Past oppressions are written into our statues, our architecture and our walls. This special issue of Race & Class brings a new perspective to reparatory history.

‘We are, at this moment, witnessing an eruption of active memory’, say Anita Rupprecht and Cathy Bergin. Resistances mobilised around Confederacy statues have provoked mass protests and fierce debate. In Baltimore 2017, statues of Stonewall Jackson and Robert Lee were carried through the streets. Following the killing of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, Virginia, anti-racist protesters in North Carolina pulled down the statue of a Confederate soldier. The ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign, calling for the removal of statues of Cecil Rhodes, drove international debate about decolonising the curriculum at Universities, which spread from South Africa to Oxford. This special issue of Race & Class 60.1, ‘The past in the present’, brings a new perspective to reparatory history, as a way of recognising the wrongs of the past, and actively working towards repair in the present. Following the reparative history conference at Brighton University last year, we reproduce three articles by Catherine Hall, Anita Rupprecht and Cathy Bergin, and John Newsinger.

‘Could re-thinking the past, taking responsibilities for its residues and legacies, be one way of challenging rightwing politics and imagining a different future?’ asks Catherine Hall. Calling for an active reparatory history that ‘brings slavery home’, she argues that only by bringing the past into the present day will we develop an understanding of Britain’s involvement in slavery, and ‘our responsibilities, as beneficiaries of the gross inequalities associated with slavery and colonialism’. Hall founded the Legacies of Slave-ownership project, which followed the material traces of the £20 million, paid by the state to British slave-holders as part of the Emancipation Act, which was funnelled into financial, industrial, cultural and political institutions in the UK. By following the ‘economic and cultural after-life of slavery’ and the ways slavery and empire have been represented into the present, the author disrupts the distance between histories confined to ‘here’ and those confined to ‘there’ in order to trace ‘the dialectic between past and present, and the local and the global’.

Rupprecht and Bergin build upon Hall’s call to open up the ‘entangled histories’ of racialised capitalism by exploring the connection between Caroline Anderson, who lived in Brighton and received money from a family plantation in Brewer’s Bay, Tortola, and an aborted slave uprising on the plantation in 1831. The Tortola conspiracy is a little acknowledged contribution to the Atlantic-wide wave of black anti-slavery rebellion and resistance, which connects ‘metropolitan accumulation in UK to everyday resistances in the Caribbean’, illuminating, as Colin Prescod says, the ‘radical history of resistance to White supremacy, locally and globally’.

Rather than silencing violent pasts with narratives of ‘closure’, the past must be brought into dialogue with contemporary racialisations. John Newsinger uncovers the suppressed histories of Britain’s involvement in some of the bloodiest repression post-1945, and takes issue with the Labour party’s ‘progressive’ reputation in imperial affairs, deriving from Atlee being seen as a liberator of colonial rule in India. Revealing how this reputation is dependent on brutal wars of repression in Malaya, Indonesia, India, Vietnam, Palestine, Kenya, Korea and Iran, Newsinger works to undo the omissions in British imperial history.

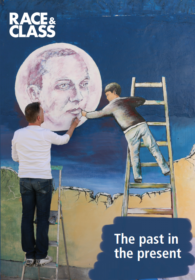

But how do we mark the past in the present when memory is silenced by political repression? Bill Rolston and Amaia Alvarez Berastegi explore how memory in Spain must be exhumed from under layers of fascist policies established by Franco’s authoritarian state from 1939-1975. ‘Franco’s victory was not simply a military one’ the authors argue, ‘but also a triumph of exclusive memory in the public sphere’. Much of the political significance of Miguel Hernández, one of Spain’s most popular poets who died in a fascist jail in 1942, has been silenced. The authors explore how ‘the authentic Miguel’ is exhumed through an annual mural painting event in Orihuela, Valencia, ‘the people are resurrecting the dream in a visual way… the dreams of Hernández and all who suffered at the hands of fascism’.

The collective mural painting event in Orihuela becomes an act of social healing, which not only remembers the dead, but ‘displays one’s remembrance in pursuit of respect, acknowledgement and inclusion’ in an overdue act of justice. Reparative history is about more than recognising how the legacies of the past live on in the present, but must actively work towards ‘hopes for reconciliation, the repair of relations damaged by historical injustice’.

Articles

- Doing reparatory history: bringing ‘race’ and slavery home by Catherine Hall

Reparative histories: tracing narratives of black resistance and white entitlement by Cathy Bergin and Anita Rupprecht - Exhuming memory: Miguel Hernández and the legacy of fascism in Spain by Bill Rolston and Amaia Alvarez Berastegi

- War, Empire and the Attlee government 1945–1951 by John Newsinger

- The next economic crisis: digital capitalism and global police state by William I. Robinson

Reviews

- The Impossible Revolution: making sense of the Syrian tragedy by Yassin Al-Haj Saleh (Sune Haugbolle)

- Race and America’s Long War by Nikhil Pal Singh (Arun Kundnani)

- Your Silence Will Not Protect You by Audre Lorde (Sophia Siddiqui)

- Deport, Deprive and Extradite: 21st century state extremism by Nisha Kapoor (Shereen Fernandez)

- Post-Soviet Racisms by Nikolay Zakharov and Ian Law (Marta Kowalewska)

- Alt-America: the rise of the radical Right in the age of Trump by David Neiwert (Liz Fekete)

Related links

I read a piece title, “The Past in the Present” and I want to make a correction where the author said ‘Heather Heyer in North Carolina,” and it should have been Charlottesville, Virginia. She (Heather Heyer) was the 32 year old lady killed when a white supremacist crash his car into a rally of protesters on the mall in Charlottesville, Virginia.

The issue of removing confederate statues is a ‘hot potato’ all over the United States especially in the south. I was in Charlottesville on Monday and I picked up a local paper and this is what going on now. They got a lawsuit aimed at keeping statues of Confererate generals Robert E Lee and Stonewall Jackson, about 7city councilors have been ordered to turn over documents related to conversations about removing the statues. The plaintiffs are asking for a paper trails, seeking emails, text messages, phone calls, memos and videos from offical city accounts. Now note city council voted 3-2 in February 2017 to have the statues removed and this lawsuit want to intervene and put a stop to the removal. If they have their way they will start another civil war to keep the statues. The black folks in Charlottesville didn’t have a say in anything when they put the statues up and that part of the problem, they feel like ‘it none of your business’ and it is our business. African Americans in Charlottesville need more inclusion right now they are basically voiceless and they tend to stay in they designated areas. We lack leadership, awareness of these issues, breakout of the mold of not wanting to hurt white folks feeling. Charlottesville black communities need a ‘Marshall Plan’ for getting ot of the ghetto blues’, joblessness blues, what’s the use in having a black mayor or if the statues are removed you still poor as hell, sick and tried of poverty…Is there enough people of color to take the city over ?

Dear Edwin S Wilson, thank you for your insightful comment. We have made an alteration in the text to make it clearer. Best wishes, Sophia

The problem with exhuming the past is that it gives rise to this question: How far into the past should we go to restore justice ? Today race relations is defined by the atrocities committed by the whites against blacks. And the reparations that are supposed to follow. But go further back and you will find that the same blacks wiped each other out in the Huttu Tutsi wars. The Arabs were the largest slave traders back then as well. Go further and we get to entire civilizations being wiped out till we reach the caves were one tribe of homo sapiens wiped out the other. Should we then go further to the point where Homo Sapiens wiped out the Neanderthal ?? I think we should look forward and make sure our current societies have equal opportunities so that all have a fair shot at life.

Dear SD,

The problem with looking forward and making sure our “current societies have equal opportunities” is that our current societies do not allow their populations to have equal footing to begin with. We cannot reasonably expect that groups who experience social, economic and political exclusion/inequalities to be able to compete with those groups who retain privilege in those categories. Of course, there are few exceptions to this reality, but that does not disregard the fact that many inequalities in society adversely affect minorities more so than dominant groups. There is no such thing as a fair shot at life for many people due to this.

Also just to clarify – the Rwandan Genocide had roots in the arbitrary grouping systems introduced by the European colonialists, who divided the country’s population in to three groups – Tutsi, Hutu and Kwa. In granting the highest-ranking positions in society to the so-called racially superior Tutsi, they sowed the seeds for the ethnic tensions that followed.