of Stephen Simmons, the ‘Oval 4’ and three of the ‘Stockwell 6’, with another member’s, Texo Johnson, appeal is due to begin on the 23rd November. Four of Ridgewell’s other known victims have either died or cannot be traced to clear their name.

Rot At The Core is divided into two. The first half, written by Graham Satchwell gives an insider’s perspective on the culture of ‘permitted corruption’ in the BTP from the 1970s to the 1990s. The second half is a moving autobiographical account of Winston Trew’s experiences of growing up black in 1950s and 1960s Britain, the disastrous impact of encountering Derek Ridgewell at the Oval tube station in March 1972 and his later attempts to rebuild his life and seek justice.

A former Black Power activist with the Fasimbas in South London, Trew has written about his encounter with Ridgewell before, both in his fascinating 2015 book Black For A Cause … Not Just Because and more recently in an article ‘Frantz Fanon and the oval four episode: refusing colonial recognition’ in International Politics Reviews. In Rot At The Core he gives more background about his childhood experiences of British racism, initially from a white boy who wordlessly punched him the eye on his first day at primary school and later from his teachers, local white gangs and of course the police.

Finding an identity and sense of purpose in the Fasimbas, which he joined in July 1970, Winston’s commitment to the group’s ‘philosophy of self-help, self-development and education’ was brutally interrupted by his encounter with DS Ridgewell at the Oval tube station on 16 March 1972. Returning from a meeting of the Black Liberation Front with a bag of donated children’s colouring books for a supplementary school the Fasimbas ran, Trew was assaulted and choked by an undercover police officer who hadn’t identified himself, before being beaten up on the way to the police station, attacked within it and forced to sign a false confession. Trew paints a powerful picture of the intense sense of disorientation caused by being violently coerced to confess to completely fictitious crimes.

That Ridgewell could so easily target young black men on the tube to be fitted up, relied on the highly racialised nature of the crimes of ‘sus’ (being a suspected person) and ‘mugging’ (theft from the person) and that police witness evidence alone was enough to win a conviction. With Black people still twice as likely to be the target of a Section 60 stop and search and three times more likely to be arrested, this avenue for corrupt officers to target black people as an easy source of convictions is still wide open.

How Ridgewell not only got away with his corrupt behaviour, aided and abetted by fellow officers, but was protected and indeed promoted by a network of more senior policemen who never faced sanction, is clearly told by detective Graham Satchwell, who also attests to the corrupting force of racism: ‘What we can be sure of, is that once [Ridgewell] had the reputation of fitting up young black men, he would have attracted the willing involvement of racist officers and there were plenty of those.’

For, as Satchwell asserts, ‘the Steve Simmons and Winston Trew cases were not aberrations, they were simply typical victims of the many officers who were out of control, and whose crimes were covered up by bosses’ and that ‘in large cities and towns, police corruption was a part of the working practice of many’.

Ridgewell’s corruption was apparently well known to colleagues in the BTP. It was also strongly suspected by the magistrates and judge who severely criticised his evidence in the case of the Waterloo Four in February 1972 and halted the trial of the Tottenham Court Road Two in January 1973. In fact so flagrant was Ridgewell’s corruption that in 1973 the National Council for Civil Liberties (now Liberty) asked the Home Secretary to order an investigation and on 31 July 1973 an episode of BBC TV programme Cause for Concern was devoted to the improbability of his evidence.

And yet Ridgewell never faced any sanction from the British Transport Police, only changing role in 1973 to a better position at the Bricklayers Arms railway depot, where he subsequently fitted up Stephen Simmons and his two friends in 1975. And when his thieving from the Bricklayers Arms depot was eventually detected in 1978, a cursory and poorly supported investigation led to the conviction of only him and two junior colleagues.

Once Ridgewell was convicted of mail bag theft in 1980 he was swiftly written off as a bad apple now safely removed from the barrel, and there was no need to ask any tricky questions of colleagues and supervisors about how he operated corruptly for so long and certainly no need to revisit his past actions to look for any more criminality. As Ridgewell famously explained, he “just went bent”, so no further explanation was necessary. And herein lies the problem with the BTP’s apology of last week, which characterises Ridgewell’s egregious corruption and the systemic racism that enabled him as a relics of the past. It is all very well to ‘regret that we did not act sooner to end his criminalisation of British Africans, which led to the conviction of innocent people’ and lament the ‘trauma caused to the British African community by a corrupt BTP officer, whose misuse of his powers caused harm not only to the innocent young people criminalised, but also to their families and community’. But where is the promise of an inquiry into all Ridgewell’s cases to see which other people’s lives he may have ruined? Where is an inquiry into why no action was ever taken to discipline him prior to his 1978 arrest? Instead, D’Orsi proffers the hackneyed palliatives of anti-racism training, a more inclusive police force and maybe even the sponsorship of a criminology bursary for a person of African descent.

Winston Trew’s fight for justice to clear his name has taken his entire adult life. A British Transport Police force that was free from rot at the core would not have allowed him to wait so long.