Frances Webber explains why Corporate Watch’s ‘The UK border regime: a critical guide’ is an essential resource for activists.

In the overcrowded market of books on immigration control, Corporate Watch’s 331-page book, The UK border regime: a critical guide, is one which will not only be read, but will be an indispensible resource for activists. My initial doubts that yet another book on immigration could tell me anything new were quickly dispelled: it is a goldmine of basic, vital information about how the UK’s immigration control system works and to whose benefit.

In the first section, entitled ‘Background’, after a brief history (from Henry III to the Hostile Environment, including a moving graphic of the Iranians’ hunger strike in 2011) the infrastructure of control is described. All the various departments, units and commands within the Home Office immigration directorate are set out, with acronyms such as RALON (Risk and Liaison Overseas Network), NRC (National Removals Command), ISD (Interventions and Sanctions Directorate), what each does, and how they all work together – but that is just the beginning; as the authors explain, the border regime also comprises transport and security companies, local authorities, homelessness charity workers, NHS receptionists, employers, the media and the far Right..

The second and longest section describes the features of the control system, starting with the reporting system which applies to 80,000 migrants, from which officials, we learn, detain twice the number needed to reach removal targets, as half those detained will not be removable. The Home Office is seeking to make detention on reporting’ the main source of volume removals’, including same-day removals, using both fear and hope to keep migrants reporting, but with NATT (the National Absconder Tracing Team) and the Police National Computer to fall back on if they don’t . Chapters on asylum dispersal, immigration raids, detention and deportation are all packed with useful information. We are taken through the process from receiving a tip-off through a raid to the deportation, learning en route that morale is a huge problem with enforcement officials, made worse by constant rebranding, budget cuts and bullying, and not helped by rewards such as cake for the officer making the most arrests.

As we would expect from Corporate Watch, we are given a wealth of information about the contractors who profit from enforcement. Who knew that dogs and handlers used in border controls at Calais are provided by a company called Wagtail? The Calais chapter describes – and costs – the massive and hugely expensive infrastructure of walls and fences, drones and sniffers, policing and juxtaposed controls – an infrastructure responsible for the deaths of a hundred migrants in the past decade, even sniffing out a French security company linked to Calais mayor Nadia Bouchart, whose efforts to discourage migrants have extended to closing community centres as well as criminalising food distribution.

Another chapter in this section which is revelatory is ‘Hostile data’, which goes into detail on the databases the Home Office has, their links with each other and with police, HMRC and other databases, and the creation of integrated platforms, data sharing agreements and arrangements, and private sector links such as Experian, a company which sells a ‘right to work’ checking app for businesses and acts as the middleman between state and private sector needs, making money from both sides, The Mosaic profiling database, built for corporate marketing, uses Experian’s data to sort households into 67 ‘geodemographic’ categories, and is sought after by local authorities, government agencies and police to assess risks of re-offending and to help in custody decisions. The implications are terrifying, and the immigration exemption in the recent Data Protection Act means we often won’t even know about them.

The third section, ‘Consent’, recapitulates Corporate Watch’s recent report Who is immigration policy for? The media politics of the hostile environment. After a discussion of how collaboration works, based on a case study in which the Department of Health sought to convert frontline NHS staff to the practice of charging for treatment, we are taken through the ‘show of control’ that is all immigration policy can do, in the context of the electoral politics of migration, the dense ecosystem linking corporate interests, media, politicians, and the processes whereby far-right slogans become mainstream party positions through the politics of fear and the ‘anxiety engine’. The final section, How can we fight it?, draws lessons from the resistance described in each chapter, and prescribes new relations of solidarity and the finding of common cause between citizens and migrants, linking, for example, citizens fighting gentrification and social cleansing with migrants fighting raids. Two extremely useful annexes detail major Home Office immigration contracts, and profile the major companies involved in their performance.

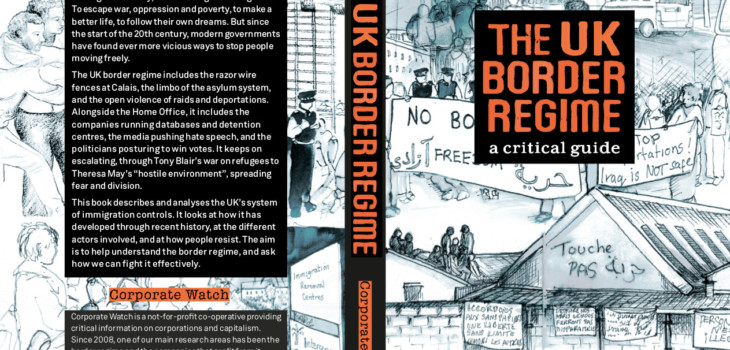

The UK border regime is eminently readable, and has many hand-drawn illustrations making it a pleasure to look at – a rare feat in books dealing with such a subject. Accessible, up to date to October 2018, and written from a grassroots, activist perspective, it is a hugely valuable resource.

Related Links

Book available from the Corporate Watch website, price £9.00.

Thank you for the review, Frances. I entirely agree about what an excellent resource this book is for political activist to focus away from the abstract debate on immigration to the concrete border regime. The graphic on ‘THE BORDER REGIME MONSTER’ page 49 is amazing.