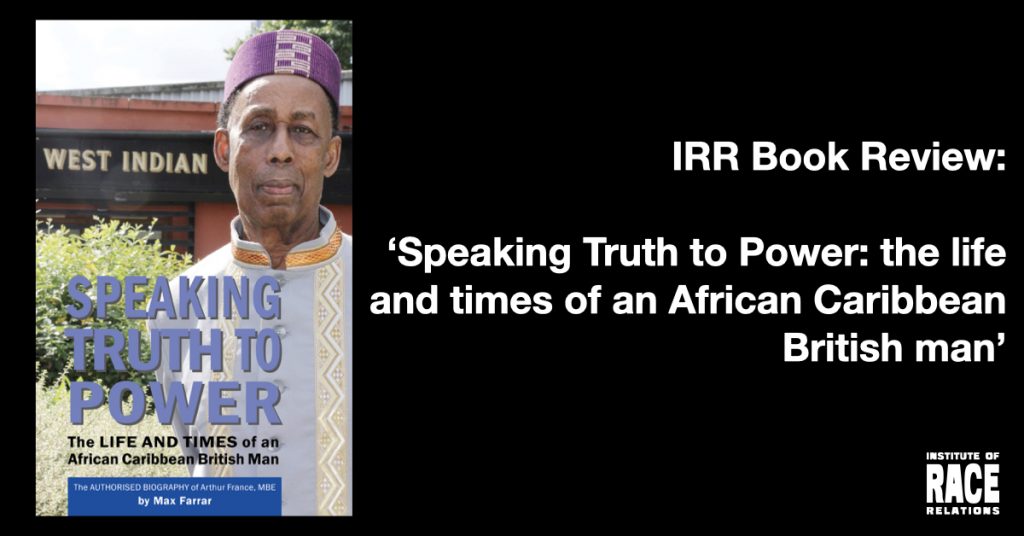

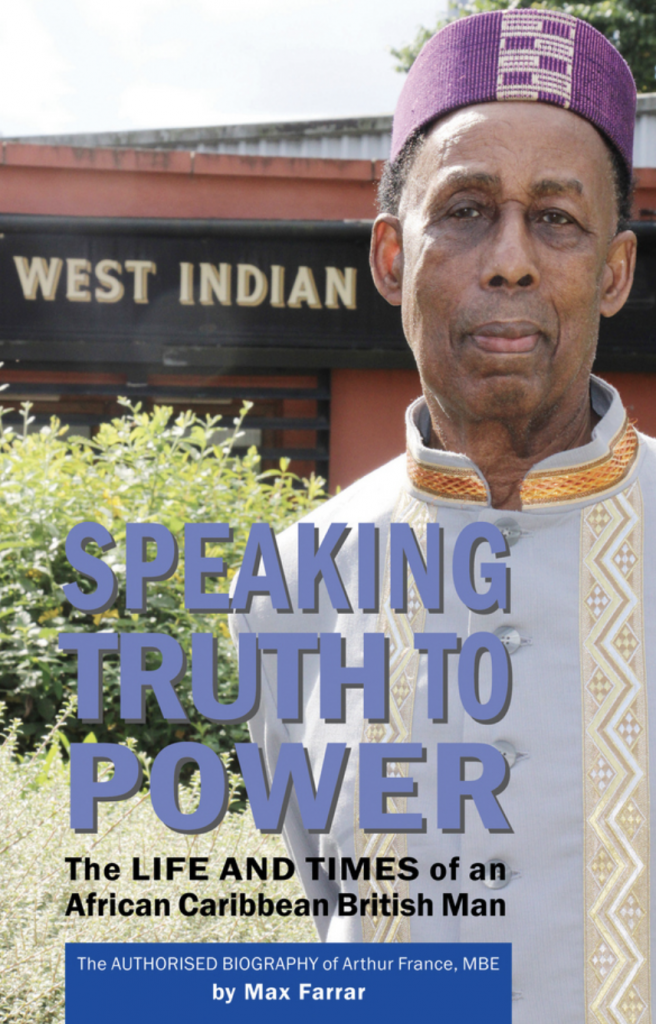

Anne-Ysore Onana-Oteba reviews the biography of Arthur France, a community activist who founded the Leeds Carnival 57 years ago.

I have heard the story of my father’s journey from Cameroon to France when he was just 18 years old many times, and with it always came his disappointment at what the promise of a bright and new future turned out to be: a challenging quest for a better life in a place that doesn’t want you. This story, despite being personal to my father, is in a way universal to many of those from previously colonised territories – those who have been sold the myth of an ideal life in the country that is responsible for many of the economic, social and political problems they often experience in their home country.

Like my father, Arthur France experienced a similar journey when leaving his home, the Caribbean Island of Nevis, and moving to Leeds in 1957. And, like my father, Arthur France had to adjust and find his way to a life in the ‘Mother Country’.

This tale of a resilient and restless life is beautifully told by Max Farrar, activist, writer and life-long friend of Arthur France, in his biographical book Speaking Truth to Power: the life and times of an African Caribbean British man. At first, I thought it odd to write a biography of someone who is still alive (Arthur France is almost 90), as it seemed to me an ominous way to pay tribute a little too soon. But my cynicism quickly disappeared in the reading. For this biography is both an homage to a friend who has accomplished so much for himself and his community, and a window on to the wider story of Afro-Caribbean descendants establishing themselves in the UK during the latter half of the twentieth century, at a time of racial unrest and racist legislation.

The book traces not only Arthur’s life story, but also highlights the roles of prominent activists, including Benjamin Zephaniah, John La Rose and Darcus Howe, in the forging of a strong and united community of people fighting against oppression and for racial justice. Along with these more widely known names are a variety of people that Arthur calls friends. Their inclusion shows how Arther’s achievements would not have been possible without collective community building.

Farrar takes us on a chronological journey through Arthur’s life, with chapters spanning from his childhood and adolescence in Nevis, his move to Leeds, his education studying building construction and professional beginnings working for British Rail, to his involvement in the Black Power movement in Leeds and creation of the Leeds Carnival in 1967 (then titled ‘Leeds West Indian Carnival’). It ends by focusing on the recent post-pandemic years, with the final chapter revolving around Arthur’s family, who have always been the driver of his political engagement and struggle for social change.

To provide some greater context, the book includes an appendix that focuses on the colonial history of Nevis and St Kitts from the Anglo-French occupation in the seventeenth century through to the twentieth, detailing the impact of slavery and colonialism on the island. This is a much more historical account, but still essential to explain some of the contexts that have shaped Arthur’s identity. The author’s choice to exclude this context from the core chapters is explained in the introduction: ‘not everyone wants to read this grim – but ultimately inspiring – chapter’ (13). The decision to leave the reader a choice to engage with the heavier side of history seems at first a missed opportunity to shed light on the reality of British history. Yet this choice does fit with the overall tone of the book: a hopeful and accessible tale of a man’s life-long achievements, and an educational resource for people who are not necessarily familiar with the history of grassroot organising in Leeds and the beginnings of Black Power movements in the UK.

Max Farrar has been active in community organising in Leeds for decades working with the David Oluwale Memorial Association, Utopia Theatre, UK Friends of Abrahams Path, and Leeds for Change.[1] But he is a white man telling the story of a Black man, and he acknowledges it. Repeatedly, he positions himself in relation to his friend, Arthur, and does not shy away from clearly stating the power dynamic in place as the person who gets to tell the story. Of course, Arthur France is heavily involved in the storytelling as the book is based on interviews that Farrar conducted in 2020, and one can almost hear Arthur’s voice in Farrar’s writing. However, it is the latter who holds the pen, and, in doing so, he also writes for a specific audience.

This book is an unpretentious attempt to raise awareness and educate white people on the insidiousness of systemic racism using sociological and historical evidence to back up personal stories. Chapter 3, ‘England: The Bad “Mother” Country’, recounts Arthur’s arrival and his struggle to build a social life. He was lucky enough to have his older sister, Elaine, already in Leeds, and therefore had a place to stay. However, the social reality for most people migrating from the Caribbean islands to the UK was that of poverty and racial discrimination, which made it extremely hard to access accommodation, let alone decent housing. This struggle is illustrated through personal accounts such as the experience of Alford Gardner, a Jamaican man who migrated to Leeds in 1948 and was denied housing everywhere he tried. Gardner eventually got together with four other West Indian men in order to buy a house of their own. Alongside these harrowing personal accounts, Farrar provides studies and research conducted on housing in Leeds during the period, like Christopher Duke’s report (published in 1970 by the Institute of Race Relations) on housing in Chapeltown, the area Arthur moved to, which shows the decaying and poor conditions of housing available to Black people.

Farrar’s choice to only write about Carnival in the last chapters of the book is perhaps a conscious effort to centre Arthur’s political work and radical activism and provide historical context for his achievements.

The creation of the United Caribbean Association (UCA)along with his friend George Archibald and later Maureen Baker, his fight against school exclusions and his involvement in setting up a Saturday Supplementary School for Black children in Chapeltown are just a few examples.

The UCA, established in 1966 and dissolved in 2010, provided education and social clubs in Leeds. This centring of the political aspects of grassroot organising is essential to better understand what drove Arthur to be so involved with his community – incremental change.

The biography of Arthur France allows readers to bear witness to a past that is still very relevant. It is a good start from which to dig into the struggles of the ‘Windrush Generation’ and understand how the politics of the 1950s and 1960s still shape Britain today.[2] In Farrar’s and France’s time a common racism meant ‘Black’ was anyone not white, and the wealth of community organising was a testament to this idea. Afro-Caribbean people were united with South Asian immigrants in a fight for racial justice. The social unrest of the ‘70s, prompted by police brutality and fascist ideologies spreading in the UK, was evidence of a need to fight back. The killing of David Oluwale in Leeds in 1969[3] at the hands of the police and the killing of Gurdip Singh Chaggar by racists in Southall in 1976 are just two of the times’ crimes. Reading Speaking Truth to Power today is a way to engage with that past and keep the memory of resistance alive.[4]

Speaking Truth to Power: the life and times of an African Caribbean British man by Max Farrar, Hansib Publications 2022.

[1] See https://www.maxfarrar.org.uk/about

[2] See https://irr.org.uk/product/the-embedding-of-state-hostility-a-background-paper-on-the-windrush-scandal/

[3] https://www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/school-of-humanities-and-social-sciences/remembering-oluwale/

[4] To go further, watch the recent Channel 4 series ‘Defiance’, which documents the British Asian community’s fight against far-right attacks in the ‘70’s and ‘Struggles for Black Community’, Colin Prescod’s four seminal films on Black communities across the UK, which give a fuller context to the fight for racial justice in the UK.