Chris Searle introduces Return to Streets of Eternity, a book of poetry by the late Guyanese writer and activist Jan Carew.

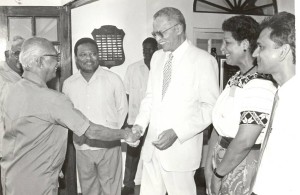

On 27 November, the life and works of Jan Carew – writer, activist and scholar – will be commemorated in London with the release of two new books. Episodes in My Life: the autobiography of Jan Carew tells the story of the multiple lives of this extraordinary writer, activist and revolutionary, godfather of Black Studies in the US, and the personal advisor to several heads of government, including Cheddi Jagan, Kwame Nkrumah and Michael Manley. Return to the Streets of Eternity brings together, for the first time, poems writted during a lifetime of passionate engagement in anti-colonial, civil rights, black power and liberation movements, including many previously unpublished tributes to nineteenth and twentieth-century revolutionary leaders and writers. Below we reproduce Chris Searle’s introduction to that collection.

Reading through Return to Streets of Eternity is like re-living the greater part of a century of struggle and for betterment in many crucial places in the world, and the moments which seized their people’s dreams and strivings. These are poems of hope and optimism, of the movement forever forward, a part of ‘the long march from breast to death’ along those streets,

Reading through Return to Streets of Eternity is like re-living the greater part of a century of struggle and for betterment in many crucial places in the world, and the moments which seized their people’s dreams and strivings. These are poems of hope and optimism, of the movement forever forward, a part of ‘the long march from breast to death’ along those streets,

and resurrection

must renew itself

with every new day

on a calendar of victory.

So within them are protagonists and heroes like Tiho the Carib, the Ghanaian slave descendants and confederates of Kwame Nkrumah, Cubans, Angolans and Jamaicans, Fedon and Bishop of Grenada, Toussaint L’Ouverture of Haiti, like the child-martyrs of Soweto, Patrice Lumumba of the Congo, Allende of Chile, Cheddi Jagan and Walter Rodney of Guyana, Claudia Jones of Trinidad, New York and London, Mumia Abu-Jamal of the USA. They are all celebrated as essential to the poet’s life and utterance, his imagination and experience, and many of them are his contemporaries, living inspirations and exemplars.

Thus Return to Streets of Eternity is poetry as a chronicle and history of the poet’s life-imagination, made, word by word, from real events transformed by images for all time, so that, as Carew writes in his ‘Requiem for Cheddi Jagan’:

the torment of the poor and despised

must be redeemed forever.

These ‘poor and despised’ are the people who are the earth of this poetry: their hopes, lives and struggles. And its words, drenched with aspiration and direction, anticipate the dawn when their freedom will be realised, when

the night of vampires must give way to day-clean,

warriors will return to long cool evenings

and the wine jars and the children

chanting poem-hymns and dancing

Carew writes many poems to his comrades of poetry, for they open up the people’s struggles to themselves and to the world beyond. Robin Dobru of Surinam, Dennis Brutus of South Africa, Agostinho Neto of Angola, Andrew Salkey of Jamaica: they are all here, all eternalised too in these avenues of words. And walking in front is another Guyanese bard, the nonpareil of Caribbean poetry, Martin Carter. There are several moments in Return to Streets of Eternity when Carew’s words could be those of Carter, so essentially Guyanese are they. ‘We do not sleep to dream, but dream to change the world’, wrote Carter in ‘Looking at Your Hands’. In his poem to Rodney called ‘The History Maker’, Carew tells us that

it’s only a dream

but when you dream with millions

the dream’s like a flower awakening

to trumpet new dawns of reality.

And remembering the March 1960 massacre of 69 protesting South Africans at Sharpeville in his poem ‘I Fight for What Must Be’, Carew writes two lines of a raw and naked imaginative beauty and power that are Carter to the core:

I fight for what must be and memories that

cling like bark to a tree.

All these humans: visionaries, activists, militants, martyrs and writers are the living flesh of Carew’s poetry and those who walk, proudly and in freedom, along his eternal thoroughfares, so that we can always seek their counsel, talk to them, walk alongside them and join in their courage, clarity, beauty and solidarity. They are, as Carew describes them, ‘the heirs of everlasting hope’ and they carry our dreams in order to give them back to us:

The dream that all peoples have a right to share

The water of the River of Life

And drink with their own cups.

Carew’s cups are for us all, and they carry the essence of continuing life, its struggles, its pleasures and its victories.

Related links

View details of the book launch on 26 November in London