Veteran campaigner Martha Osamor talks to IRR News about her experiences in political struggles.

Martha Osamor, now 75-years-old is one of the many unsung heroes of Britain’s black community, yet she has spent almost all her life fighting to better the position of people in Tottenham and beyond – in the community, through the unions, women’s movement, local council and Labour Party (which, controversially, deselected her from standing for a safe seat in 1989). Undeterred, Martha is still fighting, most recently over the treatment of Mark Duggan’s family at the hands of the police. IRR News staff met her in a shop front rented by the African Women’s Welfare Association above Edmonton Green covered market, where she still helps to provide information and advice, to talk over her life and political times.

When did you come to the UK?

I came to the UK in 1963, three years after Nigeria became independent, to join my husband who was here to study. In the colonial days you came to study and then you went back. So I wasn’t really supposed to come at all. But when he got here, things weren’t the way we’d been told – three years became four going on six years. As a student, he didn’t have resources to do what he wanted and whatever qualification you had in the colonial country, when you came here, you had to re-do.

I had studied in Nigeria and became a teacher and he was a teacher and that was how we met. But he insisted now that I come to join him, so I set off. When I got here, I realised what he was going through. He didn’t have proper accommodation. We had one small room in Tottenham with one little like kitchen but there was no bath and the toilet was outside in the garden. And this was an improvement, he had ‘upgraded’ because I was coming. (Where he was living before, with students, the landlords divided one room up and there was a cooker on the landing and you had to pass two small rooms before you got to his room.)

We had to adjust for him to finish his course. I had to find a job and work sometimes in the night and sometime in the day and then he could go to study. And then we had the children and looked to move out of this small room to get a place and then the plan of going home meant that he had to qualify, settle and then we would join him, again. But, in between, things started changing: in Nigeria there was a military coup; then we have one child, second child, third child, fourth child. You can’t uproot your family when things aren’t settled. He did go home and we’d planned for the two big children to go and see what it was like, in ’71 or ’72. Then there was another coup, so they didn’t go. Between that September and December he had a car accident and we lost him. I’m here with four children. To go home to Nigeria, as a woman on my own with the children, after you’ve been living here, I knew would be so hard.

How did you get involved in political community activities?

Well my Dad was a lot more conscious politically than the rest of the family or the people around him. For example, he believed that every one of his children must have education, therefore we, the girls, were educated as the boys. And then he had to fight the things people were saying, ‘Why are you educating the girls?’ ‘This one is grown and should be married.’ And he was always explaining to us what was happening under colonial rule, the way the white people treated Africans, Nigerians and how they used divide and rule around tribal differences. I am from the then Mid-West now Delta State, the Ibo side of the Niger River. So I was aware then of what was happening, but not involved as such.

But being here, meant that I could see and hear what was happening. When we went to look for a bigger place to rent, there would be a sign in the window saying who they didn’t want. You are looking for a job and there’s a sign that says who they don’t want and you can see and hear that you are not wanted. All those years we saw this place as the Mother Country and thought there we will be better off, we will improve ourselves, and then go back. You never imagine that you are so not wanted; that also forms how you react and what you do about it. We lived on a council estate, in Campsbourne; and if you ever lived in a council estate in those days you could see the divisions in the things that are provided and the attitude towards you as black people on the estate. The attitude to the education of the children, immigration issues, housing – the accommodation the black people on the estate were given – you could see it was second best because we didn’t know any better. If you are living in one small room and you are given two bedrooms for you and your four children you take it. If you knew better, you would be arguing that that was overcrowding, that you wanted more space …

But, as time went by, we had to get together and talk. Those colonial divisions that we had from back home meant that when we came here somebody from the Caribbean had already been told things about you and everybody had a reason not to come together. Those from the Caribbean’s bigger islands looked down on other islands and so on. But just getting people together to talk about issues of concern meant you could bridge those gaps. So we called a meeting. When you are taking your child to school or looking for someone to mind your child when you are going to work, when you see a black person or white person who looks likely (because you can tell who wants you and who don’t) then you start to communicate about the issues – ‘come for tea’ you say and you begin to talk. It could be about overcrowding, or, if you are talking about the politics of living in a council estate, who has access to the tenants’ room. The tenants’ room was just a drinking club for the older people and the children were not welcome; we had to do something about it. For if the children were not welcomed, then they played around outside and then there’s conflict because the police will be called to control their movements.

It’s the 1970s, you are on your own, are you working as well as organising?

I taught until I had my third child, then I couldn’t do it anymore and started doing what I was doing before, working in different factories and looking after the children.

I didn’t join the Labour Party to start with, I joined the Socialist Workers’ Party because they were the ones taking up the kind of issues on the estate that we were talking about. They would bring the papers round, tell you the things that were possible, give us advice. On Campsbourne Estate there was a small piece of land and nothing built there. We wanted a tenants’ room and after-school club because children coming back from school needed somewhere and many of us were having to work. To sit down in the front room and articulate those things and then to involve the other tenants, including white tenants – some of whom don’t want black people in the estate anyway – and to help build something that black people wanted, was a struggle. We weren’t passive anymore, and so the place was built and we had our first after-school club.

We started learning how to lobby and how things worked. After we got the place, other people began to see what could be done and came to pick our brains. Gradually, we became an organisation producing things and talking to people … There was the education of our children, racism in school meant they were being suspended, excluded and sent to the ‘sin bin’ [units or schools for the supposedly educationally-subnormal]. So we have to take that on as well and there was a community centre and we would meet there every third Sunday and other people, who worked say for the council or taught or nursed who really wanted to do something about race, about women, about children and heard about the group, came to ask ‘is there anything we can do?’

Did you have a group name by then?

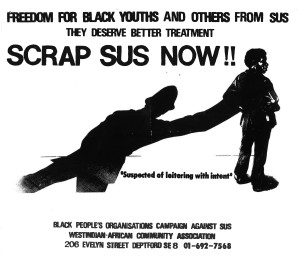

We were the United Black Women’s Action Group and, I remember, there was a squat somewhere in Euston that made a banner for us. And UBWAG became the organisation not only for us on the estate but for many others. For example, those with older children who were having a really rough time with the police came and we started looking into exactly what was happening. That’s how we bumped into the ‘Sus’ law and then we got into the campaign to repeal the Sus law [a section of the 1824 Vagrancy Act which was used to prosecute young black men before any offence had been committed, repealed in 1981]. And then we had a black pressure group in education that was just looking into exclusions We didn’t know that you could appeal if a child was excluded so people who knew would tell us what needed to be done and how you could help people prepare for those things.

Then there was a fight around the new census form [1976 sample] which included a question on ‘race’. We were doing a bit of work on housing needs and we knew that the information we were giving them in the form would not be used to help us. That’s why we were opposing the census. We said, you have to assure us that this data will be used to improve our lot. We put pressure on the council to use information on needs, the size of the family … And it worked because the council began to look at why we were located in certain estates and not by choice.

I was involved in doing these things with lots of other people of course. And in 1977 when the law centre down the road was looking for a community activist who would reach out to black tenants, I got a job in Tottenham Law Centre, which became part of the Sus campaign so all the other law centres joined in.

Was UBWAG working then with the national black women’s movement, the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD)?

Stella Dadzie [its prime organiser] lived two roads from the estate, and she was thinking, with a university group of black women interested in politics, about getting a black women’s movement together. So Stella heard about our supplementary school and she thought we should all get together to see what we were doing on the ground. The Sus law, that we were dealing with, was the issue on the Brixton side, the Deptford side, in different parts of London. We realised that what we thought was only happening to us was happening all over the place. The idea grew of linking what we were doing and making a network to be an effective force. If you are going to have a law repealed you are going to have to galvanise quite a lot of people. So that’s how we at UBWAG became part of OWAAD.

How did you come to join and be so active in the Labour Party?

I didn’t want to join the Labour Party because I felt it wasn’t strong enough in terms of defending our position [ie radical black people’s] but, like everything else, you look at who is where you want to make change and the Labour Party was winning the elections and had the councillors. In those days when local government ran the schools, everything that had to be done was by the council and it was in the hands of the Labour Party. Therefore the wise thing to do was to be part of that. It was no use speaking to one councillor about this and one about that. We had to look at how we could be effective in the labour movement and in political parties. I joined the Labour Party in ‘79 or ’80 and was working with Bernie [Grant, later leader of the council and an MP] and Norman Atkinson, our local MP, on issues like the Sus law, the police, schooling.

The Law Centre legitimised what I was doing; I was paid to do what I’d been doing without pay. And it allowed me to link that work we did in Campsbourne Estate to people who lived in different estates, including Broadwater Farm. People could see what we had done and ask can we try it? So those women who were part of the United Black Women’s Action Group who came from Broadwater Farm told us about the police. Some of their children were already in prison, some had come out. Our children were younger but theirs had real brushes with the law.

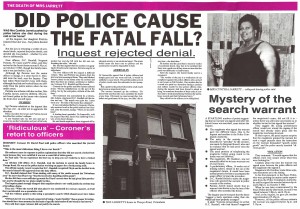

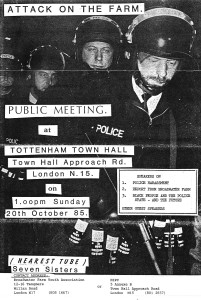

So was Broadwater Farm already central to your concerns, long before the death of Cynthia Jarrett, the riot in 1985 and the harassment and miscarriages of justice after PC Blakelock was killed?

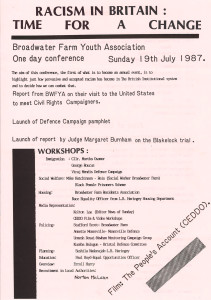

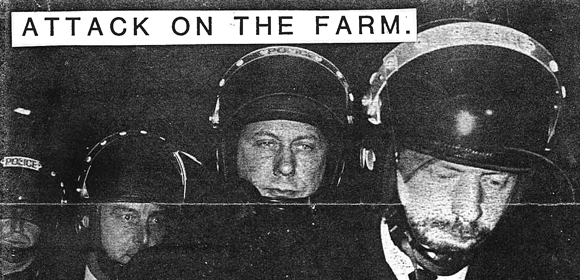

Yes. I don’t know exactly when we started in Broadwater Farm to identify who was who and having meetings in the front room like we had done . We weren’t imagining then that there was going to be the terrible backlash. [She is meaning the police operation in 1985 and the miscarriage of justice against three men convicted of the killing of PC Blakelock, and later freed on appeal.] We were just looking at what these youths that had grown up, needed. They had to be doing something and so we set up the Youth Association in 1981. We got all the youths together to say what they wanted from this estate – jobs, training, to run businesses and so on. We set up a co-op to get people together, get the council involved because by the time we started most of the places were closed as it was seen as a bad estate. Whoever was alone in the laundry or the fish shop didn’t want to run it. The grocers didn’t want to run it because they were afraid of the young people around. When we realised a big space meant for a pub in the estate was forever boarded up, we asked for it to be opened as a centre for activities: to have the enterprise downstairs, a nursery, to have a women’s centre. Downstairs, there was a tenants’ room and the constitution was changed and we encouraged people to come and participate and say these are the programmes we need, this is what we’re going to be using this place for. We wanted to get people involved in their local school, become governors of the school and to look after the elderly. Mostly, these were young black families and there was a situation where somebody would die in their home because nobody was looking after them. So the youth would cook, go to identify the elderly, bring them out. That’s the way things were moving.

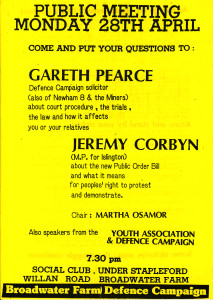

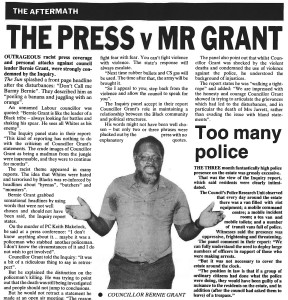

The Greater London Council, Ken Livingstone and others understood and supported and funded some of those projects later on, but they started with nothing – from just educating people to be conscious and to do what needed to be done. When we realised it was all upsetting the system, including the police, we hoped they would see the light and appreciate what we were doing. But it didn’t because after Cherry Groce was wounded in Brixton in 1981, young people were not happy because, remember, already people in Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester have connections and the understanding is that we’re not going to allow things to carry on just as they were before. [Cherry Groce’s wounding prompted the anti-police riots of 1981 which took place in over thirty cities.] So when the incident happened with Mrs Jarrett, who was killed by the police during a raid in 1985, the police reacted very badly, which we criticised. [Controversially, Bernie Grant said after the 1985 Tottenham disturbances that: ‘The youths around here believe the police were to blame for what happened on Sunday and what they got was a bloody good hiding.’] And the Labour Party, which by then I’d joined, its leadership wasn’t happy with us particularly over the international connections we were making by inviting Martin McGuinness and Bernadette Devlin from Ireland, the Black Consciousness Movement from South Africa, over Mandela linking up with Palestine, everywhere they’re hurting people we are saying ‘What are you doing to us?’ So we weren’t just an ordinary tenants’ association, we were building it as an international solidarity movement.

When did you become a Labour councillor in Haringey?

I got into the council in 1986/87 and Bernie Grant had become the leader of the council in 1985 and I was in the same ward. Then Bernie got a place in Parliament in 1987 and I became deputy leader. By that time the Black Sections [a pressure group of BME people within the Labour Party to press for more black people to be selected to stand in elections] was active. It wasn’t a conscious decision that it’s got to be black sections or white, the issue was thrown up out of the injustice we found. So when we agreed to do something like a newsletter we would also deal with abortion or gay rights because you can’t say you can free yourself when other people are not free. We thought that most of the things that we were doing were benefitting the Labour Party – we got rid of three Tory councillors on Broadwater Estate, we did not allow the National Front to meet. We would hear about a proposed secret meeting, at the Law Centre we had built a network around a phone tree: I phone my five people, you phone your 5 people. Their meeting is going to be at 6 o’clock, by quarter to six the place is full of us. So we got rid of them. And you’d think the leadership would be pleased but they were not. So we didn’t have that support when they came for us and they came with a vengeance.

You mean when you were deselected by the central Labour Party from standing for election in the Vauxhall constituency in 1989?

Yes. In Black Sections we decided that we wanted to have at least thirty black MPs (and when we say black it’s a political word – anyone who is not white). [In the 1987 general election Labour fielded twelve ‘black’ candidates of which four were elected.] So we were like a pain in their side and the leadership wanted to deal with us; so first they said we has to have something like 5,000 members for us to be officially recognised as a Section and we started battling to get members. Then they got a few members who were Asian to say they didn’t want to be called black. So they supported that and then the name had to change and there was a battle as to whether it was going to be Asian, black this and that. I was vice-chair of Black Sections then. There was a by-election because Stuart Holland, MP for Vauxhall, got elected to the European Parliament. I had eight party nominations, Kate Hoey had one. At first the Labour Executive didn’t believe that any black person would get any nominations; when I did, then they started flogging the idea that a black person couldn’t win a by-election and certainly not a person like me, who was defending people who had smashed up the Farm and all that. That is how the Labour leadership decided they were going to impose Kate Hoey on the local constituency instead of me. The rest is history.

You have always stayed very rooted to your locality, of Tottenham, in your politics compared with other people, haven’t you?

Well I think it could be that I’m not very good at moving! But it’s true. That’s all I’ve known since I’ve come to this country, I’ve lived in Tottenham or Haringey, and, besides, there’s still work to be done. Each time our building is smashed, I still have to involve myself. As I get older, I don’t do too much of the hard work because others can do that. But I think that because of the way the establishment attacks whatever is built to help ordinary working people, we need people like me around to remind others, especially young people, of the struggles – that something wasn’t given and that, if you don’t hang on to it, they take it away.

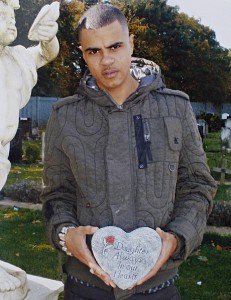

How do you feel though, say about the police shooting of Mark Duggan in 2011, when you see history repeating itself?

Like I said when I stood outside the police station that day, you know things are bad and you know a lot of bad things have happened but sometimes you just think that after all these years it can’t continue happening. Then the lies, you think to yourself how can this continue to happen? So it’s depressing you know, really, really depressing because the young man grew up on the Farm and to know that he can be shot down like that after all these years, that we can still have that kind of thing … Now you have to have inquiries, to get evidence, you have to defend but that’s how it goes. But we just hope that it’s going to get better but the way things are going … the whole of Tottenham is being gentrified so gradually prices will be so high that the young ones can’t even afford to be there and the parents can’t even afford to maintain those houses that they bought with difficulty years. We had it bad but at least we had a bit of a ladder to say OK you’re working, you’re saving, you can buy, you can get a council place, you can get transferred to a bigger place, those were our campaigns. There’s none of those things for young people to even campaign … It has to change.

Perhaps the change is when someone like your daughter, Kate, wins a seat as she just did in Edmonton, a little progress since Vauxhall?

Yes, she’s working hard, she’s got her head screwed on. Well you know they grew up on those picket lines, in this meeting and that meeting, that’s the only thing that they knew … it’s a different kind of progress isn’t it? Jeremy Corbyn was a councillor in Haringey in the ’80s and was part of our struggle. In 2015, my daughter Kate Osamor MP nominated him for leader of the Labour Party and worked hard to get other MPs to nominate him. The backlash demonising, witch-hunting of Jeremy brings back memories of what we went through.

Yes, she’s working hard, she’s got her head screwed on. Well you know they grew up on those picket lines, in this meeting and that meeting, that’s the only thing that they knew … it’s a different kind of progress isn’t it? Jeremy Corbyn was a councillor in Haringey in the ’80s and was part of our struggle. In 2015, my daughter Kate Osamor MP nominated him for leader of the Labour Party and worked hard to get other MPs to nominate him. The backlash demonising, witch-hunting of Jeremy brings back memories of what we went through.

Nice to see this stalwart highlighted here. Looks like Martha’s daughter Kate has taken over the baton – she’s supporting Jeremy Corbyn, which is a good start

By the way, Martha is one of the contributors highlighted in the ‘Look How Far We’ve Come: Commentaries On British Society And Racism?’ DVD: http://www.bit.ly/AHRBTWSCResources

Sweetie

Former SWP activist, Martha Osamor, is now headed for the House of Lords.

Her daughter has let the family and others down by allowing her son to continue as her assistant in parliament even though he has just been convicted of possession serious amounts of drugs. He was also a councilor and when discovered, resigned his cabinet seat but not, initially, his councilor position. She may not be to blame for his drugs but her continued employment of such a person brings all into disrepute. See Daily Mail 31st Oct 2018 for starters.

Wonderful to hear her story. So pleased to hear that Elder Martha is now in the House of Lords. She deserves acknowledgement of all her hard work over the years.

I don’t know why Kim has turned an article about Martha Osamor into a rant about her grandson. If the House of Commons rules allows the man to keep his job then who are we to tell anyone to sack him? Times are hard enough for young Black men. He did the crime and is serving his sentence. He does not need to be punished twice.